Introduction

This publication is part 1 of our strategic analysis and insight of the Finnish tourism, hospitality and experience (including hotel, restaurant, and experience companies) cluster (THE cluster) before COVID-19, during the pandemic and a business foresight in the period when COVID-19 risks have reduced.

This first study will focus on the strategy- and future orientation of the Finnish THE cluster before COVID-19 crisis. Our research interest is to analyse how the THE cluster organisations (including companies and public travel organisations) were focused on their strategic business and foresight analyses before the special business conditions of COVID-19 crisis emerged in Finland.

The state of international emergency caused by the COVID-19 crisis has raised many kinds of discussions and reflections on the future of tourism and hospitality industries, especially travel agencies, aviation companies, safari companies, restaurants, hotels, and event companies, throughout the world. For the THE industry the COVID-19 crisis has been an economic, social and cultural shock in many ways. We have seen new calculations, models, and predictions of global and country-level virus progression every day. The risk society discussion has returned and changed to the new normal. Risk society discussions are now very lively and vital (e.g. Beck 1992, Nygren & Olofsson 2020).

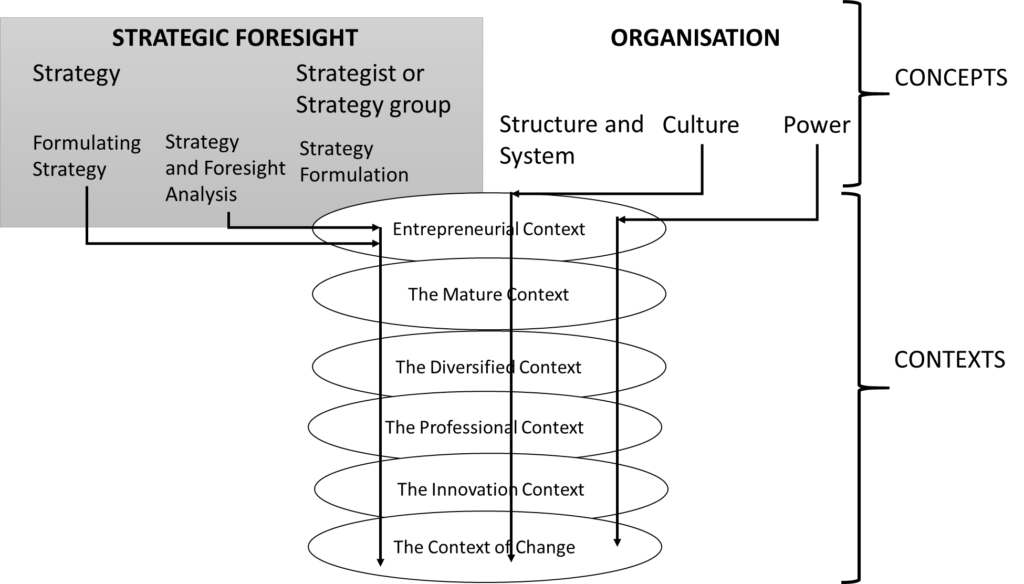

Our THE cluster study with case studies is focused on strategic foresight paying attention to (1) formulating strategy, (2) strategy and foresight analysis in the business of THE cluster and (3) strategy formulations of the THE cluster companies and public travel “visit organisations”. We leave out of this study right-hand elements of organisations, structure and system, culture, and power aspects. These socio-cultural issues are highly relevant, but because of the textual space limitations of an article, we are forced to focus on key foresight issues.

We have defined three major research questions:

- How have the Finnish THE industry and tourism strategy authorities and experts been prepared for the future in their strategies?

- What kind of strategic landscape do they have before COVID-19?

- What kind of risk analysis have they done as an elementary part of their business strategies?

These three questions are general research questions, that we want to answer in this study.

Objectives and goals

The key research questions are, how the chosen Finnish companies and organisations were analysing and predicting their business and decision environment and how they saw the future trends. On the meta-level, this paper depicts the strategic foresight thinking of the Finnish THE industry. This paper concentrates on organisational strategy and risk analysis of tourism and hospitality case studies.

In this study, we focus on the perspectives of seven Finnish THE organisations and agencies. We are investigating the key strategic documents of the biggest most effective and important and precisely chosen Finnish tourism, hospitality, and experience organisations and associated policy agencies: (1) the Visit Finland (2) the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment (3) Finnair, (4) the Finavia, (5) the Scandic Hotels, (6) the NoHo Partners and (7) the Regional Council of Lapland.

We are also reporting some experiences and learnings from Finnish tourism, hospitality and experience industry from years 2008-2019. In this study, we underline obvious and vital needs to re-evaluate the practices of the foresight and management systems of THE cluster in Finland.

Our meta-objective is to get a better understanding of what we can learn from the era of business growth and time before the socio-cultural and economic crisis and during COVID-19 period in Finland. This is one key motivational scientific aspect of this empirical case study.

As we know, theoretically approaching the research problem, foresight and strategic thinking can be linked to the need to limit the intellectual knowledge space of bounded rationality and opportunism. Because of unobserved risk and uncertainty, there will always be some space of bounded rationality, but with professional strategic planning and foresight research, we can always limit the knowledge space of bounded rationality (see Williamson 1998). If the intellectual knowledge space of bounded rationality is very broad and not limited in any ways, we can logically expect more unintended consequences than in the case of smaller intellectual knowledge space of bounded rationality. If this intellectual knowledge space of bounded rationality is non-existing, we can expect full rational behaviour without any unintended consequences. This kind of full rationality assumption (“perfect knowledge”) is often made in the field of economic theory. This is a relevant aspect of strategic thinking. This is also the main motivational aspect to perform our case studies.

Research data

Our research material covers key strategic documents of the THE cluster´s main operators, power players and policymakers. We have analysed the open strategy documents and business statistics and characteristics of seven key organisations. We have made content, diagnostical analysis, and strategy analysis of different tourism and business strategies, tourism policy reports, consulting and business reports, destination and tourism development reports, digitally available marketing reports, annual and interim reports.

Our second research methodology is a case study research methodology. Our case studies cover

- Case study package A with (1) diagnosis analyses with (1.1.) strategy analysis, (1.2) target markets analysis, (2) prognosis analyses (what tourism, hospitality and experience business will be in the future and (3) prescriptions (strategic recommendations for the tourism, hospitality and experience business).

- Case study package B covers (1) Time horizon of trend and scenario analyses (Short run: less than one year, middle-range: middle run: 2-5 years and long-run: more than 5 years.

- Case study package C covers Qualitative or Quantitative Trend analysis.

- Case study package D includes analysis of special elements of foresight analyses.

- Case Study package E includes analysis of Passive, Reactive, Active and Proactive classification.

- Case Study package F covers Risk perspective analysis with classification Risk-averse organisation, Risk neutral organisation and Risk lover organisation.

- Case Study package G includes very basic business model analysis with a classification Growth-oriented model, Sustainability oriented model and No any business model.

These seven case study packages provide comprehensive information about the case study organisations and their strategy elements, formulations, strategic foresight analysis and strategy formulations. This way, we want to create a big picture of the Finnish THE cluster. Our methodological approach includes European ForLearn (2020) recommendation of foresight research, which includes (1) Diagnosis phase, (2) Prognosis phase, and (3) Prescription phase (DPP-methodology package). Our aim with seven analyses is to provide comprehensive information about the strategy and strategic architecture of the Finnish THE cluster and its key agencies of the tourism industry.

Limitations

We know that the core of Finnish THE business context includes always the national and international business environment outside the organisations, and their networks. We are aware of diversified and complex contexts of business. We also know those decision-makers in THE business have their own values, missions, visions, and business experiences and knowledge, competencies and the organisational models of management and leadership (see e.g. Mintzberg & Quinn 1998, 24-25).

Thus, we want to clarify the methodological limitations of our analyses in this tourism, hospitality, and experience industry case study analysis. We focus on Finnish country cases and observed experiences. We limit our investigation to highly relevant and available, open, strategic documents of those key tourism, hospitality, and experience cluster players in Finland. We trust on their official business announcements and documents for stakeholders because it is impossible to get precise strategic statistics of revenues and costs of case companies and their business units.

We are not analysing their business actions and strategies during COVID-19 crisis because there is a need to analyse these operations and strategic choices on other issue and in second and third parts of this research. Our study has a clear focus on the early phase of COVID-19 crisis. Such contextual organizational issues are global structures and systems, cultural aspects, and power relations (see Mintzberg & Quinn 1998, xi). Such socio-cultural aspects are among others, distance to power and uncertainty avoidance. In this Finnish THE cluster and country study, we limit our analysis to strategy issues like strategy formulations, strategy and foresight analysis, and final formulations of strategy.

The framework of the study

The framework of the study is linked classical strategy process theme diagram (Mintzberg & Quinn 1998, xi), which we have modified a little bit to link foresight activity to our case study framework (Fig. 1). Our focus of the THE case study program (seven cases) is marked with grey colour in the left side of Figure 1.

The top image shows key theoretical concepts, which are mentioned in the mainstream theoretical theory. At the bottom of the image, the theoretical concepts are presented. The strategy of business administration includes strategy formulations and strategic and foresight analyses. The concept of the organization includes organisational structure, system culture, and power structures. An organisational strategy is normally implemented in various contexts. The contexts can be defined in the following ways. We describe these contexts in the following ways.

Entrepreneurial context is often very simple, focused, and dynamic. Typically, it must be very small, flexible, and allow rapid decision-making. (Mintzberg and Quinn 1998, Chapter 9.)

The Mature Context is the operational core and administration of a business administration. Call it the machine organisation, which takes care of all operations. This part of the organisation ensures that the business tasks are carried out. (Mintzberg and Quinn 1998, Chapter 10.)

The Diversified Context is typically linked to business recombination strategies and combined integration and diversification strategies. This context will be needed, when a firm extends its core business and makes cost-of-entry tests and tries to control the diversification process. (Mintzberg and Quinn 1998, Chapter 13.)

The Professional Context is based on coordination on the standardisation of skills, which is achieved primarily through formal training. There are various sub-groups of specialists. The Professional Context hires duly trained specialists and professionals. This section of business administration has a more independent role but their relationship to consumers and other professionals can be very close. (Mintzberg and Quinn 1998, Chapter 11).

The Innovation Context is typically linked to the idea-invention-innovation process, which requires special innovation management skills. Some scholars call it “controlled chaos” (Quinn 1985). The Innovation Context requires the operating adhocracy and administrative adhocracy. (Mintzberg and Quinn 1998, Chapter 12). Typically, all other contexts of business administration are more or less focused on “inside-the-box” thinking, but the Innovation Context must be focused on “out-of-box” thinking. Of course, organisations, who do not make any strategies or risk analyses, expect that they can live and survive with any unintended consequences. This can, however, be a wrong strategic assumption, if an organisation cannot survive with its strategic choice and operational decisions. There are always alternative institutional arrangements, which would yield new benefits from the reductions of agency costs (see e.g. Demsetz 1967, Jensen & Mecking 1976). We know that some organizations are taking more risks (risk-loving organisations), while some organizations are risk-averse (risk-averse organisations). Some organizations are “middle-of-the-road” risk-takers.

Our basic theoretical assumption is that organisations typically have listed organizational contexts, which actually lead to organizational business foresight and strategic decision-making.

Strategic foresight and risk thinking

The foresight and risk-taking approaches are elementary aspects of strategic thinking. As Herbert Simon noted, weak-form selectionism entails “survival of fitter”, but not the “survival of the fittest” principle (Simon 1983). This kind of theoretical discussion is, of course, interesting, but in this study, we prefer to adopt Herbert Simon´s evolutionary approach, which underlines the principle of “survival of fitter”. From this perspective, we can note that it is wise to manage risks and uncertainties by aiming to be strategically fitter than other competitive organisations, which may take too big risks in their business strategies and not be to fit enough.

In Figure 2, we have visualised the impact of strategic foresight on the space of bounded rationality. The simple idea is that the space of bounded rationality will be smaller in the case when strategic foresight activity is implemented than in the case it is not implemented. Only in the case of perfect foresight, we could eliminate the space of bounded rationality, but in reality, this will not happen with easiness, when we talk about human beings and their real-life organisations.

Figure 2. Bounded rationality with professional strategic foresight and without it.

The top image shows key theoretical concepts, which are mentioned in the mainstream theoretical theory. At the bottom of the image, the theoretical concepts are presented. The strategy of business administration includes strategy formulations and strategic and foresight analyses. The concept of organization includes organisational structure, system culture and power structures. Organisational strategy is normally implemented in various contexts.

The Strategy of Finnish Tourism, Hospitality and Experience cluster

Today tourism provides livelihoods for millions of people and allows billions more to appreciate their own and different cultures, as well as the natural world. For some countries, it can represent over 20 percent of their GDP. Overall, tourism is the third-largest export sector of the global economy. Tourism is one of the sectors most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting economies, livelihoods, public services, and business opportunities on all continents. In 2020, scenarios for the sector indicate that international tourist numbers could decline by 58 per cent to 78 percent in 2020, which would translate into a drop in visitor spending from $1.5 trillion in 2019 to between $310 and $570 billion in 2020. This placed over 100 million direct tourism jobs at risk. Many of them in micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) which employ a high share of women and young people. Informal workers of the tourism cluster are the most vulnerable. (United Nations 2020, 2.)

From this global perspective, it is very important to study the COVID-19 crisis also at the Finnish national level.

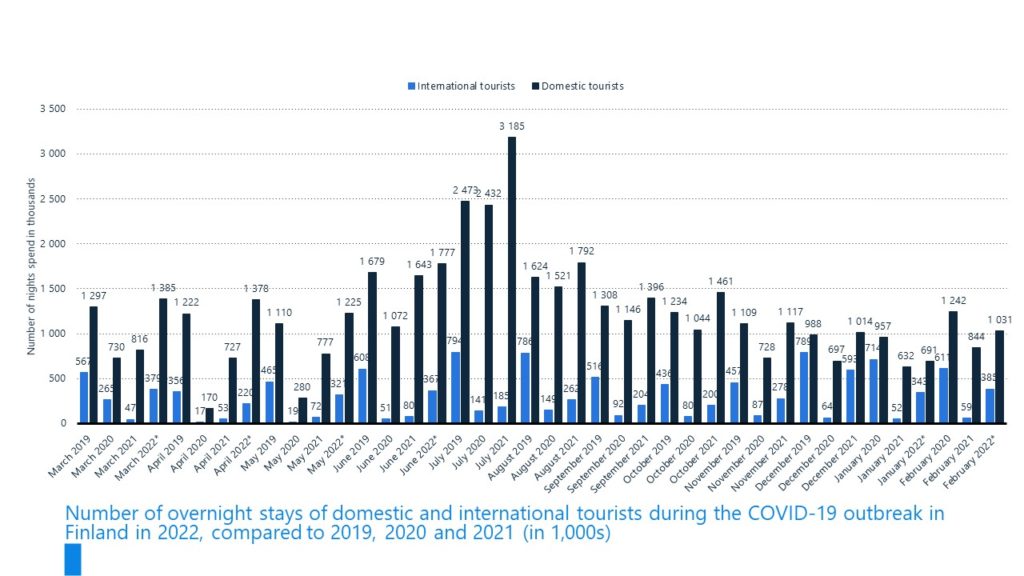

In Figure 3 we report the number of overnight stays of domestic and international tourists in Finland during the COVID-19 outbreak in Finland in 2022, compared to 2019, 2020 and 2021 (in 1,000s).

Figure 3 visualises tourism development changes after COVID-19 crisis. Figure 3 shows comparisons of years 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. We see that impacts of COVID-19 have been strong and negative for domestic and international tourism.

On the meta-strategic level, Finland has tried to construct its tourism, hospitality, and experience industry´s competitiveness ideology and the causal topology of economic emergence by marketing its competition edges and key words: credible, coolness, creativeness and contrasting (C4 edges). In the national and regional tourism strategies, the tourism authorities and companies have defined the strengths and future main products and development areas. In many business strategies and plans during the modern Finnish tourism economy, trust has been put the growth of foreign tourism and consumption of experience and well-being services. (Elinkeino- ja innovaatio-osasto 2015; 2014; Finnish Tourist Board 2008a; 2008b; 2005; Hänninen 2020; Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 2019; Suomen Matkailustrategia 2015).

The Finnish strategies and tourism objectives during the period 2009-2020 and 2021-2030 are aiming for sustainable growth. The key goals of those national tourism strategies are conceptual, operational and international business oriented:

- Development of experience and wellness concepts

- Serialisation and productisation of THE companies

- Internationalization, networking and joint marketing of THE companies

- Identification, developing, marketing and selling of core well-being products and services

- Development of service and technology innovations of well-being tourism

- Development of year-round service offering and sales

- Improved quality

- Cooperation in distribution and pricing with international distribution channels

- Sustainable service development

These key goals have also defined various tourism sector research projects and R&D -service research projects (Björk 2011a; Björk 2011b; Björk & al. 2011; Finnish Tourist Board 2008a; 2008b; 2005; Hänninen 2020; Konu 2010; Konu & al. 2011; Konu & al. 2010; Konu & Laukkanen 2010; Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 2017; Suomen Matkailijayhdistys SMY ry ja Suomen Matkailun Seniorit 2009; Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö 2019; 2015; 2014; 2010; Visit Finland 2019).

In this sense, Finnish tourism and hospitality industry and associated service innovation cluster share this kind of multiple and sustainable Finnish business vision and mission from 1970 until 2030 (see Hemming 2012; Häyhä 2011; Matkailun edistämiskeskus 1978; 1982; Suomen Matkailijayhdistys SMY ry ja Suomen Matkailun Seniorit 2009; Suomen matkailun tulevaisuuden näkymät Katse vuoteen 2030 2014; Valtakunnallinen matkailustrategiatyöryhmä 2006) before the global tourism collapsed dramatically because of COVID-19 crisis.

During the last twenty years, The Finnish THE industry, destination marketing organizations (DMOs) and the Visit Finland tourism development organisation have constructed their strategies on growing tourism markets in the Northern Europe and increasing International demand of Finnish experience and hospitality services and products (see Hemming 2012; Lehtonen 2009; Matkailun edistämiskeskus 1991; Nurmi & al. 2019; Suomen matkailun tulevaisuuden näkymät Katse vuoteen 2030 2014; Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö 2019a; 2019b; 2015; 2014; Valtakunnallinen matkailustrategiatyöryhmä 2006). The positive belief and understanding of business growth have also been based on the World Tourism Organizations (2020: 2017) tourism statistics and predictions and European Union tourism policy (see Eurostat 2020; Weston & al. 2019).

The strategy and foresight thinking of the Finnish THE cluster is also very EU-based and state-based. The World Tourism Organization has predicted that EU and especially Northern-Europe has succeeded in their normative and operational actions regarding sustainability, competitiveness, multilevel-governance, and impact, and the branding of europeanisation to increase the tourism volumes (Estol, Camillieri & Font 2018; Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö 2019a; 2019b; 2015; 2010; Weston et al. 2019).

During the same period, the aviation companies have to expand their routes from Asia and America to Europe (EU Transport in Figures 2019). Only, at Helsinki-Vantaa Airport has the passenger volume from 2010 to 2019 grown from 10 million to 22 million passengers (Finavia Nd). The main increase of flight travellers came from Asian transport.

The strategy and foresight thinking of Finnish tourism and hospitality are also very regional-based. The most developing and growing areas have been Helsinki, Lapland, Oulu, Tampere, Turku and Lake Finland. Finnish main cities have invested in new service infrastructure: airports, arenas, harbours, hotels, meeting and exhibition centres, culture houses, music halls, and transportation services. The THE cluster is approved as a vital part of brand management, and revenue and employment strategies. For Lapland, Helsinki, Turku and East-Finland the THE industry cluster is recognized as an important business area. The regions started to update the tourist and service strategies and foresee huge potential on tourism business growth and are launching huge master plans and investment projects. (Heikkinen 2020; 2015; Häyhä 2011; Matkailun Edistämiskeskus 1975; 1978; 1982; 1991; Pihlström 2011; Pihlström & Tarasti 1996; Sievers 2019.)

The dot-com bubble of 1995-2000, the short business depression in 2018, the eruption of Eyhafjafjallajökull in Island in 2011 and the coronavirus pandemic, have indicated the vulnerability of the global companies in the THE industry. The tourism season year 2019 was the best in Finland and in March 2020 foreign tourism stopped totally. Many firms had to shut down the doors in the middle of the main winter season. During the beginning of the second wave of the corona, the Helsinki and Lappish hotels, resorts and restaurants were thinking to close again. The flights were cancelled and ferries stayed at harbours. The state had to ease and increase travel restrictions. (Market Line 2020, 27th April, 78; Rafat 2020.)

In Figure 4 we have presented the effects of COVID-19 on the Finnish THE industry cluster. This analysis shows the bad state of the cluster in spring 2020.

Figure 4: The effects of COVID-19 to the Finnish THE-industry cluster in long-, mid-term and short-term (Heikkinen 2020; Market Line 2020, p. 78).

After presenting relevant background analyses we move now to seven special case studies of the THE cluster.

Case Study 1: Visit Finland

Visit Finland is a Finnish expert travel agency responsible for promoting Finland as a tourist destination on the international markets. Its main task is to promote the Finnish THE cluster through marketing communications. The organisation is a unit of Business Finland and receives its funding from the state budget. Visit Finland and the tourism, hospitality and experience industry conduct joint product campaigns and arrange fact and emotion finding visits for foreign travel operators and the media to support the promotion of Finland as an experience and attractive destination.

Visit Finland helps to facilitate investments to the Finnish THE cluster as well as promotes Finland as an international business, culture, sciences, education, and sports events destination.

It also acquires market and customer insight and foresight information for the industry and promotes product, service, and experience development. The organisation is also increasing awareness of the competitive operating environment and supporting companies, and destinations growth and renewal. In Table 1 the analysis of case analyses of Visit Finland is reported.

| Case Study 1: Visit Finland | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| Visit Finland develops and markets Finland’s travel image and brand as well as helps Finnish travel companies to internationalise, develop, sell and market travel products and services. Visit Finland helps to facilitate investments to the Finnish THE cluster as well as promotes Finland as an international business, culture, science, education and sports event destination. Visit Finland´s strategy is the combination of strategic travel roadmap done by Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and strategy of export done by Business Finland. Strategic priority areas of the roadmap: *Strengthening theme-based co-operation between tourist centres and networks of tourism companies *Strengthening product development and international sales and marketing *Developing competitive and comprehensive offerings of tourism and experience services *Increasing the effectiveness of marketing activities and making the travel services easier to buy *Increasing understanding of competitive operational environment *Supporting companies and destinations growth and renewal | Analysis A: Theme-based co-operation The strategy focuses, as earlier tourism strategies, on co-operation between regional organisations and destination marketing organisations (DMOs) and companies. It believes in Finnish thematic (experience, nature and culture tourism) strengths and in developing year-round tourism. The strategy believes that Finland can offer original and intriguing tourism services and products to inbound and domestic tourists. Analysis B: Product innovations and competitive and comprehensive offerings, sales and marketing The strategy aims at international target markets by developing products, organising joint promotions and campaigns and effective digital marketing. It wants to strengthen the digital competencies of tourism companies and DMOs. The strategy aims to develop the national parks.fi and excursionmap.fi digital communication services in terms of content and produce materials for use in the tourism industry’s marketing and communications Analysis C: Easy accessibility The strategy part of transport development is strategic and practical. It claims resources to invest on rails, roads and airports. | Passive: The strategy aims to improve the condition of the rails and road network, but Visit Finland has only an advisory role. Reactive: Visit Finland encourages DMO´s and companies to co-operation. It develops Finnish tourism competitivity and competition edges, but resources are very low compared to other Scandinavian countries. Active: Finnish tourism strategy is a combination of mega trend analysis, strategic road maps and scenarios. It finds growing competition, but at the same time, it can´t give any financial resources for competition. Proactive: The strategy supports internationalisation and image promotion. It also presents directions on strategic decision making of regional tourism strategies, municipalities, politicians and authorities, who are not responsible for the business. Risk-averse: The strategy part of eco-efficient service production development is declarative and realistic. It supports alternative energy production and transport options but admits how difficult it is to reduce the carbon footprint. Risk neutral: PESTEL-analysis is a basic description of existing phenomena. The strategy is very operational and tactical, where market representatives arrange sales activities, follow the markets and their development and gather market data for further analysis. Risk lover: The strategy recognizes the importance of climate change, but it does not give any tools for the industry to develop its facilities’ eco-efficiency. |

Case study A indicates the realism and relevancy of priorities of the Finnish tourism strategy. The strategies and roadmaps of Finnish tourism has been based on natural strengths. The competitivity is grounded on basic leisure and experience products and co-operation between tourist centers and networks of tourism companies.

Case study B shows the importance of product, service and experience development. Visit Finland does not have resources to increase the traditional marketing activities but invest on digital and virtual marketing.

Case study analysis C emphasises the digitalisation of Finnish tourism organisations, which increases effectiveness of marketing and selling.

Case study D shows how important it is to reinforce Visit Finland’s greater region cooperation between the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, Lapland, the lake region and the coast and the archipelago region.

Case study analysis E indicates the importance of developing year-round supply by developing tourism products and service structures within the themes of nature tourism, health tourism, food tourism, culture tourism, and sustainable tourism.

Case study analysis F shows the dynamics and complexity of future tourism strategies, road maps and action plans although they have been prepared by several ministries, their administrative branches and the working group on tourism composed of business representatives.

Case study 2: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment

The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment (the MEAE), as part of the Finnish Government, creates the conditions for economically, socially, and ecologically sustainable growth, which is thought to happen through skilled people in high-quality jobs, productivity, and increasing employment.

The ministry is responsible for industrial and tourism policy, innovation and technology policy, internationalisation of enterprises, the functionality of markets, promotion of competition and consumer policy, employment, and unemployment matters, as well as public employment services and work-environment issues. It is also responsible for regional development and co-operation areas of the regional councils, implementation of the climate policy at the national level.

The MEAE is responsible for setting the strategy and priorities of the Finnish tourism policy. It develops the tourism business sector in co-operation with other ministries and sectoral actors. It is also responsible for the coordination of the measures supporting tourism, drafting of tourism legislation and for tourism relations between nations.

The ministry takes part in the decision-making of international tourism matters in the European Union and other international co-operation bodies, like the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, the Arctic Council and the Nordic co-operation. Development of tourism is also closely connected with regional policy, which is also the responsibility of the MEAE.

In Table 2, we have analysed the Finnish tourism strategy and scenario work (2019-2028) which is based on four key priorities. The MEAE strategy (a) enables sustainable growth and renewal of the tourism sector: (b) supports activities that foster sustainable development, (c) responds to digital change, (d) improves accessibility to cater to the tourism sector’s needs, and ensures an operating environment that supports competitiveness.

| Case Study 2: The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment is in charge of the national tourism scenario and strategy work in Finland. The tourism strategy has based on the roadmap for growth and renewal in Finnish tourism 2015– 2025. The strategy was updated in 2019. The horizontal expert group on tourism played a key role in the update. The name of Finland’s national tourism strategy for 2019–2028 is “Achieving more together – sustainable growth and renewal in Finnish tourism”. The strategy defines targets for the development of tourism until 2028 and measures to be taken between 2019 and 2023. Finland is aiming to become the most sustainably growing tourist destination in the Nordic countries. Tourism is seen as a growing service business that generates welfare and creates jobs across the country. The Tourism Strategy and scenario work (2019-2028) is based on four key priorities: *Enabling sustainable growth and renewal of the tourism sector *Supporting activities that foster sustainable development *Responding to digital change *Improving accessibility to cater to the tourism sector’s needs, and ensuring an operating environment that supports the competitiveness of Finland, regions and destinations. (Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö 2019.) | Analysis A: Sustainable growth Finnish Tourism Strategy considers sustainable growth and renewal of the tourism sector as an important role in ensuring Finland’s future competitiveness. The strategy describes current and future economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts for stakeholders from a pre-corona time perspective (before March 2020). The strategy supports industry to increase the profitability and qualitative growth of the sector. It crystallizes well Nordic countries’ values, functional infrastructure, lawful operations, regular tax and salary paying, cultural heritage, SME enterprise’s roles and impacts of employment, remaining cash flow in the destination, Analysis B. Digitalization The strategy emphasizes digitalising of tourism products and services and tourism marketing. It supports to promote the updating of information, equality of services among different target groups and improved cost-effectiveness. It gives the responsibility of digitalization processes and operations for enterprises and regional organisations, especially DMO´s. Analysis C: Improving accessibility The history and future of Nordic tourism is based on good transport connections and logistics. State-based ownership and its financial support for transport companies and airports are essential for regional tourism, especially for Lapland. Analysis D: Climate change The strategy supports reduction of the carbon footprint. It requires political decisions and international agreements to reinforce the sector’s own decisions and to support changes in the consumption behaviour of tourists. | Passive: The strategy doesn´t include any global and regional economic risk analysis. The strategy recognizes the importance of climate change, but it does not give any tools for the industry to develop its eco-efficiency. On an operational level, the transport strategy depicts electrified rail network plans from Russia, as well as the development of passenger transport services from airports to destinations. It doesn´t foresee any fast railway connections from Moscow and Asia. Reactive: The strategy describes well, how experience producers are competing globally, and that the industry is hyper-connected with international platforms being also vital partners. Active: The Finnish tourism strategy is a combination of megatrend analysis, strategic road maps and scenarios. It recognises the growing competition offering basic solutions for competing. Proactive: It supports decision making and co-operation between industry, politicians and authorities. Strategy expresses possibilities, but it does not promise any resources for developing and implementing them. Risk averse: The strategy is controversial. It speaks about sustainable growth and presents a lot of operations, how to compete in hard markets, but the competitor analysis is poor. Risk neutral: The PESTEL analysis of strategy is a basic description of existing tourism phenomena without sufficient risk analysis. Risk lover: The strategy claims new business models and supports growth-oriented service and quality development. |

Case study analysis A indicates that the strategy of the Finnish Tourism Strategy considers sustainable growth and renewal of the tourism sector as an important role in ensuring Finland’s future competitiveness and competition edges.

Case study B indicates clearly, how important the state´s role has been and will be. In the post-COVID-19 virus business situation, the companies need more and new financial support for business costs to prevent a wave of bankruptcies and job losses. The Government in Finland has promised to help companies get back on their feet after the COVID-19 crisis and avoid layoffs turning into redundancies.

Case study analysis C is crucial. Finland’s tourism competitiveness is based on good transport connections and logistics. The access factor is strongly underlined because Finland has a peripheral location.

Case study analysis D is also vitally important. It indicates that the Government is aiming to reduce the carbon footprint.

Case study analysis E shows that the tourism strategy is missing global and regional economic risk analysis. This issue is neglected in the national strategy.

Case study F indicates the importance of the transport strategy but it does not acknowledge and predict the electrified rail network plans from Russian and China to Europe. It does not foresee any fast railway connections (bullet trains) from Moscow and Asia.

Case study G shows how Finnish tourism strategy´s glocal development trends and dynamics, but the same time how inflexible it is, but stable. It is a combination of conventional megatrend analysis, strategic road map and business-as-usual scenarios. It recognises the growing competition offering basic solutions for competing without sufficient risk analyses.

Case Study 3: Finavia group

Finavia Group (Finavia) provides air traffic services for airlines and passengers. It has two business areas: Helsinki-Vantaa Airport and the Airport Network. Finavia’s air traffic services are supplemented by Finavia’s subsidiary Airpro Oy, and its subsidiary RTG Ground Handling Oy. Also, Finavia is a shareholder (49 %) of LAK Real Estate Oy that owns, manages, and lets office and logistics premises in the Helsinki Airport area. (Finavia 2020b.)

Finavia is a state-owned airport operator aiming to make smooth travelling. It develops and maintains passenger terminals, the infrastructure required by air traffic and service infrastructure at terminals. The network of airports consists of 21 airports across Finland. In Finland 19 airports serve primarily passenger transport. (Finavia 2020a.)

Helsinki-Vantaa Airport is the main airport of Finland and a leading European long-distance and transit hub to Asia. Finnavia´s vision is to offer the best connections between Northern Europe and the rest of the world and to promote Finland as an attractive and easy-to-reach destination on the European continent.

In 2019 Finavia was serving more than 80,000 passengers, and thousands of other customers and partners every day in Finland and abroad. Finavia´s revenue in 2019 was EUR 389 million, and it employed 2,775 people. Revenue is comprised of air traffic income, the rental income from business premises and property, as well as parking income. Finavia’s operations are not subsidised by tax revenue. (Finavia 2020a; 2020b.)

The business strategy of Finavia is linked to flight transport connections between Asia and Europe, which is expected to grow strongly. At the same time, the competition between international airports is expected to increase. To remain a player in the international competition, Finavia aims continuously to improve the operations and services of airports. (Finavia 2020a; 2020b). In Table 3 the analysis of the case of the Finavia is reported.

| Case study 3: Finavia | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| Finavia is an airport operator aiming and enabling to make smooth travelling. It develops and maintains passenger terminals and the air traffic infrastructure. It also takes care of passenger travel safe. Finavia manages the Finnish national airport network. It´s network of airports consists of 21 airports across Finland. Finavia also controls Finnish airspace and provides traffic control services, which is rare in international comparison Finavia´s vision is to offer the best connections between Northern Europe and the rest of the world, and to promote Finland as an attractive and easy-to-reach destination Helsinki Airport is a main airport and a leading European long-distance and transit hub. It competes over Asian flight connections with Stockholm, Berlin and Copenhagen. The airports in Lapland are vital for serving its travel and tourism industry. | Analysis A: Growth In short and long term, the growth of air travel is expected to continue all over the world. The growth in Finland is coming from Asia. Also, The Finavia wants to offer the best flight connections in Northern Europe, a customer experience of exceptionally high quality, as well as responsible growth and profitability. The development programmes of the Helsinki Airport and Lapland airports are preparing for future growth. B: Ecologic responsibility Finavia has paid more attention to developing responsibility and cost-effectiveness. As a result of climate goals, its entire airport network is now carbon neutral. The electrical power consumed by its airports is now completely produced with renewable wind and solar energy. Field vehicles are powered with diesel fuel made of waste materials and leftovers. Analysis C. Improving the customer experience Finavia’s mission is to offer a unique customer experience and the best passenger experience in Europe in its size on category. Finavia makes continuing investments in Helsinki Airport. It is aiming to develop the customer experience of Asian travellers to gain a better understanding of their culture and needs regarding language and services. Analysis D: Route development Finavia is offering the best flight connections in the Nordic area and profitable and responsible growth. Also, the good business connections and position of Helsinki-Vantaa Airport in Asian traffic was enhanced by Finnair’s new routes and additional scheduled flights, as well as routes to Helsinki, opened by three Chinese airlines. | Passive: Finavia´s main risk strategies are linked to the EU regulation on aviation and instructions on security control. Business risk has been linked mainly to aviation companies business situations and sudden natural disasters. Reactive: In spite of the intense competition, Helsinki Airport has succeeded in increasing its share of the transit traffic between Asia and Europe. The new routes will also open opportunities for Finnish airlines to obtain new flight rights to China. Active: The new route development takes a lot of time and resources. New connections were successfully opened after long discussions with Chinese airlines. The purpose of Helsinki and Lapland´s Airports development programmes is future growth. In strategy work, Finavia also focused on good management, the personnel’s capacity to work and the development of personnel and partners satisfaction. Risk more averse and risk-neutral: Finavia is constantly collecting feedback from people working at the airports. As the development programs progress, the company claims to make quick changes and improvements, for example, regarding access routes. Risk lover: New route openings to China tell about active risk-taking and strategic thinking. |

The summary of a Case study A. The growth of air travel in Finland is due to the increasing Asian travel. Helsinki-Vantaa Airport has been and will be an important gateway for Asian passengers. The number of passengers using Finavia’s airports increased by 4.2 %. In Europe, the volume of freight traffic decreased by 1.9 %. At Finavia’s airports, the amount of cargo transported by airlines increased over 13 %. In the longer term, the growth of air travel is expected to continue. The market outlook is promising, particularly in Asia.

Case study B shows over 4 % increase from the year 2018. A total of 26 million passengers flew on scheduled and charter flights. The number of passengers travelling through Helsinki-Vantaa Airport was 21.9 million, an increase of 4.9 % from 2018. The market position of Helsinki-Vantaa Airport strengthened in comparison to other Nordic hub airports. The number of transfer passengers on international flights increased by almost 17 %. This was the first time that Helsinki-Vantaa Airport served more transit passengers than Copenhagen Airport.

Case study C indicates internationalisation. At the end of the year, Helsinki-Vantaa Airport had direct flights to 186 (162 the year 2018) international destinations. During the year, three Chinese airlines commenced flights to Helsinki-Vantaa airport. These openings showed that Finland is seen as an attractive destination in China and Japan.

Case study D shows the growth of regional airports. The passenger volume of regional network airports increased by 0.6 % to a total of 4.2 million. Of the biggest airports, the growth was highest in Turku (+22.6 %) and Rovaniemi (+2.6 %). A total of 1.5 million passengers went through Lapland airports in 2019, an increase of 1.5 % from the previous year. Finavia’s airports handled a total of 125,869 commercial flights (scheduled, charter, taxi and cargo flights) in 2019 (+0.2 %).

Case study E shows that the rapid growth of air travel ended already in 2019 due to the weakened outlook of the global economy and trade disputes. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the passenger volumes decreased by the end of March by 95 % from the year 2018. In January–March 2020, the passenger volumes decreased by 20 %. The total number of passengers was 4.9 (6.1) million. The total number of passengers was 4.9 (6.1) million, showing a decrease of 20 % from January–March 2019. The revenues totaled EUR 86.7 (102.3) million decreasing 15 % and operating margin before extraordinary items was EUR 21.1 (31.2) margin decreasing over 32 %.

Case study F shows that climate change was an important topic also for Finavia. Its ecologic mission is to achieve carbon neutrality. Finavia was involved in the development of travel chains combining flying as a smooth and environmentally efficient part of other modes of transport. Finavia continued its determined efforts to reduce its emissions. Net-zero emissions are their future goal. It means that Finavia’s activities do not generate any carbon dioxide emissions. The company is also involved in many cooperation projects aimed at reducing the emissions of the entire air traffic sector. Among other things, Finavia participated in the funding of testing and development of Finland’s first electric aircraft.

Case study G indicates, how global and EU level regulation on airports and air traffic has an impact on Finavia’s operating environment and development of the competition. The regulations concerning aviation safety, environmental matters and pricing of services requires continuing investments in new technology and development of service production processes. Finavia continues planning and implementing the multimodal travel centre of the Helsinki-Vantaa Airport.

Case Study 4: Finnair

Finnair is a network airline that specialises in passenger and cargo traffic between Asia and Europe. Finnair also offers package tours under the Aurinkomatkat-Suntours company and Finnair Holidays brands. Finnair carried 14.7 million passengers in 2019. The cornerstone of Finnair’s strategy is the company’s competitive geographical advantage, which enables the fastest connections in the growing market of air traffic between Asia and Europe.

Finnair’s vision is to offer its passengers a unique Nordic experience. Its mission is to offer the smoothest and fastest connections in the northern hemisphere via Helsinki and the best network to the world from its home markets. The network business model is based on a broad network that is built around one or a few airports. Finnair’s main hub is Helsinki-Vantaa Airport, from where the company is flying to over 130 destinations in Asia, North America and Europe.

The foundation for the strategy is the high quality and safety of Finnair’s operations, Helsinki-Vantaa’s favourable geographic position, the growing focus markets, the clear goals to increase revenue, the modern fuel-efficient fleet as well as a strong balance sheet. In Table 4 the analysis of the case of Finnair is reported.

| Case Study 4: Finnair | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| Finnair is a network airline that specialises in passenger and cargo traffic between Asia and Europe. Finnair also offers package tours under its Aurinkomatkat-Suntours and Finnair Holidays brands. Finnair carried 14.7 million passengers in 2019. Finnair’s vision is to offer its passengers a unique Nordic experience. Its mission is to offer the smoothest, fastest connections in the northern hemisphere via the Helsinki-Vantaa airport and the best network to the world from its home markets. The network business model is based on a broad network that is built around one or a few airports. Finnair’s main hub is the Helsinki Airport, from where the company is flying to over 130 destinations in Asia, North America and Europe. The foundation for the strategy is in the high quality and safety of the Finnair’s operations, Helsinki’s favourable geographic position, growing focus markets, clear goals to increase revenue, modern fuel-efficient fleet as well as a strong balance sheet. | Analysis A: Sustainable, profitable growth After the accelerated growth phase, Finnair is now targeting sustainable, profitable growth. In 2019, passenger revenue i.e. airline tickets sold to consumers, are the most important revenue source. Last year, they accounted for 80 % of Finnair’s revenue. Approximately 44 % of it is generated by Asian traffic and 40 % by European traffic. Finland and North America both have a share of 7 %. Ancillary and retail revenue accounted for approximately 6 % of Finnair’s revenue. Ancillary and retail revenue increased by 9.5 % and amounted to 176.2 million euros (160.8), reflecting the growth in passenger volumes. On average, customers spent 12 euros per passenger. During the year, particularly advance seat reservations, service charges, extra luggage and in-flight sales were the largest ancillary categories. Analysis B. Asia routes Direct market capacity between Finnair’s Asian and European destinations grew by 4.5 %. Finnair’s capacity growth was focused on Hong Kong and on Japanese routes. Demand from Europe to Asian destinations, especially to Hong Kong, softened during the period. In Asian traffic, Finnair’s market share increased to 6.0 %. Analysis C: Joint businesses Joint businesses strengthen Finnair’s market position, reduce the risks related to growth and make a significant contribution to Finnair’s revenue. Customers can provide more route and pricing options whereas, for airlines, joint businesses are a way to gain benefits typically associated with consolidation | Passive: Not very passive. Reactive: The updated strategy for the period of 2020–2025 will implement five focus areas: Network and fleet, Operational excellence, Modern premium airline, Sustainability as well as Culture and ways of working. Active: Finnair’s ability to operate its network safely and punctually from one of the world’s northernmost air traffic hubs is integral to value creation. The transfer of passengers, baggage and cargo to connecting flights is ensured through efficient processes and close cooperation with airport authorities. Risk-averse: Not very risk-averse. Finnair engages in closer cooperation with certain One World partners through participation in joint businesses, namely the Siberian Joint Business (SJB) on flights between Europe and Japan, and the Atlantic Joint Businesses (AJB) on flights between Europe and North America. Risk neutral: The location of Helsinki-Vantaa airport gives Finnair a competitive advantage since the fastest connections between many European destinations and Asian megacities fly over Finland. Risk lover: New route openings to China show risk-taking and strategic thinking. |

Case study analysis A indicates how Finnair’s business is cyclical in nature, and how in addition to long-term mega trends, it is heavily influenced by external factors. In 2019 Finnair is operating with its new strategy and aiming at the growth in line with Asian markets. A central objective for sustainable profitable growth is to grow cost-effectively, allowing us to maintain our healthy balance sheet and cash flow. 2019.

The continuing impact of global uncertainties, such as the Brexit process and the US-China trade war, was reflected in operations in 2019, particularly affecting cargo. The traffic grew at a slower pace than in the comparison period between Asia and Europe, whereas Finnair’s main markets still produced solid demand growth in 2019. Finnair´s competitors’ capacity reductions, especially on some Nordic routes and from Finland to the Mediterranean, had a beneficial effect on the competitive situation in European traffic.

Case study analysis B indicates that sustainability and endeavours to reduce emissions are at the heart of the company´s strategy. Finnair has committed to long-term carbon neutrality. Finnair is carrying out significant investments of approximately 3.5–4.0 billion euros to substantially reduce our emissions and enable profitable growth. Above all, its investments are aimed at the renewal of a narrow-body fleet to make it more fuel-efficient, economic and environmentally friendly.

Case study analysis C shows that Finnair´s aim is to be a modern premium airline, and its new strategy also includes investments in a premium economy travel class. Combined with a growing service selection and the different pricing tiers of our travel classes, the introduction of premium economy will allow travellers to customise their journeys in more diverse ways than before.

Case study analysis D indicates how Finnair is investing in developing digital services that enable a smooth travel experience and allow customers to tailor the way they want to travel.

Case study analysis E shows that Finnair is investing in customer experience which has played a central role earlier and in the future in the company´s operations. Finnair’s Net promoter score of 38 compares well with the peer group of airlines. Also, in the annual Skytrax survey, customers chose Finnair as the best airline in the Nordic region for the tenth consecutive time.

Case study analysis F shows that the Finnish business environment – and especially Lapland – has also emerged as an attractive travel destination thanks to the determined cooperative efforts of various parties.Finnair believes that Finland as well as the Nordics will also attract passengers in the future.

Case study analysis G indicates that Finnair is a glocal company. Finnair acknowledges its importance for the local economy. Tourism has become a prominent employer in the Nordic region and air travel an enabler of new businesses. Last year was strongly characterised by increased consciousness and public discussion concerning climate change, which also appeared as a major item on the political agenda.

Case Study 5: Scandic Hotels

In Table 5 we have summarised the case analysis of Scandic Hotels. On a general level, the Scandic Hotel group has the largest and widest hotel network and hotel concept portfolio in the Nordic market. Scandic runs operations under a single, full-owned brand that is clearly the best-known brand in the Nordic hotel market. Scandic has hotels in about 130 locations, with the capacity of 57,358 rooms in operation and under development at 283 hotels.

Scandic´s vision is to be a world-class Nordic hotel company. Its mission is to create great hotel experiences for many people. Scandic’s strategy is to grow profitably by taking advantage of the growing demand for hotel experiences in the Scandic’s markets with a leading hotel portfolio and a customer-focused approach. The company´s strategic focus is to constantly develop its customer offering, optimising distribution and profitability. All areas of operation shall be characterized by a sustainable approach and conducted with values that contribute to committed and motivated employees. Strategically, the Scandic hotel group believes in a holistic hotel experience. In Table 5 the analysis of the case of the Scandic hotels is reported.

| Case Study 5: Scandic Hotels | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| Scandic has the largest and widest hotel network in the Nordic market. It runs operations under a single, fully-owned brand that is clearly the best-known brand in the Nordic hotel market. Scandic has hotels in about 130 locations, with 57,358 rooms in operation and under development at 283 hotels. Scandic´s vision is to be a world-class Nordic hotel company. Its mission is to create great hotel experiences for the many people. Scandic’s strategy is to grow profitably by taking advantage of the growing demand for hotel experiences in Scandic’s markets with a leading hotel portfolio and a customer-focused approach. The strategic focus is to constantly develop customer offering, distribution optimising and profitability. All areas of operation shall be characterized by a sustainable approach and conducted with values that contribute to committed and motivated employees. Scandic believes a holistic hotel experience. | Analysis A: Profitable growth and business crash The competitivity and competition edges of Scandic have been significant in the Nordic markets. Scandic has been successful to increase its market share all over in the Nordic countries. Analysis B: Scandic has spread systematically its hotel network in the Nordic market. It has gradually made very good business results. Analysis C: Scandic has crystallised its brand strategy and succeeded to create the best-known brand in the Nordic hotel market. A very visible brand among business travellers pays off. Analysis D: The Scandic has had a very positive cash flow. It has increased its investments in the Finnish main cities. Pay-back time plans may be challenged by the COVID-19 crisis. On the other hand, recovery can be fast if/when the vaccine will be invented. | Scandic saw signs of declining sales at the end of February. It acted rapidly and forcefully to cut costs and protect cash flow. It created a demanding process to lay off or terminate the employment of so many team members. Active: During the first two months year 2020, Scandic saw positive sales development with an increase of slightly more than 2 % for comparable units, driven among other things by strong sales in Finland. From the end of February, occupancy at the Scandic’s hotels, however, began to fall due to the coronavirus. In March, sales dropped about 47 % for comparable units. Risk-averse: As a result of the work to secure Scandic’s financing, the Board of Directors has decided to postpone the publishing of the company’s Annual Report for 2019 from April 30 to May 25, 2020. Risk neutral: As a large part of Scandic’s leases is revenue-based, the cost base is flexible while the company shares interests with the property owners since higher revenues for Scandic mean more rental revenue and property value for the landlords. Internationally, many large hotel chains instead prioritise a franchise model where they only control the brand while operations are run either by a specialized management company or by the property owner itself. And some hotel companies have a integrated model where the property owner is responsible for both operations and the brand. Risk lover: The hotel industry can be divided into three different parts: property ownership, hotel operation, and brand and distribution. Scandic has chosen to focus on a model with long-term lease agreements with property owners where the Scandic maintains full responsibility for the brand, hotel operations, and distribution. This is the dominant model in the Nordic markets and Germany. |

Case study analysis A indicates that the Scandic group is focused on the Nordic countries and the company wants to provide a full set of hotel and hospitality services to its customers. The company has diagnosed its Nordic market position professionally because it has reached a very strong position in its market area and hotel services segment. Key prescriptions are: (1) to have a model with long-term lease agreements (2) to have with property owner’s full responsibility of the Scandic brand, and (3) to have the best-known brand in the Nordic hotel market.

Case study analysis B indicates that the company has at least a middle-range time horizon in its strategy. The long-run vision is linked to keeping its brand value high. This kind of vision statement is quite general, and not very much focused on the customers of Scandic.

Case study analysis C indicates that the company has performed both qualitative and quantitative trend analyses. Trends like brand responsibility and holistic hotel experience are adopted by the Scandic hotel group. In general, it follows mainstream trend analyses, which underline corporate responsibility, sustainability challenges and the importance of the markets in the Asia-Pacific market.

Case study analysis D indicates that the company has performed foresight analyses and strategic conversations, but what actually was done inside the company, is not reported broadly in its recent business documents. This communication strategy can be motivated by strategic adoption of high confidentiality of business secrets.

Case study analysis E (foresight activity level) indicates that the company has passive, reactive and proactive elements in its business model. Not all business model elements are proactive. Inside the company, there are assumptions that some issues in the business environment are quite stable.

Case study analysis F (company´s attitude to risk management) indicates that the company has diversified its risk portfolio. There are elements of a business model which can be linked to risk-averse, risk-neutral and risk lover behaviour.

Case study analysis G indicates that the Scandic hotel group mainly has a growth-oriented business model. The company wants to deliver profits to its owners.

Case Study 6: NoHo – Nordic Hospitality Partners

NoHo Partners Plc is a Finnish restaurant group. It operates approximately 250 restaurants, bars, pubs, nightclubs and entertainment centres in Finland, Denmark and Norway and in the future, other parts of Northern Europe.

The vision of NoHo Partners is to be the most significant restaurant company in Northern Europe. (NoHo 2020a; 2020b.) The name communicates the key goals, opportunities and strengths of the Group. Nordic emphasises the Group’s future growth market, Northern Europe, as well as Nordic quality, which is appreciated and attractive worldwide. Hospitality reflects the NoHo Partners’ desire to expand beyond conventional restaurant operations, for example to large spectator events and new digital sales channels. Partners, or the partner model, is the cornerstone of the Group’s operations and its key competitive advantage. (NoHo 2020a.).

NoHo is listed on the NASDAQ Helsinki. It is the first Finnish listed restaurant company. It has grown strongly throughout its history. In 2018, the NoHo Partners Plc’s turnover was MEUR 323.2 and EBIT MEUR 7.2. (NoHo 2020a.)

The key success factors influencing the group’s earnings and growth in January–December 2019 were the discontinuation of the labour-hire business, the progress made in the restaurant portfolio reorganisation programme and completing the short-term profitability programmes, the opening of new restaurants, concept reinventions and investments in international business.

The restaurants are NoHo Partners’ largest business sector, in which the company meets the growing demand for, and interest in, eating out with its extensive brand portfolio and partner operating model. The market for fast dining is continuing its rapid growth, driven by urbanisation, new ways of spending time and digitality.

The company is also positioning its portfolio on the experience market with increasing concept variety. With traditional nightclub business representing approximately a third of the turnover of the Nightclubs and Pubs & Entertainment unit, the company is simultaneously renaming the unit to Entertainment Venues.

NoHo´s international restaurant business continued its strong growth throughout the year 2019. Its annual turnover was approaching the MEUR 50 milestone. It aimed at profitable growth and productivity by acquiring new units. At the back end of 2019, NoHo Partners prepared for future growth by defining its portfolio choices as well as investing in the optimisation of its units.

The measures to achieve the profit turnaround are reorganising the units by getting rid of non-profit units, implementing purchase and procurement synergies, reorganising administration and strengthening the operative management. (NoHo 2020a, 2020b.) In Table 6 the analysis of the case of the No-Ho Partners is reported.

| Case study 6: NoHo – Nordic Hospitality Partners | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| NoHo Partners Plc is a Finnish restaurant group. It operates approximately 250 restaurants, bars, pubs, nightclubs and entertainment centres in Finland, Denmark and Norway. NoHo is the first NASDAQ Helsinki listed restaurant company. It has grown strongly throughout its history. In 2018, the NoHo Partners Plc’s turnover was MEUR 323.2 and EBIT MEUR 7.2. The key success factors influencing the Group’s earnings and growth in January–December 2019 were the discontinuation of the labour-hire business, the progress made in the restaurant portfolio reorganisation programme and completing the short-term profitability programmes, the opening of new restaurants, concept reinventions and investments in international business. The name derives from the words ‘Nordic Hospitality Partners’, which communicate the key goals, opportunities and strengths of the No-Ho Group. Nordic emphasises the Group’s future growth market, Northern Europe, as well as Nordic quality, which is appreciated and attractive worldwide. Hospitality reflects The NoHo Partners’ desire to expand beyond conventional restaurant operations, for example to large spectator events and new digital sales channels. Partners, or the partner model, is the cornerstone of the Group’s operations and its key competitive advantage. NoHo Partners wants to be an interesting partner for passionate professionals. The Group has a significant foothold in Finland as well as restaurant operations in Denmark and in Norway and, in the future, other parts of Northern Europe. It is the vision of NoHo Partners to be the most significant restaurant company in Northern Europe. | Analysis A: Aggressive growth, business crash and financial crisis NoHo´s turnover grew almost 30 % to MEUR 272.8 year 2019 (2018 MEUR 209.6). Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) grew by 95 % to MEUR 30.6 (MEUR 15.7). The result of the financial period grew by 1,026.8 % to MEUR 47.7 (MEUR 4.2). Restaurant business (comparable continuing operations) turnover grew by 30 % to MEUR 272.9 (MEUR 209.7). EBIT grew by 725.0 % to MEUR 18.4 (MEUR 2.2). | Passive: NoHo had a record business year 2019. The markets collapsed in March and changed the business operations, strategy and scenarios totally. NoHo, as other restaurant groups were not ready for a business meltdown. Reactive: The company started the financial negotiations and the measures resulted in fixed-term, full-time or part-time layoffs of personnel. Active: Before the virus, NoHo Partners acquired five restaurants on the Norwegian market. Together with Night People Group, the company founded a joint venture that will build new Wallis karaoke bars in Finland. The company launched Finland’s first cloud kitchen restaurant in Helsinki, which will have no customer seating, wherein dishes of different popular restaurants will be handmade for home deliveries only. Risk-averse: The new financing will be used for the company’s operations during the crisis and the management of working capital. Risk neutral: The company estimates that its monthly turnover during the state of emergency will be over EUR 1 million and monthly expenses will be approximately EUR 2–3 million per month, depending on the ongoing lease negotiations. Risk lover: NoHo Partners Plc had an aggressive strategy and growth was thought to do by loans. For example, it had a vision for the next few years to expand the Friends & Brgrs concept into a national chain of 30–50 restaurants. |

Case study A shows that the NoHo Group has had a significant foothold in Finland and it wants to develop as well as its restaurant operations in Denmark and Norway and, in the future, other parts of Northern Europe. It has the vision to be the most significant restaurant company in Northern Europe.

Case study B shows that 2019 was a successful year judging by many indicators. NoHo’s strategic choices enabled to turn the profitability of many operations to a good level. It successfully trimmed and sharpened the restaurant portfolio to a more sustainable shape and started to lay the foundations for future growth in the Nordic countries. It gave up its own labour-hire business and started to create future owner-value for a company as the majority shareholder of the Eezy Plc, the second-largest company in the staffing service sector. At the end of 2019, ownership of the Eezy constituted NoHo nearly MEUR 50.

Case study C indicates that in the last quarter 2019 of NoHo’s restaurant business was good. Its operative model has introduced the desired cost flexibility to fluctuations in demand.

Case study D shows how the company invested in new digital systems, which improves productivity. The Eezy M(ergers) &A(cquisitions) transaction improved profitability and cash flow. The company also refinanced its operations in the second half of 2019 by means of more sustainable financial agreements, and in the early quarter of 2020, it announced to redeem the hybrid loan taken out in spring 2019 ahead of schedule.

Case study E shows how the company looked forward full of confidence. At the offset, the prospects for the year 2020 were materially stronger than a year ago. The Finnish restaurant business was waiting to perform well.

Case study F points out that the economic forecasts and global phenomena brought some uncertainty to the operating environment, but the belief and confidence in the sustainable development of operative operations were strong.

Case study G shows, how the company can react quickly to changes. It announced negotiations in accordance with the act on co-operation within undertakings on 13th March 2020 and their rapid progress on 18th March 2020. NoHo reported that due to the sudden change in the circumstances of the pandemic and the recommendations and orders issued by the authorities and the Finnish Government, the company had made a decision concerning layoffs without prior co-operation negotiations. The layoffs were thought to be temporary, with a duration of 90 days at most, and concerned all of the NoHo Group’s personnel in Finland, a total number of approximately 1,300 employees. (NoHo 2020c.)

The company estimated that its monthly expenses during the state of emergency will be approximately EUR 2–3 million per month, depending on the ongoing lease negotiations. The situation on 5th May 2020 was that it negotiated rent relief until the end of May for approximately 70 % of our leases. Negotiations concerning rent for the month of June will continue when the Finnish Government’s plans concerning the lifting of the restrictions are confirmed. (NoHo 2020c.)

NoHo Partners reassessed its strategy focusing fully on managing costs and cash flow as well as financing arrangements in order to ensure that its readyness to continue business operations as quickly as possible after the coronavirus crisis. The time for reassessing the company’s strategy will be once the crisis stage has been survived and business has been resumed.

Case Study 7: The future-oriented strategy of Lapland´s tourism

In Lapland, the tourism strategy is a developing plan and road map and shared expression of many stakeholders. It is built for four years. The strategy offers guidelines and vision for destinations, SMEs, experience and product developing and managing. It gives guidelines for public funding and tourism research and education.

The tourism vision is Lapland aiming to be a wise, year-around, sustainable and original travel destination. All the tourist strategies from 1980 to 2020 has emphasised products, services and experience and year-round activities. In Lapland, the THE cluster has tried to increase overnight stays, direct flight connections and effectiveness of road connections.

The strategies have been grounded on theme-based development (nature, wellness, culture, Christmas and winter products). The destinations and companies have tried to develop summer products but not succeeded in getting tourism volumes. On the contrary, the amount of flights has decreased. The developing of summer travel was based on utilising the tourism potential of national parks.

The Lapland tourism strategy is a vital part of regions business strategies. Table 7 reports the analysis of the case of the Lapland´s tourism strategy.

| Case study 7: Lapland tourism strategy | Foresight analyses (A, B, C and D) | Expected management approach and business model (E, F and G) |

| The Lapland tourism strategy is a developing plan and road map and shared expression of many stakeholders. It is built for four years and offers guidelines and vision for destinations, SME companies, experience and product developing and managing. It gives also guidelines for public funding and tourism research and education. The tourism vision is aiming to be a wise, year-round, sustainable and original destination. All the tourist strategies from 1980 to 2020 have emphasised products, services and experience and year-round activities. The strategies have been grounded on theme-based development (nature, wellness, culture, Christmas and winter products). The developing of summer travel has based on utilising the tourism potential of national parks. The Lapland tourism strategy is a vital part of regions business strategies. | Analysis: Sustainable growth Tourism in Lapland has increased to record high numbers in recent years. Lapland´s goal is to get five million registered overnight stays yearly. Travel incomes are expecting to increase 1.5 billion euros by 2030 and employment in tourism services by a two-fold to 10 000 man-years by 2030. The volumes of international travellers have to grow to 50 % of all overnight stays. Destinations are aiming to get more direct, international flights and rail connections. The year-round nature of tourism, challenges of public transportation, and improvement of the service infrastructure are important issues that must be resolved to create sustainable growth. The key development efforts focusing on tourist centres and tourism zones. DMO´s, specially Rovaniemi, Levi and Ruka, has promoted the higher profile of tourist centres. | Passive: Tourism has grown mainly on wintertime. The marketing strategies have failed to get tourists on off-season from May to November. The availability of skilled workers is also an acute problem that can slow down the development of the entire sector. Reactive: Lapland has wanted to be the leading destination for sustainable nature and experience tourism in Europe in 2020, but the tourism volumes have been so quick that it speeds the investments and puts pressure on safeguarding sustainable development. Active: The strategy has been foreign experience, nature and customer oriented and supportive for the operational preconditions of the tourism entrepreneurship. Risk averse: Lapland wants to be different destination. It recognised the hard competition between destinations and it has not hidden its nature-based experiences and Arctic conditions Risk neutral: Seasonal and nature experiences and the safe environment are adding to its attractiveness. It wants to market itself to extreme adventures and also provide wellbeing services. Risk lover: Lapland has been a pioneer in Arctic nature and experience tourism. Lappish tourism can be perceived as a test laboratory for all Arctic and other Nordic countries. |

Case study A indicates realistic strategic goals of tourism in Lapland. It has tried to develop year-round tourism and sales.

Case study B shows how vital accessibility is for developing and growing of tourism in Lapland. There has to be fluent, competitive priced transport connections (flight, train) to Lapland.

Case study C show that destinations and companies have to develop year-round tourism products, services, and experiences.

Case study D indicates that Lapland has a strong tourism image and Lapland appears as an attractive travel destination for existing and new market areas.

Case study E shows that Lapland has invested in quality processes and safety processes, especially for winter tourism.

Case study F indicates how important Finnair and Finavia, the structural fund assets, EU´s operating aid for regional airports and airport infrastructure and start-up support for new routes are for the tourism in Lapland.

Case study G shows that Lapland wants to increase the internationally attractive summer tourism, e-services and experiences for sale. Lapland should find new customer groups and tour organisers.

Conclusions and reflections

This case study program of the Finnish THE cluster indicates that the differences between the Finnish tourism strategy, which is composed by the Finnish authorities, by business strategies by international companies and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, is the influential driving force as such. It has a national, political and economic role to counsel tourism policy, strategic plans and also guide scenario building processes. The tradition is the same all over the world, where the state is in charge of strategic foresight. Public-private partnership is one key element of tourism foresight and strategy planning in Finland.

The tourism industry in Finland is more operationally oriented, interactive and has a short-run perspective. The strategic goals are aiming for active business and turnover growth from key international markets. The companies´ strategic foresight thinking is concerning the competitors, partners, competitivity and competition edges. This is not a surprising finding but indicates less emphasis on strategic and visionary planning in the tourism business. Tourism marketing organisations (Visit Finland, the authorities of Lapland) are also aiming at new tourism and hospitality markets, innovative products and services.

The case study program indicates how foresight and risk thinking is simplified during times when business is steadily growing. It is easy to see growth from new customer segments and new business areas, if THE organisations do not see any weak signals or wild cards to change current strategy and offerings.