3UAS-konferenssi – Tulevaisuudenkestävä bisnes – osaaminen systeemeissä

Kestävä kasvu ja yrittäjyyden verkostot – osa 1

Konferenssijulkaisun muut osat:

Johtaminen tulevaisuuden toimintaympäristössä – osa 2

Tulevaisuuslukutaito ja innovaatiokyvykkyys bisneksessä – osa 3

Esipuhe: Tulevaisuudenkestävä bisnes – osaaminen systeemeissä

Etäjohtaminen, hybridijohtaminen ja teal-organisaatiot ovat nykyistä todellisuutta. Koronan jälkeen paluuta toimistoille muokataan usein yksilöiden tarpeiden mukaan. Teal-organisaatiot ovat tuoneet uutta ajattelua organisoitumiseen ja johtamishierarkiat ovat kovaa vauhtia poistumassa. Hierarkioiden poistumista vauhdittaa hyvällä itsetunnolla varustetut uudet yrittäjät ja johtajat, jotka näyttävät esimerkkiä miten homman voi myös saada toimimaan.

Osalle ihmisistä liiallinen vapaus aiheuttaa ahdistusta ja työn rajaamisen ongelmia. Osalle taas etäjohtaminen ja täysin itsenäinen työnteko sopii paremmin kuin hyvin. Usein yleispätevät linjaukset eivät toimi, ne sopivat jonkin verran kaikille, mutta erittäin hyvin eivät usein kenellekään. Esimerkiksi asiantuntijatyössä yksilölliset ratkaisut voidaan helposti keskustelemalla räätälöidä, jos näin halutaan. Räätälöinti kannattaa, sillä yksilöä tukevat tavat tehdä töitä lisäävät työtyytyväisyyttä ja parantavat työt tuottavuutta. Lisäksi erilaisia työn tekemisen tapoja sallivat organisaatiot houkuttavat erilaisia työntekijöitä, mikä rikastaa innovointia yrityksissä.

Myös tulevaisuuden ennakoinnissa on hyötyä asioiden tarkastelusta useista eri näkökulmista. Puhutaan positiivisten visioiden tärkeydestä johtamisessa ja yrittäjyydessä, mutta maailman muututtua dramaattisesti muutamassa vuodessa on tärkeää varautua myös huonoihin uutisiin. Tulevaisuuden ennakointi sisältää epävarmuuksia ja joudutaan varautumaan useisiin erilaisiin skenaarioihin. Vähintään vaihtoehdot B ja C ovat tarpeellisia. Korona, Venäjän hyökkäys Ukrainaan ja energiakriisi ovat tehneet toimintaympäristöön shokeeravan nopeita muutoksia.

Jotta tulevaisuuden ennakoinnista olisi hyötyä, tarvitaan myös toimintaa, jossa erilaisiin tulevaisuuksiin varaudutaan. Tarvitaan johtajuutta, jossa erilaiset tulevaisuudenkuvat huomioidaan ja niihin reagoidaan rohkeasti ja proaktiivisesti.

Johtamisen paradigmat muuttuvat toimintaympäristön muutosten myötä. Kuluneen vuoden konferenssissa tarkasteltiin systeemistä johtamista ja systeemiälykkyyttä, joka vastaa tämän päivän johtamisen kysymyksiin. Ensi vuoden teemana on Ratkaisuja kompleksisuuden haasteisiin, jolloin syvennytään asioiden ja ilmiöiden välisiin suhteisiin, pirullisiin ongelmiin ja erityisesti siihen, miten johtaa ja ratkaista asioita jatkuvasti yllätyksellisessä johtamismaisemassa.

Tiina Brandt, Helena Kuusisto-Ek, Sini Maunula ja Leena Unkari-Virtanen

Hand, Komulainen & Kettunen: Ennakoinnin, yhdessä tekemisen ja kehittämisen avulla kohti kestävää työelämän muutosta

- Carita Hand, Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu

- Marjatta Komulainen, Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu

- Titta-Maria Kettunen, Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu

Maailmantaloutta ravisuttavat tällä hetkellä muutokset, joilla on suoria vaikutuksia pk- yritysten menestymiseen. Ennakoidaan talouden taantumaa, liiketoimintojen pysähtymistä ja toimitusvaikeuksia. Toisaalta tällä hetkellä on vaikea ennustaa tulevaisuuden kehityssuuntia, niiden vaikutuksia Suomen talouskasvuun sekä työelämään ja siellä toimimiseen. Suomen itsenäisyyden juhlarahasto (Sitra) on vuonna 2020 kuvannut viisi megatrendiä, jotka vaikuttavat mahdollisiin tulevaisuuden näkymiin (Dufva ym., 2020):

- ekologinen jälleenrakentaminen,

- väestön ikääntyminen ja monimuotoistuminen,

- verkostomaisen vallan voimistuminen,

- teknologian sulautuminen kaikkeen sekä

- talousjärjestelmä etsii suuntaansa.

Sen lisäksi, että megatrendit muokkaavat työtä ja työn tekemisen tapoja, työelämä itsessään toimii keskeisenä muutosvoimana reilun, kestävän ja innostavan tulevaisuuden rakentamisessa (Dufva ym., 2021). Se, miten työtä tehdään nyt, vaikuttaa siihen, millaiset tulevaisuudet ovat mahdollisia (Dufva ym., 2021).

Resilienssi on kestävän menestyksen edellytys

Nykyistä liiketoimintaympäristöä kuvaa uudenlainen epävarmuus, jossa jatkuva kyky muuntautua uuteen on yritysten selviytymisen edellytys (Baran & Woznyj, 2021). Tällaisessa toimintaympäristön myllerryksessä yritysten pärjääminen ja usko tulevaisuuteen nojaavat resilienssitietoisuuteen. Resilienssi on kykyä ennakoida, ponnahtaa muutostilanteista takaisin sekä kukoistaa niiden jälkeen (Barasa ym., 2018; Riess, 2021; Vercio ym., 2021). Resilienssi rakentuu yrityksessä työskentelevien yksilöiden sekä yrityksen omien ominaisuuksien pohjalta (Vercio ym., 2021), mutta kaikista tärkeimpänä elementtinä voidaan kuitenkin nähdä vuorovaikutus, jonka avulla resilienssiominaisuudet saadaan työyhteisössä käyttöön (Rangachari ja Woods, 2020). Siksi ennakoinnin lisäksi työntekijöiden äänen kuuleminen ja tasavertainen osallistaminen yhteiseen kehittämiseen sekä työyhteisössä jaetut arvot ovat keskeisiä resilienssitietoisuuden toteutumiselle.

Resilienssi voi olla yrityksissä myös keino, jolla edistetään kilpailukykyä ja kulttuurista sopeutumista (Meriläinen & Hand, 2022). Muutostilanteissa yritys, joka kykenee alati mukauttamaan toimintaansa ja rakenteitaan, selviytyy todennäköisesti parhaiten. Se vaatii kuitenkin, että yrityksen sisällä toiminta on rakentunut itseään organisoivaksi systeemiksi, jossa ketteryys ja nopea muutoksiin reagointi ovat keskiössä. Sitä ei tue vallan ja vastuun keskittäminen organisaation ylätasolle, vaan ketteryys ja nopeus edellyttävät vastuun ja päätösvallan jakautumista ja sitä myötä koko työyhteisön itseohjautuvuutta (Larjovuori ym., 2021). Johtaminen muodostuu ja kehittyy yhteisölliseksi asiaksi.

Kestävän johtajuuden ytimessä uudet arvot ja toimintatavat

Tulevaisuuden johtamiselta vaaditaan toimintaympäristön ja toimialan ymmärrystä, muutoksen ja kehityksen edistämistä, vaikuttavuuden vartioimista ja kestävyydestä huolehtimista (Jokinen & Karhapää, n.d). Maailman muutosvoimien myötä työn tekemisen tavat, työntekijöiden arvot ja liiketoimintaympäristö muokkautuvat (Niiranen, 2020). Johtamista haastavat muutokset taloudessa, markkinoinnissa ja digitaalisessa kehityksessä. Johtaminen ei enää ole aseman perusteella syntynyttä, vaan johtajan odotetaan osoittavan hyödyllisyytensä omalla työllään ja osaamisellaan. Työntekijöiden näkökulmasta työn odotetaan vastaavan yksilöllisiin tarpeisiin, arvoihin ja päämääriin (Larjovuori ym., 2021).

Uudenlaisessa tilanteessa menestyminen edellyttää johtajalta ihmisläheisyyttä ja jatkuvaa vuorovaikutusta: avoimuutta, henkilöstön kuulemista, yhteisen päämäärän sanoittamista ja ymmärtämistä. Johtajan tulee välittää turvallisuuden tunnetta muutosten tuomissa epävarmuustilanteissa sekä toimia tasapuolisesti, oikeudenmukaisesti ja reilusti. Autoritaarisuuden sijaan odotetaan, että johtaminen on valmentavaa ja palvelevaa. Johtajalta itseltään odotetaan hyvän itsetuntemuksen lisäksi itsensä johtamisen taitoja ja empatiakykyä (Larjovuori ym., 2021).

Kilpailuetuna kyky hyödyntää henkilöstön osaamispotentiaalia

Työn murrosvaiheet synnyttävät organisaatioille osaamishaasteita. Menestyäkseen globaalissa kilpailussa organisaatioiden tulisi löytää myös kestävään kehitykseen liittyvät ydinosaamisensa. Nämä toimialasta riippumattomat ydinosaamiset integroituvat tasapainoisen, oikeudenmukaisen, ympäristöä huomioivan ja tasa-arvoisen yhteiskunnan rakentamiseen (Hand & Komulainen, 2022).

Strategisessa osaamisen johtamisessa yhdistyy strateginen johtaminen, henkilöstövoimavarojen johtaminen ja osaamisen johtaminen (Huhtalo ym., 2018). Organisaatiot pystyvät vastaamaan tulevaisuuden haasteisiin vain oppivien työntekijöiden avulla. Kilpailu työntekijöistä kiristyy, mikä tekee osaajien rekrytoinnista haasteellisempaa (Volini ym., 2019). Yritysten keskeisimmiksi kilpailueduiksi nousevatkin osaavat ihmiset, joilla on sekä monipuolista ja ajanmukaista osaamista mutta myös uudenlaista erityisosaamista (mm. IqBal ym., 2020).

Pelkällä tutkintokoulutuksella ei enää ehditä reagoida työelämän muutosvauhtiin, vaan vastuu osaamisen kehittämisestä siirtyy yhä enemmän organisaatioille ja yksilöille itselleen. Toisaalta yhä useammat ihmiset työskentelevät tulevaisuudessa yhä pidempään, mikä aiheuttaa sen, että henkilöstön ikä, osaaminen ja kokemus vaihtelevat entistä laajemmin organisaation sisällä. Se täytyy ottaa huomioon työvoiman suunnittelussa, urapoluissa ja työn joustavuudessa (Davies ym., 2011).

Yritysten resilienssiä ja kestävää työkulttuuria rakennetaan yhdessä

Resilienssin vahvistaminen ja kestävän työkulttuurin rakentaminen saattavat olla asioita, joiden merkitystä ei vielä täysin ymmärretä tai joihin liittyviä asioita on yrityksen sisäisesti hankala lähteä kehittämään. Euroopan sosiaalirahaston rahoittaman Katse tulevaisuuteen -hankkeen tarkoituksena on auttaa sosiaali-, terveys- ja hyvinvointialan alle 250 hengen mikro- ja pk-yrityksiä näiden tavoitteiden saavuttamisessa sekä antaa yrityksille konkreettisia työkaluja kestävän työkulttuurin rakentamiseksi. Samalla hanke toteuttaa Metropolian strategiassa määriteltyä tavoitetta kestävän kehityksen edistämisestä.

Hanke pohjautuu aikaisempiin ESR-hankkeisiin: Onni, Mikko ja Tuottavasti moninainen. Siinä hyödynnetään sekä aiemmissa hankkeissa kehitettyä yritysprosessin mallia (www.tyohyvinvointiboosteri.fi) että huomioidaan aikaisempien hankkeiden tuottamat tulokset, joilla on yhteyttä resilienssiin ja kestävään työhön. Näitä kestävän työn tekijöitä ovat työprosessit, roolit ja vastuut, yhdenvertainen kohtelu ja kuulluksi tuleminen, työkulttuuri, palaute, osaaminen, työn merkityksellisyys sekä viestintä ja vuorovaikutus (Rekola, 2020).

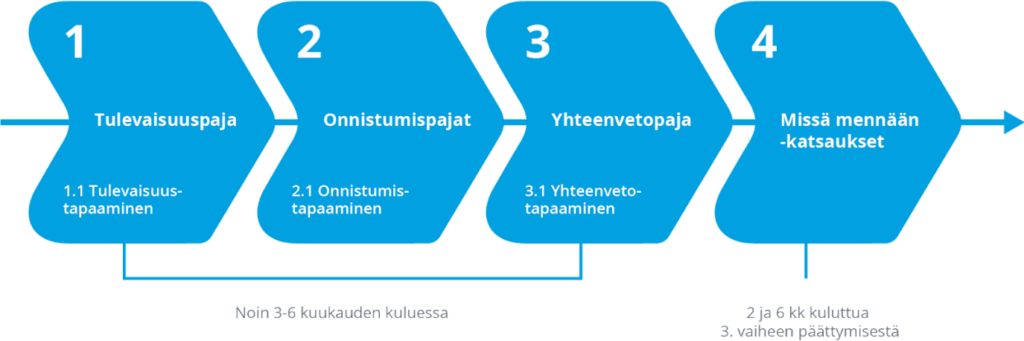

Katse tulevaisuuteen -hankkeeseen osallistuvat yritykset käyvät läpi kehittämispolun (kuva 1), jonka aikana kirkastetaan yhdessä työyhteisön tulevaisuuden visio ja rakennetaan konkreettinen suunnitelma vision saavuttamiseksi. Hankkeen aikana jokaiselle yritykselle muodostuu omanlaisensa tulevaisuuteen sanoitettu menestystarina sekä ymmärrys siihen vaadittavista teoista. Lähtökohtana kehittämistoiminnalle on kaikkien työyhteisön jäsenten tasavertainen ja aito kuuleminen ja mahdollisuus osallistua toiminnan kehittämiseen.

Tällainen työskentely mahdollistaa sen, että keskustelu ei jää siiloihin, vaan niin resilienssille kuin kestävälle työkulttuurille keskeistä dialogia käydään arjen työtilanteita kokonaisvaltaisemmin ja avoimemmin.

Yhteiskehittäminen ei kuitenkaan tarkoita vain sitä toimintaa, joka tapahtuu yhteisissä tapaamisissa, vaan olennaista on myös se, miten asioita viedään eteenpäin tapaamisten välillä, miten arvioidaan sitä, mitä on saatu aikaan ja mitä asioita pitää edelleen kehittää. Se on tavoitteellista, suunnitelmallista toimintaa, jonka eteenpäin viemisessä tarvitaan ryhmädynamiikan ymmärtämistä ja fasilitointitaitoja, joita hankkeen asiantuntijat yrityksille tarjoavat. Yhteiskehittämisen pidemmän aikavälin hyötynä on se, että uusien toimintatapojen käyttöönotto ja yhdessä sovittuihin toimintatapoihin sitoutuminen on helpompaa (Ala- Nikkola, 2019).

Katse tulevaisuuteen -hankkeen tulevaisuuspajassa visioidaan työyhteisölle toivottu tulevaisuus esimerkiksi viiden vuoden päähän. Työpajassa käytettävä tulevaisuusmuistelun menetelmä ruokkii avoimen keskusteluilmapiirin syntyä ilman, että tarvitsee ottaa kantaa siihen, miten asiat toimivat tällä hetkellä. Lisäksi jaettu visio on tunnistettu yrityksen resilienssikyvyn osatekijäksi (mm. Barasa ym., 2018; Vercio ym., 2021), minkä vuoksi sen sanoittaminen tarjoaa erinomaisen lähtökohdan yhteiskehittämiselle.

Visioinnin perusteella sovitaan tavoitteista, joita kohti rakennetaan konkreettinen polku kahdessa onnistumispajassa. Onnistumispajoissa tunnistetaan samalla yrityksen ja työntekijöiden resilienssitekijöitä ja niihin vaikuttavia asioita voimavaralähtöisesti. Yhteenvetopajassa luodaan katsaus kehittämisen aikana jo saavutettuihin tavoitteisiin ja arvioidaan, millaisia muutoksia kehittämisprosessin toteuttaminen on saanut yrityksessä aikaan. Samalla tarkastellaan yrityksen kestävän menestyksen kannalta keskeisiä tulevia kehittämistavoitteita, joita yritys lähtee hankkeen päättymisen jälkeen itsenäisesti työstämään. Parhaimmillaan kestävän kehityksen ja resilienssin vahvistamisen malli siirtyy yrityksen käyttöön pysyvästi. Lopuksi kehittämisprosessin aikana kerätystä tiedosta koostetaan yritykselle menestystarina, jossa kirjataan näkyväksi yrityksen kestävää kehitystä ja resilienssiä tukevat käytänteet sekä niiden merkitys yrityksen matkalla kohti visiotaan.

Kehittäminen on kestävää vain sen ollessa jatkuvaa

Resilienssi, megatrendit ja kestävä kehitys ovat ilmiöitä, joiden lähes jokainen yrittäjä varmasti tunnistaa vaikuttavan liiketoimintaansa. Sen sijaan ymmärrys siitä, että resilienssi ja kestävä työ eivät ole stabiileja saavutettuja ominaisuuksia vaan vuorovaikutuksessa rakentuvia ja tilannekohtaisia jatkuvasti muuttuvia menestyksen edellytyksiä, ei ole vielä täysin jalkautunut osaksi yritysten jokapäiväistä arkea. Resilienssin ja kestävän työn edellyttämä jatkuva kehittäminen saattaakin helposti typistyä heikkojen kehityskeskustelun kaltaisiksi tasaisin väliajoin tehtäviksi suoritteiksi. Tällöin kehitys ei todellisuudessa ole jatkuvaa, mikä voi jatkuvasti muuttuvassa liiketoimintaympäristössä muodostua menestyksen esteeksi.

Katse tulevaisuuteen -hanke on keväällä 2022 ollut toiminnassa vuoden. Tähän mennessä kehittämistyötä on tehty yhdessä yli 10 yrityksen kanssa, minkä lisäksi hanketiimi on keskustellut useiden muiden yritysten kanssa rekrytoidessaan osallistujia hankkeeseen. Yrittäjien ja yritysjohtajien kanssa keskusteltaessa on havaittu kahtia jakautunutta suhtautumista kehittämiseen. Osa yrityksistä suhtautuu kehittämiseen varsin positiivisesti ja on halukkaita panostamaan siihen työaikaansa, vaikka yrityksessä olisi hiljattain saatu joku isompi kehitysprosessi päätökseen. Näissä yrityksissä kehittäminen nähdään jatkuvana osana toimintaa ja toisaalta tunnistetaan se, että asioiden vieminen käytännön toiminnaksi vaatii aikaa ja keskustelua. Toinen osa yrityksistä puolestaan kertoo kokevansa, että esimerkiksi työhyvinvointi tai muutoskyvykkyys ovat yrityksessä jo niin hyvällä mallilla, ettei fasilitoidulle yhteiskehittämiselle ole tarvetta.

Johtajien ei ole helppo navigoida ristiaallokossa, jossa heiltä edellytetään yhtäältä entistä enemmän kykyä katsoa ympärilleen ja tulevaisuuteen sekä toisaalta kykyä välittää turvallisuuden tunnetta ja olla läsnä työyhteisölle. Ei olekaan ihme, että erilaiset kehittämisprojektit saattavat kiireisen arjen keskellä tuntua enemmän kuormitustekijältä kuin voimavaralta. Hankkeesta saadun palautteen perusteella yhteiskehittäminen on kuitenkin poikkeuksetta tuonut yrityksiin lisää voimavaroja. Ammattikorkeakoulut ovat merkittävässä roolissa tukemassa yritysten kehittymistä sekä muovaamassa tulevaisuuden toimintakulttuuria myös uusien työntekijöiden kouluttamisen kautta. Kysymykseksi jääkin, miten ammattikorkeakoulut voivat osaltaan vaikuttaa yritysten kehittämismyönteisyyden vahvistumiseen sekä tarjota mahdollisuuksia yksittäisiä hankkeita jatkuvammalle kehittämistuelle.

Lähteet

- Ala-Nikkola, E. 2019. Kakkutemppu osallistaen – resepti toimintamallin uudistamiseen. Julkaisussa M. Kaihovirta, A.-M. Raivio & H.-L. Palojärvi (toim.) Osallistaen. Heittäytymistarinoita fasilitoijilta. Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisuja, Oiva sarja 5, s.27–30. Helsinki.

- Baran, B. E., & Woznyj, H. M. (2020). Managing VUCA: The human dynamics of agility. Organizational dynamics, 100787. Advance online publication.

- Barasa, E., Mbau, R., & Gilson, L. (2018). What Is Resilience and How Can It Be Nurtured? A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature on Organizational Resilience. International journal of health policy and management, 7(6), 491–503.

- Davies, A., Fidler, D. & Gorbis, M. 2011. Future Work Skills 2020. Palo Alto, CA: Institute for the Future for the University of Phoenix Research Institute.

- Dufva, M. 2020. Megatrendit 2020. Sitran selvityksiä 162. Sitra, Helsinki.

- Dufva, M., Wartiovaara, Vataja, K. 2021. Työn tulevaisuudet megatrendien valossa. Sitra, Helsinki.

- Hand, C. & Komulainen, M. 2022. Osaaminen on kestävän työn perusta. Tikissä-blogi, Metropolia AMK.

- Huhtalo, T., Kangastie, H. & Konu, A. 2018. Osaamisella on väliä: Kuvaus matkalta henkilöstön osaamisen johtamiseen. B. Tutkimusraportit ja kokoomateokset 12/2018. Lapin ammattikorkeakoulu, Rovaniemi.

- Iqbal, Q., Ahmad, N. H., & Halim, H. A. (2020). How Does Sustainable Leadership Influence Sustainable Performance? Empirical Evidence From Selected ASEAN Countries. SAGE Open.

- Jokinen, L. & Karhapää, J. N.d. Tulevaisuuden työ ja elämä – näkymiä pitkän aikavälin työhön, osaamiseen ja työmarkkinoihin. Tulevaisuuden tutkimuskeskus, Turun yliopisto. Luentomuistiinpanot.

- Larjovuori, R.-L., Kinnari, I., Nieminen, H. & Heikkilä-Tammi, K. 2021. Työhyvinvointi itseohjautuvassa organisaatiossa. Avaimia kehittämiseen. Tampereen yliopiston ja Työsuojelurahaston julkaisu.

- Meriläinen, J. & Hand, C. 2022. Suhdekiemuroita – resilienssi ja kestävyys yritystoiminnassa. Tikissä-blogi, Metropolia AMK.

- Metropolian strategia 2030.

- Niiranen, H.-R. 2020. Johtajien käsityksiä osaamisen johtamisesta tulevaisuuden muuttuvassa työelämässä. Pro gradu -tutkielma. Yhteiskuntatieteiden tiedekunta, Lapin yliopisto.

- Rangachari, P., & Woods, J. L. (2020). Preserving Organizational Resilience, Patient Safety, and Staff Retention during COVID-19 Requires a Holistic Consideration of the Psychological Safety of Healthcare Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4267.

- Rekola, L. 2020. Miksi työhyvinvoinnin ja tuottavuuden kehittäminen on ylipäätään tärkeää?

- Riess, H. (2021). Institutional Resilience: The Foundation for Individual Resilience, Especially During COVID-19. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 10, 21649561211006730.

- Vercio, C., Loo, L. K., Green, M., Kim, D. I., & Beck Dallaghan, G. L. (2021). Shifting Focus from Burnout and Wellness toward Individual and Organizational Resilience. Teaching and learning in medicine, 33(5), 568–576.

- Volini, E., Schwartz, J., Roy, I., Hauptmann, M., Van Durme, Y. & Denny, B. 2019. Leading the social enterprise: Reinvent with a human focus. 2019 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends.

Ruohonen, Nykter & Saaranen: Reuse of electronic devices in enterprises: The case of closed-loop supply chain in circular economy

- Anna Ruohonen, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

- Sami Nykter, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

- Pirjo Saaranen, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

VERTAISARVIOITU / PEER-REVIEWED

Abstract

At EU level, closed-loop supply chains (CLSC) are identified as a necessary means of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. The latest developments in EU legislation and Circular Economy Strategy show that in the future producers are obliged to take more responsibility for managing the end-of-life of products.

Literature review indicates designing an optimal CLSC system maximizes value creation over the entire life cycle of a product and is vital for increasing company performance and, therefore, essential for sustainable growth. The paper focused on generating a better understanding of the businesses’ motivations, value drivers and barriers that could support or hinder closed-loop supply chain processes within organizations. By addressing these research angles, the research enlarges the body knowledge by discussing the circular economy patterns of electronic products from the perspective of businesses, which is currently underrepresented in research and overshadowed by consumer electronics.

The article is based on a 2021 quantitative survey conducted by Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences and funded by Uusimaa region (Finland), and included 404 Finnish and Baltic decision makers and executive level personnel in businesses and public organizations. Results indicate that large and micro-enterprises are more interested in electronic reusing than small and mid-sized businesses. Digitalizing business offers new opportunities, and circular economy calls for different platforms and digital solutions that connect actors such as buyers, sellers, service providers, users and intermediaries. Acquiring the necessary competences, sharing relevant product information, and building cooperation between companies are requirements for successful transition towards circular economy.

Introduction

The latest EU level developments stress the need for the reuse of electronic devices in enterprises and the transition towards closed-loop supply chain in circular economy. The EU Circular Economy Action Plan (European Commission, 2020) underlines the need to accelerate the transition towards regenerative growth model that does not deplete the planet’s natural resources. This transition to a sustainable economic system is part of the EU industrial strategy. For businesses, this means creating a framework for sustainable products and seeking to implement closed-loop supply chain-based business models as EU implements measures to reduce waste and build a well-functioning internal market for high-quality secondary raw materials.

In the context of the present research electronics and electronic devices refer, for example, to computers, mobile phones, remotes, and cameras – devices that use electric current to encode, analyse, or transmit information. With the increase of electronics and the current lack of established environmentally sustainable reuse and recycling practices, the global e-waste is on the increase (Santato & Alarco, 2022). In respect to consumer electronics alone the trend is towards shorter life cycles, and mobile phones, computers, tables, devices are replaced and disposed of at a quick pace (Tang et al., 2022). Therefore, development and implementation of efficient end-of-life solutions in respect to the electronics is central to the green transition.

In 2020 the EU commission introduced sustainability principles (European Commission, 2020, pp. 6-7) that outlined the development path for updating the legislation. The principles reflect the need to improve product durability, reusability, upgradeability and repairability, addressing the presence of hazardous chemicals in products, and increasing energy and resource efficiency. Increasing recycled content in products is highlighted along with the reduction of carbon and environmental footprint, restricting single-use and premature obsolescence and introducing the ban on the destruction of unsold durable goods. Incentives for product-as-a-service or other similar business models are encouraged. The sustainability principles also build around mobilizing the potential of digitalization of product information and rewarding products based on their sustainability performance. As a result of this work the current proposal for updating updating the EcoDesign directive extends the directive to cover very broad range of products and laying down a framework of requirements based on sustainability and circularity aspects introduced in the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (European Comission, 2022, p. 1).

The holistic view of value chain is required. The European Commission (2020) has outlined that mandatory sustainability requirements on services. Such requirements may include not only environmental but also social aspects along the value chain. Consumers shall be empowered and given more rights regarding repairing, maintenance and updating the products. Manufacturers will be obligated to provide reliable information on products at the point of sale, including information regarding product lifespan, availability of repair services, spare parts, and repair manuals. Commission will also propose that companies shall use product and organizational environmental footprint methods to substantiate their environmental claims. The directives addressing production processes, industrial certification and reporting systems shall be updated and developed.

The greater responsibility for the circular economy is placed on companies (see, e.g., Abnett & Jessop, 2021). However, for businesses the transformation to circular economy will not happen overnight. The transition requires careful planning as organizations struggle to maintain profitability along while modifying their business models. Companies are required to overcome barriers such as lack of market, inconsistent international policies, lack of finance, low consumer awareness, lack of integration that can prevent the change from occurring (Grafström & Aasma, 2021, p. 7). In their research Patel, Pujara, Kant, & Malviya (2021, pp. 4-5) identified 21 circular economy enablers, but acquiring such extensive list of organizational properties will require long-term strategic planning and development. The wide scope of new competences that organizations are to acquire and demonstrate underline the multitude of challenges that they are to tackle in the near future. Redesigning the existing linear chain to accommodate circular economy features requires multidisciplinary and holistic approach (Bressanelli, Perona, & Saccani, 2019, p. 7416).

The paper is structured in the following way. First, the literature review is introduced with the focus on the existing body on knowledge on closed-loop supply chains. The review concludes with the problem formulation for the present research. Second, the methodology employed in the research is addressed and the aspects of validity and reliability are discussed. Third, key research results are highlighted and are thereafter followed by their discussion, which is structured according to the main research angles. The paper concludes with the meaning and implication of the results, the limitations and the potential for further research and development work on the topic.

Literature review

Traditionally companies have shown very little interest in dealing with their products after they have been sold (Rogers, Rogers, & Lembke, 2010, p. 139). Generally, businesses have a forward supply chain that is a one-way flow and returning materials are seen as anomalies. EU circular economy is emphasizing closed-loop supply chain (European Commission, 2020). In circular economy the companies are expected to implement a closed-loop supply chain. A closed-loop supply chain is a system that combines the traditional forward supply chain with reverse logistics (Govindan, Soleimani, & Kannan, 2015, p. 603; Chuang, Wang, & Zhao, 2014, p. 108). A closed-loop supply chain takes back products from customers and recovers added value by reusing them entirely or partly (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 10).

Transforming an organization and moving it away from using a forward supply chain towards a closed-loop supply chain requires a paradigm shift and steering accompanied with new competences in several operational functions (Sitra, Technology Industries of Finland and Accenture, 2018, p. 33). Closed-loop supply chain management encompasses designing, controlling, and operating the system to maximize value creation over the entire life cycle of a product (Govindan, Soleimani, & Kannan, 2015, p. 603; Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 10).

Managing a closed-loop supply chain is not the activity of a single department or actor in the supply chain, but a collaboration of all relevant departments and partners (Janse, Schuur, & Brito, 2010, p. 508). In the peer-reviewed literature, the conceptual terminology varies, but the required competencies can be divided into three main categories: “network structure”, “business processes”, and “management components” (Janse, Schuur, & Brito, 2010, p. 511). These aspects serve as prerequisites for a functional and effective closed-loop supply chain. Designing an optimal closed-loop supply chain system is vital for increasing company performance (Ramezani, Bashiri, & Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, 2013, p. 825; Chuang, Wang, & Zhao, 2014, p. 118).

Implementing reverse logistics increases the system complexity and creates multiple challenges to the supply chain management (Krikke, le Blanc, & van de Velde, 2004, p. 24; Lehr;Thun;& Milling, 2013, s. 4106; Pedram, Pedram, Yusoff, & Sorooshian, 2017, p. 2). Firstly, the closed-loop supply chain consists of multiple independent actors that require coordination (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 14). Secondly, products are returned in varying conditions to the system in low volumes irregularly via multiple entry points from customers and retailers (Rogers, Lembke, & Benardino, 2013, p. 44; Rogers, Rogers, & Lembke, 2010, p. 135; Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 12). Reverse logistics has two main categories that create material flows: (1) products, and (2) product packaging (Rogers & Tibben-Lembke, 2001, p. 133; Carrasco-Gallegoa, Ponce-Cuetoa, & Dekker, 2012, p. 5585). Third category is transportation items, such as crates, containers, and pallets used in logistics (Carrasco-Gallegoa, Ponce-Cuetoa, & Dekker, 2012, p. 5585). General product return types are commercial returns, end-of-use returns, and end-of-life returns (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 11). Majority of commercial returns require only light repairs and cosmetic operations (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 11). End-of-use returns may require more extensive repairs due to extensive product usage (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 11). End-of-life returns are often technologically obsolete and worn out and recycling them back to raw materials might be the only reasonable option (Guide & Wassenhove, 2009, p. 11). A closed-loop supply chain includes irregularities and uncertainties that are important to recognize and understand when redesigning circular economy supply chain.

In the problem development for the present research the following aspects were considered. The most important parameter to gain profit from a returned high-tech product traveling through a closed-loop supply chain system is speed as the value decreases over time (Tibben‐Lembke & Rogers, 2002, p. 278). To gain the maximum available profit from end-of-use equipment in the possession of a business the recovery of the equipment must be made as quickly and as efficiently as possible.

In order to achieve this aim, better understanding of the value of and the motivations for used electronics equipment for businesses is needed as well as of the barriers that hinder circulating the used electronics equipment in closed-loop supply chains. Thus, this paper aims to answer the following questions:

- What value end-of-use electronics equipment represents to businesses?

- What barriers hinder the circular economy of the end-of-use electronics equipment?

Addressing the above facets enlarges the body of literature on the current topic and enriches the research and practice of factors impacting closed-loop supply chain formation in businesses. The research addresses the circular economy patterns of electronic products from the perspective of businesses, which is currently underrepresented in research and overshadowed by consumer electronics.

Methodology

The results of this article are based on quantitative research data. The work has been supported with funding from the Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Council (Finland). The research question was: How can the reuse and recycling of used electronic devices be made more efficient in companies? The objectives of the survey was to define product segments, business needs (what goods companies have and coming into circulation / on the other hand what products companies are looking for) and a need for a digital marketplace. This article was an overview of the main research question excluding the marketplace variables. The survey was conducted in two stages. First, 14,422 Finnish organizations received the survey on the June 15, 2021. Second, 1,090 Baltic organizations were included on July 5, 2021. The Baltics were seen as a potential expansion area for the marketplace under development. Reminder messages were sent on the June 22 and August 4, 2021. A total of 404 responses were received, resulting in the response rate of 2.6 percent.

The contact information of the respondents was collected from the company database of Selector with the following parameters:

- Finnish companies with 1-49 employees, including CEOs of the following industries: electronics and equipment manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers and recycling companies.

- Finnish companies with 50+ employees, including CEOs and Marketing, IT, Sales, Purchasing, Production, Product Development and Communications Managers from all industries.

- Baltic companies with more than 5 employees, turnover more than 50 MEUR, management level of the industries: manufacture of electronic equipment and components, waste management and recycling, storage, other logistics, film, sound, video, radio and TV program production, communications and satellite communications, computer network services and repair services.

Webropol survey platform was used as a tool for creating and distributing the survey. The questionnaire included one-option and multiple-choice questions. The perceptions on electronics recycling and reuse were measured with the five-point Likert scales ranging from fully disagree to fully agree as well as from very little to a lot; with the sixth option “I don’t know”.

The SPSS software package was used to statistical analyses. In addition to descriptive statistics, the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis and Mann Whitney U tests were used to test the difference in Likert scaled variables between two or more groups. Furthermore, Spearman’s rank correlations test the significance correlations between ordinal variables.

Profile of the respondents

The respondents were mostly top-level managers of their organization (57 %) followed by a notable proportion of middle-level managers (25 %). Most of the organizations (97 %) operated in Finland; one-third (33 %) in other EU countries and one-fifth (20 %) outside the EU. Nearly half (47 %) was medium-sized companies with the personnel between 50 and 249. Large companies represented one-third (34 %) of the respondents.

About three quarters (76 %) represented companies while one-fifth (22 %) were public administration organizations. The public organizations represented municipality, state or congregation services. In their operations, the companies focused on production (29 %), service (21 %), retail or wholesale (15 %); education, consulting or research and development (12 %).

All organizations used IT, computing and mobile devices. Other commonly used devices included entertainment electronics, such as TV (77 %), security equipment (73 %), household appliances (69 %), including washing machines, dishwashers; measurement and testing equipment (64 %), other professional electronics (62 %), media production equipment, such as audio-video production equipment (51 %). About one-fifth (22 %) also manufactured or sold electronics devices.

Validity and reliability

There was a clear correlation between the results and the initial aims, supporting the fact that the measurements were correct. Further adding to the validity, the investigation is supported by literary discussion and drawing parallels to previous research and recognizable trends.

Despite the fact that the response rate was 2.6 %, the overall number of respondents 404 was convincing and representative with all respondents’ organizations employing a spectrum of electronics. Big companies are somewhat overrepresented, but on the other hand big companies also have more weight in electronics recycling. Reliability is supported to the extent that the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. The techniques used in the analysis were employed to checking the consistency of results across parts of the survey itself. The internal consistency of the Likert scaled packages described in this report are quite high (Cronbach’s Alphas were .83 – .87).

Results

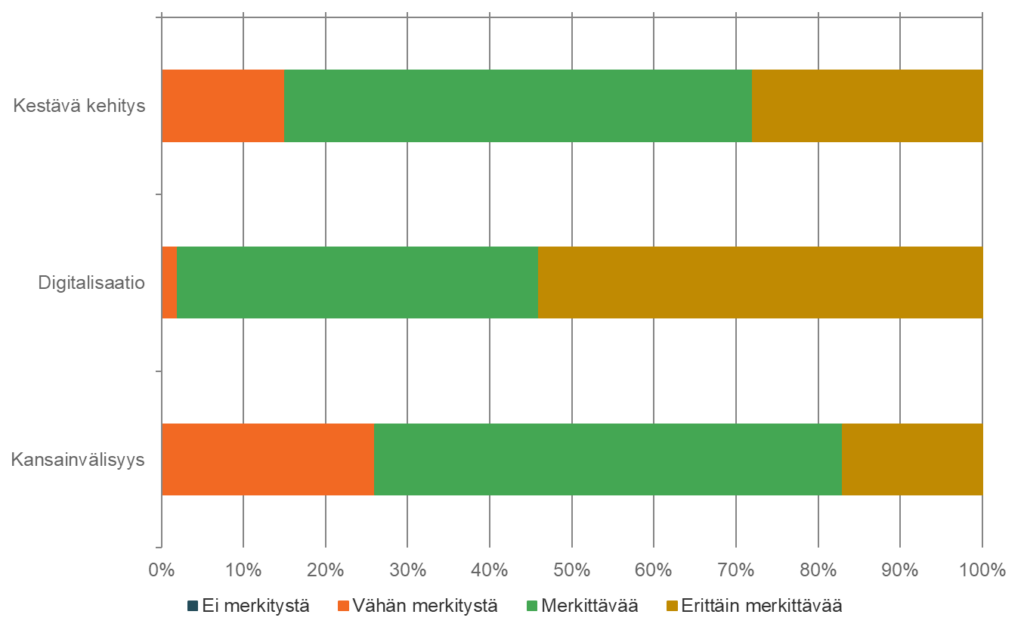

Respondents demonstrated a positive perception of the present recycling practices within their organizations (Figure 1) and found that that recycling is already part of their daily routine (80 %) and will continue to be that in the future (88 %).

The circular economy was seen as an important element in brand building, with 62 % of the respondents supportive of the view. More than half (55 %) thought that taking the circular economy into account would have a positive effect on their organization’s turnover. The larger the company, the more significant role the circular economy plays in brand building and part of everyday life and routines in the future (p=.030; p=.045). Representatives of companies, especially retail and wholesale companies, estimate that taking into account the circular economy affects more positively on turnover compared to respondents of the public administration (p=.013).

Figure 1. Respondents’ views on circular economy as part of business considerations (n = 402).

Nonetheless, the previously mentioned positive predisposition towards circular economy was not reflected in essential practical measures taken by business to advance the circular economy practices, such as the disposal amount and the estimated reuse value of the used electronics.

Figure 2. The procedures for handling customer and warranty returns (n = 90)

Figure 2 demonstrated a wide range of practices related to how customer and warranty returns are handled. If the company manufactured or sold electronic equipment, more than one-third (36 %) of the companies destroyed the customer or warranty returns. The majority of the respondents indicated that returned goods are being recycled back to raw materials (56 %) and close to half of the respondents stated that their companies are repairing and selling returned products again (49 %).

Figure 3. Value implications of the used electronics for businesses

Furthermore, almost one-third (31 %) of the respondents believed that used electronics had no value for their organization. The value of used electronics (reuse, brand, spare part, raw material or monetary value) was regarded quite low (Figure 3).

Slightly over one-third (36 %) was motivated to participate in research and development projects with universities with the aim to create and introduce better and more durable products to the market. Public administration, the large and the micro companies were more interested in development cooperation than small and medium sized companies (p=.029; p=.002). The more there was willingness to co-develop with universities the more positive were the perceived monetary, brand and reuse value of the used electronics (r=.3). In addition, the interest in maintaining one’s know-how in matters related to electronics recycling correlates positively with the interest in development cooperation (r=.3).

There were several reasons for the organizations not to engage in circulating electronics equipment (Figure 4). The primary obstacle was the difficulty to find buyers for used electronics (63 %), followed by the notion that there are too few facilities that take used electronics (49 %). Difficulties in finding information (36 %) and the poor availability of recycling services locally (34 %) were notable contributing factors as well.

Figure 4. The hindrance factors of the electronics reuse

One-fifth (20 %) found that recycling was too expensive. 12 % of the respondents noted that their corporate culture did not support electronics recycling, while one-fifth (21 %) of the respondents from public administration regarded the corporate culture as a hindrance (p=.05). The size of the organization did not affect the perceived hindrance factors.

Discussion

The research has demonstrated a wide range of practices related to how customer and warranty returns are handled. About half of the businesses repaired and resold the returned electronic equipment and/or recycled it back to raw materials. At the same time more than one-third of the companies are destroying customer or warranty returns. This leaves notable potential for further development of electronic reuse and closed-loop supply chain practices. The following discussed motivations and barriers for businesses shed light on how to support these processes.

Businesses’ motivations for end-of-use electronics equipment

The efficient work of a closed-loop supply chain and the speedy, value-preserving recovery of the equipment that is essential to it (Tibben‐Lembke & Rogers, 2002, p. 278), are subject to the businesses’ perceptions of value of the electronic products’ reuse and the related obstacles.

The research showed that in contrast with businesses’ own positive perceptions of their circular economy contributions, the reality was different and was not effectively or at large translated into meaningful practical measures that could be taken towards the closed-loop supply chain development. However, it was a promising finding that the business did see circular economy practices strongly related to their current and future practices and the daily routine operations.

Similarly, especially retail and wholesale companies found that placing an emphasis on advancing the circular economy practices within their organizations would positively correlate with their turnover. Overall, over half of the respondents expected positive connection between circular economy’s role and their organizations’ turnover. This aspect, however, contrasted with responses received among the public administration representatives, leading to the conclusion that differing motivators must be prevalent depending on the public – private operational context.

Management research and practice demonstrate a growing and ongoing interest of the relations of sustainability practices to branding (Epure & Manea-Tonis, 2017). The present research supports the connection, and the majority of the respondents viewed the circular economy as an important element in brand building. Furthermore, the company size played a role, and for the larger companies the anticipated brand impact was more significant.

The proactive approach to circular economy practices may be demonstrated by businesses’ readiness to engage in respective research and development. The present research indicated that only about a third of organizations were ready to participate in the development of better and more durable products. Among these, public administration, the large and the micro companies prevailed. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) showed low interest for research and development cooperation in the area, which is notable considering that SMEs form the backbone of Europe’s economy and represent 99% of all businesses in the European Union. This further indicated the need to reach this category of business and to support their engagement in electronics reuse processes. Based on the research results and the responses from the organizations that were willing to take active part in research development several notions arise. First and foremost, the willingness to co-develop correlated with the more positive perceptions of monetary, brand and reuse value of the used electronics. This implies that flashing out and advancing these benefits at the SMEs interface is likely to prove beneficial. Furthermore, the interest in maintaining one’s know-how in matters related to electronics recycling correlates positively with the interest in development cooperation. This, in turn, is a strong call for continued learning, advancing the understanding of concrete business practices related to electronics recycling, closed-loop supply chains and green transition.

Barriers to circular economy practices of the end-of-use electronics equipment

Similar to a plethora of motivating and value-adding factors for end-of-use electronic equipment practices, there was a number of tangible obstacles hindering the progress. Finding buyers for used electronics was the primary challenge faced by the companies, which may be interpreted as the need for enhanced cooperation and matchmaking. Other concrete challenges related to the difficulties in finding information, the availability of recycling services, the understanding that only few facilities take used electronics for processing – or perhaps the lack of knowledge of such.

These barriers were further escalated by the fact that recycling was in places perceived as too expensive, and with some companies not seeing business value in it overall.

While there is no universal solution for these challenges, the research uncovers the greater need for cooperation, matchmaking, exchange of information, products and services. Reflecting on the current trends for business process digitalization, digital platforms are likely to be a part of a solution. Digitalising business offers new opportunities, and the circular economy needs different platforms and digital solutions that connect actors such as buyers, sellers, service providers, users and intermediaries (Nikina-Ruohonen et al., 2021). The strategy outlined by European Union indicates that digital technologies needed for the green transition shall be promoted for wider adoption. The policies further support the extended producer responsibilities and incentives for sharing information and good practices. Within the field of consumer electronics, the trend is already strong and digital platforms for electronic device recycling are an integral part of the reCommerce movement (Tang & Chen, 2022). However, the respective opportunities for digital connectivity for electronics reuse for businesses is still in its infancy. The current research and the needs described by the businesses point towards this untapped potential.

Conclusion

The research focused on the reuse of electronic devices in enterprises. The main aspiration was to generate a better understanding of the businesses’ motivations, value drivers and barriers that could support or hinder closed-loop supply chain processes within organizations. By addressing these research angles, the authors contributed to enlarging the body knowledge by discussing the circular economy patterns of electronic products from the perspective of businesses, which is currently underrepresented in research and overshadowed by consumer electronics.

A quantitative survey of 404 businesses in Finland and Baltic countries showed that the positive correlations are likely to emerge at the intersections of circular economy practices implemented by companies and company turnover and brand image. At the same time, there is an indication that companies’ own perceptions of their circular economy contributions are not aligned with the more modest practical measures implemented towards the closed-loop supply chain development. The challenges pinpointed by the businesses in relation to electronics reuse pointed towards the need for greater cooperation, matchmaking of buyers and sellers of reused electronics, opportunities for exchange of information, products and services.

The implications of the research include the need for active support for businesses in their engagement in electronics reuse processes, which was especially notable in case of SMEs that form a large majority of all European businesses. The research results were translated into business and management value by employing it as basis for creating and piloting Circular Economy Digital Marketplace – CEDIM in 2022. The research offers meaningful outputs for the educational sector. First, there is a demand and readiness from the business side to engage in joint research and development activities with universities in order to advance smarter and better products and services to the market – aligned with the principles of green transition. Second, the research showed the importance of maintaining one’s know-how in matters related to electronics recycling, and the continuous learning is the key to advancing the knowledge of business practices related to electronics recycling, closed-loop supply chains and green transition.

The research was limited to Finland and Baltic countries, and extending the future research efforts to other geography is recommended, especially within European Union, where the currency of the topic is highlighted through the ongoing policy work. The present research centred on the quantitative methodology and future qualitative investigation into opportunities arising from the research in encouraged, such as advancing the knowledge of the type of continued learning that is needed and understanding the parameters and opportunities related to the creation of digital platform solutions for reuse of electronics by businesses. Ideally, and as the topic remains highly current, further research work would be aligned with corresponsive development efforts. Increasing circular economy expertise, creating better access to knowledge and information, and enhancing cooperation between companies will be key success factors in the transition of businesses towards greener processes and more sustainable future.

References

- Abnett, K. ja Jessop, S. (2021). EU broadens rules on sustainability data to capture more companies. Reuters. Published: April 21, 2021. Visited: March 6, 2022.

- Bressanelli, G., Perona, M., & Saccani, N. (2019). Challenges in supply chain redesign for the Circular Economy: a literature review and a multiple case study. International Journal of Production Research, 57(23), 7395-7422.

- Carrasco-Gallegoa, R., Ponce-Cuetoa, E., & Dekker, R. (2012). Closed-loop supply chains of reusable articles: a typology grounded on case studies. International Journal of Production Research, 50(19), 5582–5596.

- Chuang, C.-H., Wang, C. X., & Zhao, Y. (2014). Closed-loop supply chain models for a high-tech product under alternative reverse channel and collection cost structures. International Journal Production Economics, 156, 108-123.

- Epure, M., & Manea-Țoniș, R. (2017). Branding and Leadership in the context of Circular Economy. Procedia of Economics and Business Administration, 163-172.

- European Comission (2022). Proposal for a Regulation establishing a framework for setting ecodesign requirements for sustainable products and repealing Directive 2009/125/EC. (D.-G. f. Environment, Ed.) Retrieved On June 15, 2022.

- European Commission (2020). Circular Economy Action Plan. European Union.

- Govindan, K., Soleimani, H., & Kannan, D. (2015). Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 240, 603–626.

- Grafström, J., & Aasma, S. (2021). Breaking circular economy barriers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 1-12.

- Guide, V. D., & Wassenhove, L. N. (2009). The Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research. Operations Research, 57(1), 10-18. doi:10.1287/opre.1080.0628

- Janse, B., Schuur, P., & Brito, M. P. (2010). A reverse logistics diagnostic tool: the case of the consumer electronics industry. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technololy, 47, 495–513. doi:10.1007/s00170-009-2333-z

- Krikke, H., le Blanc, I., & van de Velde, S. (2004). Product Modularity and the Design of Closed-Loop Supply Chains. California Management Review, 46(2), 23-39. doi:10.2307/41166208

- Lehr, C. B.;Thun, J.-H.;& Milling, P. M. (2013). From waste to value – a system dynamics model for strategic decision-making in closed-loop supply chains. International Journal of Production Research, 51(13), 4105–4116.

- Nikina-Ruohonen, A., Nykter, S. & Saaranen, P. (2021). Elektroniikan kierratyksestä brändiarvoa. Kiertotalouden erikoislehti ”Uusiouutiset”, 7/2021.

- Patel, M. M., Pujara, A. A., Kant, R., & Malviya, R. K. (2021). Assessment of circular economy enablers: Hybrid ISM and fuzzy MICMAC approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 1-16.

- Pedram, A., Pedram, P., Yusoff, N. B., & Sorooshian, S. (2017, April 6). Development of close-loop supply chain network in terms of corporate social responsibility. Plos One, 12(4).

- Ramezani, M., Bashiri, M., & Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. (2013). A robust design for a closed-loop supply chain network under an uncertain environment. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 66(5-8), 825-843. doi:10.1007/s00170-012-4369-8

- Rogers, D. S., & Tibben-Lembke, R. (2001). An examination of reverse logistics practices. Journal of Business Logistics, 22(2), 129-148.

- Rogers, D. S., Lembke, R., & Benardino, J. (2013, May/June). Reverse Logistics: A New Core Competency. Supply Chain Management Review, 40-47.

- Rogers, D. S., Rogers, Z. S., & Lembke, R. (2010). Creating Value Through Product Stewardship and take-back. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 1(2), 133-160. doi:10.1108/20408021011089211

- Santato, C., & Alarco, P.-J. (2022). The Global Challenge of Electronics: Managing the Present and Preparing the Future. Advanced Materials Technologies, 7(2), 2101265.

- Sitra, Technology Industries of Finland and Accenture. (2018). Circular economy business models for the manufacturing industry. Helsinki: Sitra, Technology Industries of Finland and Accenture.

- Tang, Z., & Chen, L. (2022). Understanding seller resistance to digital device recycling platform: An innovation resistance perspective. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 51, 101114.

- Tang, Z., Zhou, Z., & Warkentin, M. (2022). A Contextualized Comprehensive Action Determination Model for Predicting Consumer Electronics Recommerce Platform Usage: A Sequential Mixed-Methods Approach. Information & Management, 59(3), 103617.

- Tibben‐Lembke, R. S., & Rogers, D. S. (2002). Differences between forward and reverse logistics in a retail environment. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 7(5), 271-282.

Pitkäjärvi & Rauhala: SDGs – How to arise awareness of them in business with education?

- Marianne Pitkäjärvi, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences

- Mariitta Rauhala, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

VERTAISARVIOITU / PEER-REVIEWED

Introduction

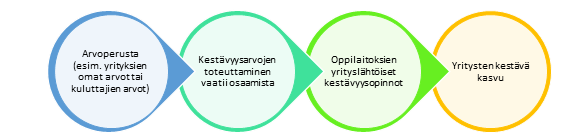

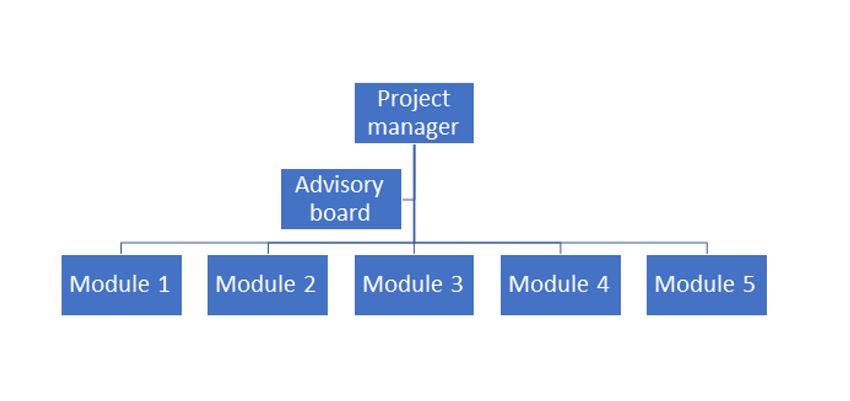

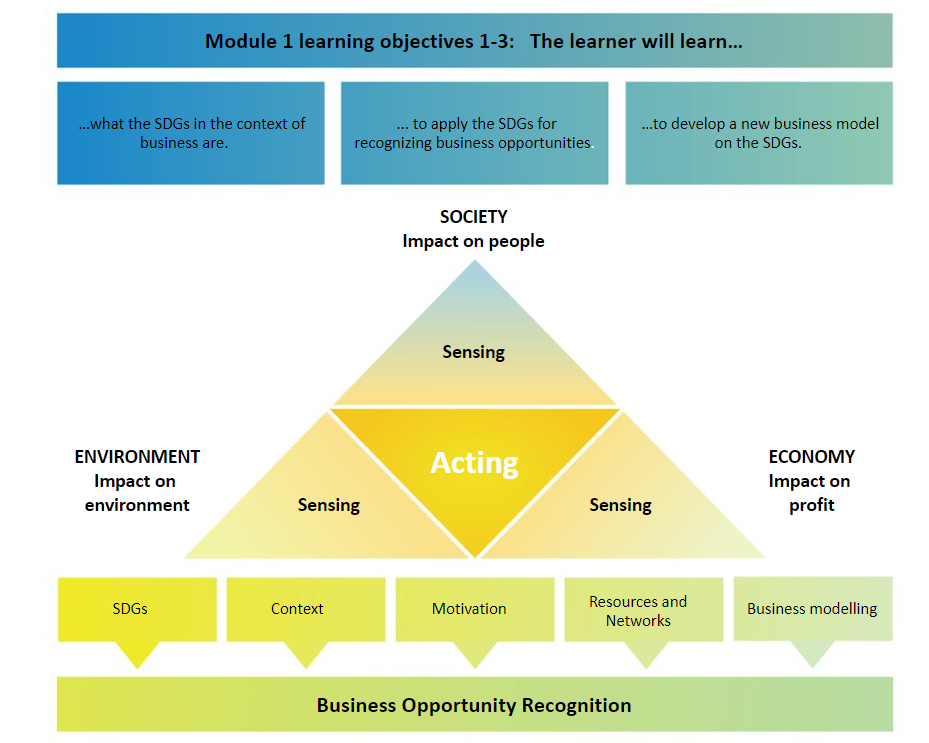

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, are a call for action to address a series of global challenges, such as environmental degradation, poverty and climate. In order to achieve these goals, it is very important that companies integrate sustainability into their business strategies. European, international project ”Knowledge Alliance for Business Opportunities in SDGs (SDG4BIZ)” creates, tests and disseminates a curriculum and training material on recognizing and realizing the business opportunities in SDGs. The planned training covers 5 modules: 1) shared value business opportunity recognition and after that selected specific opportunities in 2) food and agriculture, 3) cities, 4) energy and materials and 5) health and wellbeing.

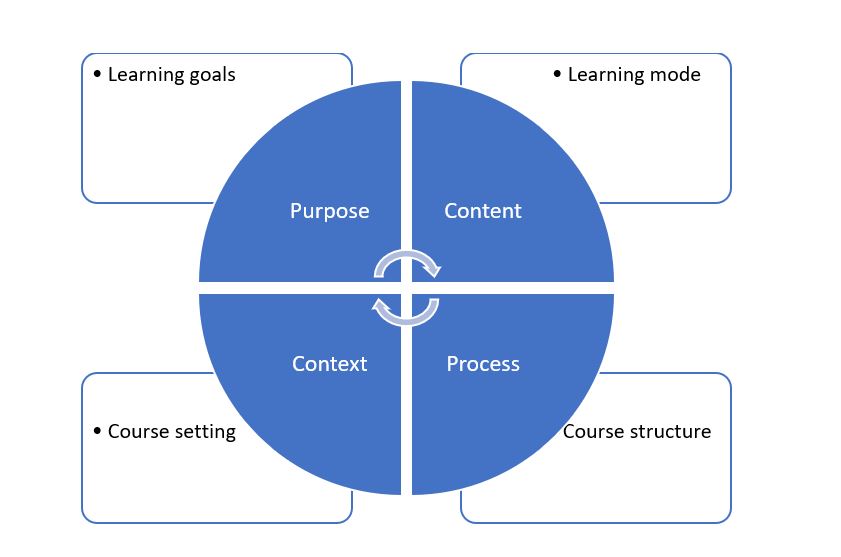

The target groups of the training are teachers, business owners and employers. This blog paper describes how the different educational needs of the target groups have been researched in the project when we have designed the first module (business opportunity recognition). Potential learners are from different countries and different operating environments. Demographic, legal and cultural factors vary widely across Europe and it is therefore important to understand the needs, aspirations and motivations of participants before designing the training.

Why service design approach?

Service design helps organizations, in this case learning designers, to see their training services from a customer perspective. Service design is based on design thinking, and it brings a creative, human-centered process to service improvement and designing new services (Stickdorn et al. 2018). Knowing the target groups and the end users is the cornerstone of service design, and the process of service design always starts with gathering customer understanding (emphatizing) (Marstio et al. 2021). In the design of learning, this means that we know our learners’ motivations, inspirations, expectations and ways of learning.

Approaching the potential end users

In this project, the potential end users of the curriculum and the training material will be trainers, entrepreneurs and employees. Prior to the creation of the curriculum and the training material, to understand the potential learners’ needs, an interview guide was designed and pilot tested. Aligned with the project plan, the interview guide addressed the interviewees’ perception of recognition of business opportunities, of development of business solutions, and of sustainable development. Furthermore, the interviewees’ preferences regarding the development of their professional competences as well as their underlying motivations to participate in an online training were explored. The key findings were documented on a user-need template Designed by Futurice, because it promotes focusing in on the essential message delivered by the interviewee.

Altogether 37 interviews were conducted by 8 interviewers from the project group. The participants were handpicked from the project group members’ own network of business people and educators. Such an arrangement was effective in the sense that it allowed for inclusion of many participants in a relatively short period of time. There was also a downside to this, however, as the material was not uniform but uneven, instead. Consequently, the results were condensed.

All interviews were conducted in Finland. Due to the prevailing COVID19-pandemic, the interviews were mostly conducted by using digital tools such, such as Teams or Zoom. The interviews lasted for 20-60 minutes. They were not recorded. Instead, the interviewer made notes and summarized them on the user-need template. Anonymity of the interviewees was assured at all phases of the data collection and handling.

To analyze the data, the Personas-template (Stickdorn & al. 2018) was used as a framework, as this facilitated adherence to the specific needs of the three different subgroups of potential learners. Whilst the data were collected and analyzed by the Finnish project group members, comments and insights regarding the Personas were gathered from the project group members in other countries.

Key takeaways

Regardless of the industry sector, the environmental element of sustainability seems to be prominent in the business people’s mind. The social aspect of sustainability, however, seems to be easily forgotten by all parties. Wellbeing at work was brought up only by some employees. In food industry as well as in nature tourism, both educators and business people identified the necessity of adhering to the three elements of sustainable development. It is perceived as an important and integral part of the company brand, a manifestation of the company values. The educators placed emphasis on the holistic approach towards sustainability, that is, the need to cover all three pilars of sustainable development in a well-balanced way. Many interviewees pointed out that this is an expectation of the customers, in particular.

When it comes to the potential learners’ expectations regarding the pedagogical approach of the course, the views were unanimous. In order to be attractive, the course needs to consist of digestible chunks, which are easily accessible and quick to complete. The course content should address topical developments that are relevant for the industry sector, preferably with concrete examples given by business life representatives. Furthermore, the new content, including examples of models and tools, should be immediately applicable in real life. Certificates upon the completion of the course are significant for participants representing industry that is regulated by sets of standards and directives.

References

- Stickdorn, M. (2018). This is service design doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World. O’Reilly Media.

- Marstio, T., Alanko-Turunen, M., Eronen, S., Huhtanen, A., Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu & Sciences, L. U. o. A. (2021). Pedagogista uudistumista oppimisen muotoilun avulla. Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu.

- Futurice. The Lean Service Creation Handbook.

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Haavisto & Nykter: Giving Access to Circular Economy for Business Leaders

- Sari Haavisto, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

- Sami Nykter, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

A Climate and Circular Economy Factory project (Haaga-Helia, JAMK, Novia) has just taken a few steps towards building a common ground for many partners to participate in building a more sustainable future. The aim is to co-create a national digital platform to support Finnish companies in their efforts to create necessary strategies to participate in circular economy.

The aim of our blog is to open our preliminary findings to interested parties and stakeholders. We will continue to share our findings during the duration of the project. We will further explore and investigate the requirements that companies have in knowledge and skills, that are needed for updating their capabilities to fulfil all EU directives and other legal restrictions, that will affect their business. We anticipate that companies are in quite different stages of circular economy, there will be companies that are forerunners, companies that are laggards. As we strive for a better tomorrow and a sustainable future, and a healthy planet for our future generations, we will share our findings as the project advances.

During the first four months of the project, we have performed some preliminary analysis, found that multiple circular economy projects, webinars, seminars, and alike have been initiated in Finland. However, a service platform, which would help companies to migrate towards circular economy does not currently exist. The data is scattered, as are the experts. Our project has taken on the task of bringing all of the aforementioned to companies with a simple click to our Circular Economy Competence Centre -digital platform.

Forces Joined to Accelerate Transition to Circular Economy

In the recent years the circular economy has gained significant attention in academic literature. It is generally viewed as one of the key concepts that can help in the struggle against climate change. Nevertheless, even the terminology among the academia is still under development (Kirchherr, Reike, & Hekkert, 2017; Prieto-Sandoval, Jaca, & Ormazabal, 2017). This reflects also to the business world. The preliminary data collected from several past and ongoing circular economy related projects have shown that companies are at quite different levels in their understanding of what circular economy encompasses. Company leaders are also at different levels of motivation and pressure to change their businesses from linear to circular economy business models. The legislative pressure is set on the EU and Finnish governmental levels.

The European Commission’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals was adopted amongst other, by Finland in 2015. The commitment to reach all seventeen of the sustainable development goals is strong. In a recent report by the Finnish Government (2020), the Bertelsmann Foundation and the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network have ranked Finland third in its implementation and development, behind Sweden and Denmark. However, much work is still to be expected. In 2020 the European Union declared its intent to become the first circular economy region in the world (European Commission, 2020). The plan includes many changes in EU legislation that will have a significant impact on how businesses operate within EU. In similar fashion, the Finnish Government has also expressed the objective of being a forerunner in many of the 2030 Agenda’s sustainability goals.

Finnish Institutions and Education at Large have Embraced the Challenge

In addition to the governmental institutions that have taken up the challenge on sustainability related issues, many educational institutions have also built up their research capabilities and capacities amongst the many areas of sustainable development. Multiple sustainability, climate change and circular economy projects and projects were initiated in the mid-2010’s, and many are still in progress today. Without a doubt, many more will also come. The actions taken suggests that many Finnish institutions commit strongly to supporting Finland’s objective of becoming the forerunner in achieving the Agenda 2030 objectives.

The curriculum on many levels of education has been updated to include various study projects around sustainability and circular economy. This also includes the universities of applied sciences operating in Finland. The universities have invited companies to join various research and development projects to co-create tools, models and networks that will facilitate and even accelerate the needed transformation from linear economy business models to circular economy ones.

Different Levels of Pressure for the Transition to Adopt Circular Economy Models

Already in 2014, large companies with more than 500 employees were struck by their liability to report social and environmental management issues determined in the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD, 2014). This forced these large companies to not only convey financial performance, but also report how their actions have impacted society and the environment. The obligation to report has also ensured that large companies have invested in capabilities and skills for incorporating sustainability into their business core. The EU has suggested extending the obligation to report also to include companies that employ over 250 employees (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive).

According to Statistics Finland, out of 368 633 companies registered in Finland, only 286 companies employ more than 500 persons. In addition, there are 354 companies who have more than 250 employees, who will now need to include environmental impact in their annual reports. This represents a very small portion of all Finnish companies. On the contrary, the size of Finnish companies is heavily skewed to small businesses. In fact, close to 95% of companies have less than ten employees. The listed small and medium sized (SME) companies of the 99,8% companies employing under 250 persons, will most likely have to adhere to the sustainable reporting requirements in the coming years.

This indicates that only a relatively small number of the Finnish companies currently have an enforced motivation set by legislation or compulsorily reporting to move quickly towards circular economy. From the preliminary findings, many large companies have indeed incorporated sustainability in several ways into their businesses’ core activities. Some can even perhaps be identified as corporate forerunners in circular economy. However, it is fairly evident that the SME companies are on a very different level in their knowledge and motivation to adopt a circular economy mindset.

Transition Roadblocks to Circular Economy

Regardless of the popularity of Circular Economy within academic literature, policy makers, and various institutions, circular economy is still unfamiliar for several companies. It might be a popular buzzword to be used in appropriate occasions, but it might not carry any meaning nor give impulse to take any actions. Hence, we identify that there are several roadblocks that lie ahead for a smooth transition to Circular Economy.

Transition from Linear to Circular Economy encompasses a wide array of necessary changes and actions in companies. For instance, the adaptation to these changes requires companies to modify the existing business models. The migration from a traditional linear towards a circular economy business model can necessitate top management participation. It can also require the leaders’ commitment to possible heavy re-structuring and changes in strategic intent. Without legislative pressure in the current business environment, when companies are still struggling with the massive impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on businesses, such migration is most likely not a top priority. Hence, survival and short-term thinking prevail over long-term initiatives in companies.

A company that would have these committed leaders still needs to invest resources in distinct phases of the transition process. The change needs to be carefully planned and managed. It might require changes in deep rooted processes and technical tools. It is likely that especially the SME companies have significant constraints with, and scarce availability of required resources to invest in the transition process.

In addition to physical resources, the companies need the knowledge and capabilities to ensure that they can take the needed actions. Again, this might be more of a challenge with the SME’s. If even the basic terminology related to circular economy is unknown, there is a fundamental lack of understanding of the fact that there is a knowledge and capability gap in the company. As adaptation to these changes requires companies to acquire new competences, which SME leaders do not realize exists, the transition is facing a major roadblock.

Even for the companies that are interested in beginning their journey in circular economy, roadblocks exist. One of these is that the information is widely scattered. There are some well-known promoters of circular economy, such as Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra. Industrial federations have also published their strategies towards climate neutrality, along with playbooks and handbooks on how companies should start the transition. Although the guide documentation can help decision makers understand the need for change, these documents need to be brought to the attention of company leaders. The scattered information needs to be made easily available. This requires more than just posting them on the institutions´ or promoters’ web pages.

This brings us to the communication related roadblock. Substantial communication efforts are needed to convince companies about the benefits of transition to circular economy. These benefits can be categorized under three important themes. The first theme, namely renewal, needs to focus on how stepping into circular economy models can bring new business opportunities. The second theme, profitability, needs to focus on how these new models can improve the profitability of the companies. The last theme, compulsory, needs to focus on legislative and alike pressures that face companies.

Legislation is still in progress, like the EU directives, and as such, very unknown to the business leaders that are struggling to cope in the fast-paced environment of today’s business world. The communication on all the aforementioned benefits should be understandable, it should resonate with the leaders in companies, and it should invite them to act. In simplistic terms, we need to harness marketing communication efforts to convince them to buy-in to a business model that is different from the current one.

Once the companies have gained understanding and have acknowledged that the competencies gap exists, and the willpower and motivation are evident, they need partners to support the transition. They will need support for the training of personnel, both current and new. This is an area where applied universities can grab the opportunity. Universities can offer all the tools, models, and insight they have gathered during the time they have built their own capabilities around circular economy.

We have, in our project, begun to co-create a service platform to help companies migrate towards circular economy. This national digital platform will support Finnish companies in their efforts to create necessary strategies to participate in the circular economy. It will offer services and training for closing the competence gap. The first step is to further explore and investigate the requirements companies have. We have commenced with the service design process plan to find the gaps of knowledge and skills that are needed for updating their capabilities for circular economy.

We will not reinvent the wheel. The aim is to identify and invite the past and current programs and projects by universities that can offer the needed data, expertise, and experts. There is a need to build ecosystems and networks that benefit all partners. The Circular Economy Competence Centre -digital platform will serve companies and also universities. With a simple click we aim to open the door for companies to find data, expertise and experts. A simple route for all partners to join us in our efforts to build a more sustainable and environmentally friendly and solid world.

The article was written as part of the Climate and Circular Economy Factory project coordinated by Haaga-Helia and co-created with Novia and JAMK. The project is financed by Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. The project objective is to create a mutual platform, Circular Economy Competence Center, for all universities to support an accelerated transition for companies and businesses to enter the circular economy network and its ecosystems.

Bibliography

- European Commission. Directive 2014/95/EU: Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD).

- European Commission. (2020). Circular Economy Action Plan. European Union.

- European Commission. (2022) Council adopts its position on the corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD).

- Finnish Government (2020). Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2030 Agenda – Sustainable Development Goals.

- Finnish Government (2020). Prime Minister’s Office. Government Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Towards a carbon-neutral welfare society. ISBN: 978-952-383-085-1.

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Structural business and financial statement statistics [e-publication]. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 4.3.2022].

- Prieto-Sandoval, V., Jaca, C., & Ormazabal, M. (2017). Towards a consensus on the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 605-615.

- Wollmert P., Hobbs A., EY. (2021) How the EU’s new sustainability directive will be a game changer.

Rahmel: Pahoista paikoista uudistuviin tarinoihin – Toivo@Tee yksin yrittäjän tukena

- Päivi Rahmel, Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu

”Minä olin juuri irtisanonut itseni vakityöstäni ja perustanut oman yrityksen, kun korona alkoi ja kaikki tyssäsi siihen. Työt loppuivat, enkä tiennyt, mitä tehdä.”

Monen yksinyrittäjän arki muuttui ennakoimattomasti ja rajusti, kun korona saapui. Useat heistä luopuivat monista asioistaan, kuten asunnostaan, autostaan, ruokatottumuksistaan, asiakkaistaan, tuloistaan ja joku unelmistaan – ja muutamat jopa työstään. Kuka meistä pystyisi tähän? Kuukauden tai kahden varoajalla.

Jonkun onnekkaan liiketoimintaan syntyi uusia mahdollisuuksia ja yllättäviä oven avauksia, jotka kiidättivät eräitä hämmästyttävään uuden luomiseen. Heistä osa pystyi tarttumaan uusiin mahdollisuuksiin, luopumaan entisisistä toiminnoistaan ja rakentamaan vauhdilla uutta. Kuka meistä pystyisi tähän? Kuukauden tai kahden varoajalla.

Uhan kohdatessa

Aikamme tunnusmerkkejä ovat ainakin jatkuva muutos ja viime aikoina täysin yllättävät jopa katastrofaaliset tapahtumat. Nämä muutokset ovat olleet selkeästi globaaleja ja jopa henkeä uhkaavia. Elämme keskellä digitalisaation kasvavaa vaikutusta, yhä jatkuvaa koronaa ja nyt viimeisenä todistamme Ukrainan sotaa ja Suomen muuttunutta turvallisuustilannetta. Miten ihmeessä näin suuriin muutoksiin tulisi reagoida? Miten voimme ennakoida digitalisaation kautta syntyvän automatisaation vaikutuksia omaan työhömme? Miten voimme kestää ja sietää pandemian tuomaa epävarmuutta? Miten voimme kohdata sodan uhkaa ja sen moninaisia ja arvaamattomia seurauksia? Miten niihin voi yksilö, yrittäjä ja yhteiskunta vastata?

Yksilöllisissä reagointitavoissammehan me olemme myös hyvin erilaisia. Olemme riippuvaisia sekä biologiastamme, taustastamme sekä ympäristöstämme. Nykyiseen trauma-ajatteluun (Odgen, Minton, Pain 2009, Van Der Kolk 2014) liittyvän teorian mukaan, meillä kullakin on oma biologiaan pohjautuva sietoikkunamme, joka säätelee toimintakykyämme vaarallisiksi koetuissa tilanteissa. Jos jokin uhka ylittää tämän henkilökohtaisen sietoikkunamme rajat, me kerta kaikkiaan lamaannumme tai joudumme ylivireystilaan, jossa toimimme usein tilanteen kannalta epätarkoituksenmukaisesti. Näihin tilanteisiin on tarpeellista löytää toimintaa, joka rauhoittaa ja auttaa meitä palautumaan omaan sietoikkunaamme ja sitä kautta takaisin toimintakykymme pariin.

Rauhoittavaa toimintaa on monesti hyvin konkreettisiin asioihin keskittyminen ja siitä varmistuminen, mikä selviytymiseen vaikuttava tekeminen on omien mahdollisuuksien rajoissa. On tärkeää tunnistaa, mitä asioita tekemällä ei itse lisää muutoksen tai uhan tuomaa kuormaa itselleen, läheiselleen yhteisölleen tai yritykselleen. Miten erottaa oma, toisten ja yhteiskunnan toimien vastuu kussakin tilanteessa. Vertaisiin liittyminen ja vertaiskokemusten jakaminen on myös merkittävä apu omien kokemusten suhteellistamiseen ja mahdollisuus siihen, ettei jää yksin vaikeiden asioiden pyöritykseen. Yhteisöön liittyminen ja yhteisöön kuuluminen tuo turvaa epävarmuutta luovien tapahtumien pyörteissä.

Voimauttavat tarinat, uudet näkökulmat

Metropolian ja Laurean yhteisessä ESR-rahoitteisessa Toivo@Tee-hankkeessa (14.2021–31.3.2023) on tuettu yrittäjiä korona-ajan haasteissa. Hankkeessa on useita erilaisia toiminnallisia osioita eli Campeja, ja tässä tekstissä paneudutaan työskentelyyn kriisin ytimessä, In Crisis nimisessä kokonaisuudessa. Työskentely on perustunut narratiivisen lähestymistapaan (Bruner 1986, Fox 1994, Drake 2017, Kinossalo 2021, Rahmel 2019, 2021, Torkki, 2014, White 2008) ja sen soveltamiseen oman yritystarinan ja oman yrittäjäidentiteetin kirkastamisessa ja uudistamisessa. Työskentelyssä on tutustuttu, tunnistettu ja tiedostettu oman tarinan rakentumista yrityselämän eri vaiheissa ja kokonaisuutta on syvennetty voimauttavan valokuvan (Savolainen 2018) ja narratiivisen valmennuksen työskentelyprosessissa.