Foreword

XIII Annual conference of The European Sport Economics Association (ESEA) will be held in Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences Pasila campus during the last week in August 2022. This Book of Abstracts includes all accepted papers submitted for the conference. All articles have been blindly evaluated. The conference has been postponed twice from August 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemia crises.

The conference includes a nice package of various themes in sport economics including professional sport leagues, willingness to pay, coaching, European football, and judge biases, among others. The themes capture areas in sport economics that scholars consider important. Surprisingly, the effects of COVID-19 are not widely discussed. Perhaps we must wait until we are able to say something on that topic.

The local organising committee is mainly based on persons working in Haaga-Helia’s Malmi campus, thank you Heidi, Tarja and Sari! Moreover, the ESEA Board has gone systematically through the conference design and provided detail comments on obscurities in the plan. Thank you!

As regards my own role, the overall structure of the conference and the book of abstracts is designed by myself. However, without the help and guidance of local organising committee and ESEA Board the conference would have not taken place.

On behalf of the local organising committee

August 2022

Seppo Suominen, senior lecturer, PhD (Econ)

Preface by the ESEA President

Dear Attendees of the 2022 ESEA Conference,

It is my pleasure to welcome everyone in Helsinki for the 13th ESEA Conference on Sport Economics. After two years without an ESEA Conference in presence, it is great to see colleagues again and talk about sports economics research on Haaga-Helia’s very nice Pasila campus. I appreciate that the group of attendees is slightly smaller this year because many colleagues and universities still have (to deal with) travel restrictions. Nevertheless, I am confident we will enjoy an interesting conference where we can discuss a variety of sports economics topics in presence.

I would like to extend a sincere Thank You to the Local Organizer, Seppo Suominen, PhD, who has done a wonderful job in organizing this conference and making our stay in Helsinki a pleasant one. The ESEA Board also appreciates his flexibility and patience after the cancellation of the 2020 Helsinki Conference because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the shift in preferences towards a virtual-only conference in 2021.

I would also like to take this opportunity to encourage all conference delegates to submit their conference papers to the Conference Special Issue of the International Journal of Sport Finance (IJSF), ESEA’s official journal. The call for papers will be distributed after the conference. Moreover, I encourage the ESEA Community to support our journal by submitting quality papers and providing reviews.

Yours sincerely,

Prof. Dr. Pamela Wicker

ESEA President

Skill Adoption, Learning, and Diffusion: Evidence from Soviet-style Hockey

- Francesco Amodio

- Sam Hoey

- Jeremy Schneider

Introduction

This paper assesses the impact of an unexpected, industry-wide influx of workers with a new set of skills on incumbent workers. We show that the working style brought about by new workers diffuses within and across organizations. We study the case of the National Hockey League (NHL). From its establishment in 1917 until the late 1980s, the NHL player base consisted mostly of North American players. Soviet players in particular were generally not allowed by their government to compete in North America. With the fall of the Berlin wall and the following dismantlement of the Soviet Union, Russian hockey players were increasingly able to move freely across countries and play in the NHL, which caused an influx of new players in the league. It was clear from international games in the 1980s that Soviet players had a more skilled and less aggressive style of playing hockey in comparison to North Americans (Szymanski & Wieneck, 2020). The purpose of our analysis is to establish the degree to which the Soviet style of play was adopted and diffused among North American teams and players.

Figure 1 provides the empirical motivation for this study. The Figure shows that the aggression effort of NHL players, measured by the average number of penalty minutes per player across games, was on the rise from 1970 until the late 1980s. Starting in 1989, the share of Russian players in the NHL increases from 0 to about 10% at its peak in 2000. At the same time, aggressive behavior on ice decreases dramatically, more than can be accounted for by only the Russian players themselves. This suggests that North American players changed their style of play following the arrival of more skilled and less aggressive Russian players.

Using 50 years of data at the player- game level, we show that (i) the number of penalty minutes per game increases steadily from 1970 to 1989, while decreasing thereafter; (ii) these trends are driven by North American born players while Russian players have systematically fewer penalty minutes per game upon arrival and throughout the post-1989 period; (iii) the number of penalty minutes per game of North American born players decreases systematically with the number of Russian players on their team and on the opposing team. Evidence shows that the hockey style brought about by new players diffuses both within and across teams.

Empirical Strategy

The final aim of our analysis is to identify the extent to which the Soviet playing style diffuses both within and across teams by testing whether North American players’ behavior changes as they play not only along but also against more Russian players. We leverage information at the player-game level, restrict the sample to include only North American players, and implement the following regression specification

Y_ikgt=α+β ST_ikgt+γ SO_ihgt+〖 Z〗_it^’ θ+λ_i+ϕ_t+ε_itgs

where Y_ikgt is the number of penalty minutes given to player i on team k during game g in season t. The main independent variables are ST_ikgt, which counts the number of Russian teammates of player i during game g, and SO_ihgt, which counts the number of Russian opponents faced by player i during game g. The coefficients of interest are β and γ, which capture whether, conditional on an abundant set of time-varying controls (〖 Z〗_it^’), the performance of North American players changes systematically as they play along more Russian teammates or play against more Russian opponents respectively. Season fixed effects (ϕ_t) account for and net out average differences across seasons. We also include the full set of player fixed effects (λ_i), thus identifying the coefficients of the variation in the number of Russian teammates and opponents within players over time.

Main Result

Table 1: Penalty Minutes, Russian Teammates and Opponents

Table 1 reports the coefficient estimates from equation 1. In column 1, we begin by regressing the number of penalty minutes per game over both the number of Russian teammates and Russian opponents. The corresponding coefficient estimates are negative, but not statistically significant. In column 2, we add season fixed effects (ϕ_t) and player fixed effects (λ_i), thus exploiting variation within-season and within-player variation. North American players obtain systematically fewer penalty minutes when playing along and against more Russian players, the corresponding coefficient estimates being significant at the 1% level. These are essentially unchanged when adding a vector of time-varying player characteristic controls in column 3.

Seeing the Whole: Investigating Fans’ Holistic Thinking Tendencies as Driver for Multiple Fan Identity and Decreased Loyalty

- Anton Behrens, University of Leipzig, anton.behrens@uni-leipzig.de

Introduction

While the high demand for team sport related offers among fans used to be taken for granted due to irrational consumption patterns by loyal fans, e.g. in times of poor sporting performance (Koenigstorfer & Uhrich, 2009), recent studies find evidence for a more demanding mindset of team sport fans (Tamir, 2020). For example, some fans tend to follow specific star players (Wu, Tsai, & Hung, 2012) and shift their alliances when the quality of one team sport offer is decreasing. One avenue of research in the field of sport economics and sport management that emerged in the last years focusses on the phenomenon of team sport fans, that are following more than one team (Sun, Chien & Weeks, 2021; Watkins & Cox, 2020). Apparently, team sport demand is not necessarily centered around only one club or franchise and can be manifold. However, until today no empirical study has investigated team sport fans’ psychological differences in thinking tendencies and its effect on multiple fan identity and fans’ behavioral loyalty towards their favorite sport club in order to understand team sport demand patterns.

Theoretical background

In 2007 Choi, Koo, and Choi developed the analytical versus holistic thinking scale. Since then, the construct has been frequently used in marketing research, for example to explain different attitudes towards brand extensions (Monga & Roedder John, 2010) or to shed light on cultural differences in consumption behavior between Asian and Western consumers (Luo, Zhu, Han, 2022). The overall assumption being, that holistic thinking enables consumers to take a broader perspective on brands, markets and consumption environments and therefore helps them to be more open to new experiences, products or brand attributes. In addition, consumers may even switch between multiple identities in different consumption settings (Foreman & Whetten, 2002). Consequently, it is likely that consumers who see the team sport market from a holistic perspective are more likely to follow the sport or league as a whole, rather than fully commit to one club in particular. In other words, holistic thinking should allow them to follow more than one club from a particular sport (Ng, Chen, Ng, & Ng, 2021). Formally:

H1: Holistic thinking increases multiple fan identity.

While the followership of different team sport clubs not necessarily negatively affects the consumption of one of them, it is however likely that interferences occur. While some sports fans may support different teams in different sports from one particular city to express their local pride, other fans’ interest could be centered around one sport only. In this instance fans could either support a professional club and a lower-tier club, or might support one domestic football club and another foreign one, or they might even sympathize with more than one club from the same league, e.g. because they moved from one city to another and hold sympathies for both of them (Collins, Heere, Shapiro, Ridinger, & Wear, 2016). The current study’s focus lays on team sport fans that support more than one club from one particular sport – football. Consequently, there should be some sort of direct competition between consumption intensity and commitment between the different football clubs. This should lead to decreases in behavioral loyalty of the favorite football club if other clubs are being followed, too.

H2: Multiple fan identity decreases behavioral loyalty of football fans towards their favorite club.

Building on H1 and H2, there should also be an indirect and negative relationship between holistic thinking and behavioral loyalty through multiple fan identity.

H3: Multiple fan identity mediates the negative effect of holistic thinking on behavioral loyalty of football fans towards their favorite club.

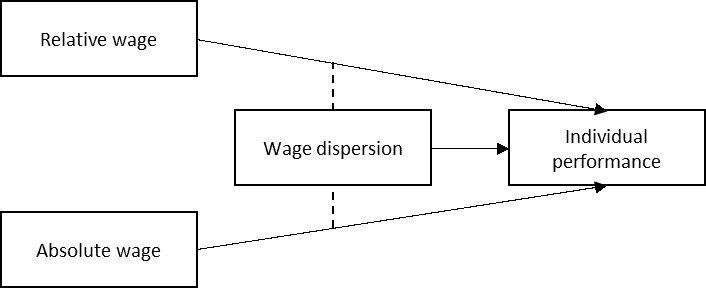

Figure 1. Proposed research model.

Methodology

German football fans serve as research objects. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM) will be used to test the suggested research model.

Expected results

In the current stage of the project the data collection is ongoing. Therefore, the results will be presented at the conference. However, building on our hypotheses we expect the following theoretical and practical contributions.

Theoretical implications

While current studies on ambi-fans or polygamous fandom focus on factual reasons for the decisions to follow more than one club or explain their consumption behavior, this study is the first to shed light on psychological indicators that might affect the likeliness for team sport consumers to follow more than one club and consequently be less committed to one club in particular. Focusing on psychological factors rather than consumption circumstances shifts the focus of scholars in the field and enables us to observe general patterns of consumption in teams sports demand.

Practical implications

Practitioners gain a deeper understanding of team sport consumers and could, for example, segment the consumers based on their thinking styles (e.g. in general team sport consumers that tend to think more holistically and more attached, loyal fans of single clubs). This could help to address the needs of holistic thinkers and analytical thinkers and try to increase their demand in accordance to their overarching mindset.

Cash or Culture: Following the Vein of Olympic Gold

- Michael Barta, Monash University

- Ross Booth, Monash University, Ross.Booth@monash.edu

- Robert Brooks, Monash University

Extended Abstract

This paper examines variations in Medal Tallies at the Summer Olympic Games between top medal earning countries. Using summary statistics and fixed-effects regression analysis, results suggest that country specific Discipline fixed-effects are the main determinants of medal outcomes. It was found that medal event participation had more explanatory power in determining medal outcomes at a given Games than team size. Furthermore, medal event participation could be a measurable source of the host country effect. It is concluded that the structure of a country’s national Olympic body can have significant effects on medal outcomes.

Introduction

Since the establishment of the Australian Sport Commission (ASC) in 1985 under the Australian Sports Commission Act 1989, the agency is now comprised of two separate divisions. Each division is responsible for achieving different key outcomes. Sport Australia (SportAus) is responsible for driving greater population engagement and capability in Australian Sport, and the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) is ‘responsible for building sustainable winning systems for Australian athletes that are measured through consistently producing podium success over multiple cycles, inspiring the next generation’ (Australian Sports Commission 2021).

As outlined by the 2021-25 ASC Corporate Plan, the vison of the AIS is ‘generating a competitive advantage for Australian athlete success at the Olympic, Paralympic and Commonwealth Games; while supporting other sports where our primary focus is enhanced by faster learning and/or where we generate incremental revenue that would justify the effort’ (Australian Sports Commission 2021).

The success factors for the vision of the AIS are:

- Podium Success – Australians consistently winning medals at major international events

- Pride and Inspiration – Australian sporting champions are a positive influence on the community, and

- World-Leading System – Australian high-performance system, is recognized as world- leading.

With the performance criteria being:

- Number of medals and medalists at the Olympic, Paralympic and Commonwealth Games and at International Championships

- The level of positive sentiment from sporting results, athlete conduct and engagement within the community, and

- Sports’ progress against a performance monitoring framework.

As an event, the Summer Olympic Games is the pinnacle of many countries sporting aspirations, including Australia. Since the first modern games run by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in Athina in 1896, the Summer Olympics have grown to be one of the largest cultural events of the world. For the first time in its history, the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Games had every National Olympic Committee (NOC) compete in the Games. At the 2020 Tokyo Games 11,319 athletes competed across 49 Disciplines, in a total of 339 Medal Events with 340 Gold, 338 Silver, and 402 Bronze medals awarded, a total of 1080 in all. Since the first Games, a grand total of 5,121 Gold, 5,085 Silver, and 5,493 Bronze medals have been awarded. Before the 2020 Tokyo Games, the top 10 medal ranking countries had secured 3,412 Golds, 3,086 Silver, and 3,099 Bronze, a combined total of 9,597 medals, 61% of all medals awarded. These countries are; the United States, the Russian Federation, Germany, Great Britain, the People’s Republic of China, France, Italy, Hungary, Australia, and Sweden, with Japan placing eleventh in the historic Medal Tally.

This paper explores the relationship between a country’s national funding towards the Olympics, their participation at any given Games, and their Medal Tally. Furthermore, this paper attempts to determine if there are any country specific or Olympic specific factors that might drive medal outcomes. Additionally, this paper attempts to determine the most accurate measurement of a country’s participation at any given Games. The aim of this research is to provide insight into the AIS, determine if they are meeting their success factors and provide possible guidance into how they could allocate their limited resources. Detailed analysis has been conducted on either specific country’s Olympic programs or broader country demographics that lead to Olympic success. This paper aims to address why inter-country variations in Medal Tallies occur. Given the results of previous research on Olympic success, the hypothesis is that there is a significant relationship between Australia’s Olympic participation, current funding strategy and Olympic success.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews current literature into what drives medal outcomes at the Olympics. Section 3 gives a brief explanation of trade theory and how it may apply to Olympic success. Section 4 describes the data used for estimations. Section 5 introduces the fixed-effects methodology employed. Section 6 provides results and figures of the estimations for medal outcomes. Section 7 is a discussion of the results implications for the AIS. Finally, Section 8 contains concluding remarks and possible research opportunities.

Conclusion

This paper investigated the AIS to determine if they are achieving Podium Success. In doing so, AIS funding data per Sport and Olympic participation was compared against medal outcomes to determine if there was a significant relationship. No significant relationship was found. The same methodology was applied to a similar national body, UKSport, of Great Britain. A significant relationship was found between funding, Olympic participation and medal outcomes. A modified methodology was applied to the historic top medal earning countries to determine if there are any patterns of success between countries. It was found that significant inter-country Discipline fixed- effects were the main cause of variation in medal outcomes between countries. Furthermore, differences in intra-country Discipline fixed-effects were observed to be the main cause of variation in medal outcomes between Disciplines for a given country.

The results confirm what a casual observer of the Olympic Games can tell you. The Japanese are extremely successful in Judo, the Australians and Americans do exceptionally well in Swimming, and the Russians and Chinese will compete for many of the Artistic Gymnastic medals.

The aim of this research was to determine if Australia had a World-Leading System when it comes to sporting success. The research shows that in some parts it does, it also shows that it is possible to do more with less. The research also shows that there needs to be greater care and consideration about where Australia should put their limited resources moving towards the 2032 Brisbane Games, otherwise the results might be the ‘arms- race’ prisoner’s dilemma game as foretold by Humphreys et. al. (2018).

Additionally, this research highlights the important role that the separate national sporting bodies have in determining athlete success in Australia. Further research opportunities exist in determining how Australia has such large and significant inter-Discipline fixed-effects and how other top medal earning countries differ in their Olympic programs.

Reluctant to Move? Salary Penalties for Domestic Players in European Football

- David Berri, Southern Utah University

- Alex Farnell, Maynooth University, alexander.farnell@mu.ie

- Robert Simmons, Lancaster University

- Esperance Yassine Bamba, Southern Utah University

Introduction

A considerable literature exists attempting to identify wage premia and wage penalties for specific groups in professional team sports. For example, the National Basketball Association has increased its hiring’s of foreign-born players over the least 30 years, though evidence of salary differentials for foreign players is mixed.

While North American sports have extensive salary and performance data, all publicly available, attempts to estimate salary premia or penalties by nationality for European football face the dual problems of lack of precise and credible salary data, and thin performance data. Early examinations of European football simply used goals and assists as performance measures, which do not cover contributions of defenders and midfielders. Some studies (Szymanski, 2000; Deschamps and De Sousa, 2021) have worked around this problem by regressing team performance on relative wage bill and numbers or proportions of black players on team rosters. These papers show evidence of discrimination against black players in the 1970s and 1980s. Deschamps and De Sousa also find that, after the 1995 Bosman Ruling which loosened mobility restrictions, pay discrimination remained for just one identifiable group: black non-EU players who faced immigration control restrictions.

Until recently, Italy’s Serie A was the sole source of credible player salary data in European football. Gazzetta dello Sport has published salaries of Serie A players each September since 2008, with authors such as Bryson et al., 2014 and Carrieri et al, 2018 making use of these. The paper closest to ours is Bryson et al., 2014. The authors identified a salary penalty for domestic (Italian) players relative to their migrant counterparts.

Contributions

We extend the work of Bryson et al. (2014) in three distinct ways. First, we have salary and performance data for a much larger sample of players over seven seasons (2013/14 to 2019/20) from five top European leagues: the English Premier League, French Ligue 1, German Bundesliga, Italy’s Serie A and Spain’s La Liga. This offers greater generality of results compared to Bryson et al. who only covered Italy. Second, Bryson et al.’s nationality classification was rather coarse being limited to Italian, non-Italian European Union and non European Union. We extend this classification to explicitly cover the continents of Europe, North and South America, Africa and Asia. Third, although Bryson et al. had a deep set of player performance controls in their model, they did not specify precisely which performance metrics were important in predicting player salary. We make a further contribution by using a richer set of performance metrics from www.whoscored.com, which are matched with our salary data. We then show the most important performance metrics for salary determination within a parsimonious model.

Data

Our assembled dataset gives us information on 3,458 outfield players in the top 5 European leagues over a 7 season period. Goalkeepers are excluded as they have qualitatively different roles and performance metrics to outfield players. This amounts to 10,455 player-season observations. Salary data were purchased by subscription from www.capology.com, where salaries are sourced from surveys of player agents (The salary values for Italy’s Serie A players exactly match the figures published by Gazzetta dello Sport).

We include as explanatory variables various proxies for human capital such as age, and number of career appearances in top 5 European leagues, other leagues and UEFA competitions. We include minutes played in previous season expecting this to be positively associated with salary. Our performance measures include pass completion percentage, average passes completed per game and shots on target per game. All performance measures are taken from previous season to allay potential endogeneity concerns. A team’s ability to pay is proxied by the log of the previous season’s average attendance. We include a dummy variable to denote whether a player switched teams between seasons, with the expectation that most players move to better teams who can pay higher salaries.

Our primary interest is the effect of nationality on player salary, thus, we initially include dummy variables for continent of origin i.e. Africa, Asia, South America, North America and Oceania. We also include a dummy variable ‘Home’, defined as 1 if a player has the same nationality as the league which he is contracted to (i.e. English, German, French, Italian, or Spanish).

Methodology

We start by estimating a standard wage equation (for player i in season t):

Log payit = β0 + β1Ageit + β2Age2it + β3Career appearancesit-1 + β4Performanceit-1 + β4Game timeit-1 + β5Team attendanceit-1 + β6Continenti + Position fixed effects + Season fixed effects + League fixed effects + error

which is estimated with OLS initially. However, log salary shows skewness and excess kurtosis, rendering OLS estimation inappropriate. As such, we run unconditional quantile regression models as applied recently by Carrieri et al. (2018). Note that inclusion of player fixed effects is inappropriate due to their collinearity with nationality. We experiment with alternative variables to capture career appearances and performance.

Preliminary Findings

Age and age squared deliver familiar positive and negative coefficients, respectively. For unconditional quantile regression at the median the turning point in age is 26.5, in line with industry expectations and previous work. Appearances in UEFA competitions, top 5 leagues and other leagues have significant, positive coefficients that reduce in size according to competition status. Perhaps surprisingly, we find no significant effect of national team appearances on player salary. Minutes played in previous season has a positive and significant effect on salary. From the performance statistics considered we find significant effects for pass completion rate, average passes completed and shots on target. This reflects the modern emphasis in football on passing and ball retention.

Season dummies reveal higher salaries from 2016/17 compared to earlier seasons, and league dummies show the ranking of salaries to be England, Italy, Spain, Germany and France, in line with expectations. The ranking of salary by position is forwards, midfielders then defenders again as expected. Players who switch teams tend to earn higher pay.

Of the Home and continent of origin dummies, Home, African and South American deliver significant coefficients. The other continents failed to deliver significant coefficients. Preliminary results for said nationality effects are shown in the table below (t statistics in parentheses).

We observe significant and substantial salary penalties for African players at median and below. South American players earn salary premia from 25th quantile upwards. Interestingly, home players receive salary penalties at median and below yet salary premia emerge at 75th and 90th quantiles. Players in these quantiles tend top be established stars, superstars even at 90th quantile (Bryson et al., 2014). Moreover, leagues and UEFA have introduced quota rules to guarantee a number of roster slots to ‘domestically trained’ or home grown players. This perhaps leads to an outcome where star domestic players earn a salary premium while more substitutable players receive a salary penalty.

Of great interest here is whether home grown players generate enhanced salaries via popularity as well as their performances. This, along with a finer classification of nationality origin e.g. Wester European countries versus Eastern European, as well as the mobility channels for arrival into a given league, will be pursued in further work.

Demand for TV Broadcasts of UEFA Champions League Games in Danish Television – The Impact of Uncertainty of Outcome, Team Reputation, and Superstars

- Oliver Budzinski, Ilmenau University of Technology, Germany

- Arne Feddersen, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

- Philipp Kunz-Kaltenhäuser, Ilmenau University of Technology, Germany, philipp.kunz-kaltenhaeuser@tu-ilmenau.de

Relevance and Motivation

The year 2021 witnessed the outbreak of a fight about the right way of organizing the highest level of European football: while the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) presented their model of a reformed UEFA Champions League (UCL) (UEFA, 2021), a company called A22 (representing a number of high-profile European football clubs) presented an alternative model of a so-called European Super League (ESL) (Wagner et al., 2021). However, there are noticeable conceptual differences between the models proposed by UEFA and A22 and much of the argumentations from both sides focuses on fans preferences. At the core, this addresses the question of drivers of the demand for stadium attendance and TV broadcasts. While both represent a recurrent topic in sport economics, especially the latter drives the commercial business of football: broadcasting revenues represent the single biggest revenue source (Boyle, 2015).

One of the conceptual controversies in the context of premium level football in Europe is concerned with the question whether fans have a stronger preference for (more) games between the top teams (as the ESL proponents argue; Hamilton, 2021) over a broad participation of less well-known clubs representing more of the regions in Europe or vice versa (Solberg & Gratton, 2004). Sports economic theory offers explanations for both views: Superstar effects (Hausman & Leonard, 1997; Lucifora & Simmons, 2003; Berri et al., 2004; Jewell, 2017), local hero and home-win preferences (Brandes et al., 2008), as well as uncertainty of outcome (Rottenberg, 1956; Neale, 1964) considerations affect consumer demand, yet the direction of their effects is ambiguous.

Since theory does not point into an unambiguous direction, empirical analysis of the demand for broadcasts of premier level European team football games is warranted. Due to the trade-off between (i) superstar clubs coming from very few national leagues (England, Spain, Germany, France, Italy) and most superstar players, irrespective of their nationality, playing for these star clubs and (ii) local top clubs from other countries and regions rarely making it into the final rounds of top level tournaments, it is particularly interesting to analyze audience behavior in a country outside the top 5 leagues because here the local top club is likely to not or only rarely qualify for a top-tier pan-European competition. While fans in top-5-league countries will witness some domestic clubs compete in each of the proposed models, Danish fans – as an example for a non-top-5-league country – are more likely to “lose” their domestic clubs in the ESL scenario. Therefore, it is particularly interesting to know how Danish broadcast demand changes if superstar clubs play against each other, local heroes are present, and uncertainty of outcome changes. This can give indication whether fans care more about top games or more about local heroes.

Related Literature

The literature regarding the determinants of demand for sports has been dominated by studies of game attendance at sporting events (for comprehensive reviews, see Borland & Macdonald, 2003; Szymanski, 2003; García & Rodríguez, 2009; Schreyer & Ansari, 2021). For a long time, studies of the demand for TV broadcasts have been underrepresented in the literature (strongly due to limited data availability). Although many determinants are theoretically and empirically identical, it can be assumed that some determinants of TV demand differ distinctly from stadium attendance. One key example would be differences in consumers’ preferences for outcome uncertainty and wins of the home team (Forrest, Simmons, & Buraimo, 2005; Coates, Humphreys & Zhou, 2014). So far, the empirical evidence on the demand determinants of TV audiences is still limited, although growing during the last couple of years. Early studies on television demand for live sports include Kuypers (1997) and Forrest, Simmons, and Buraimo (2005). These studies were followed, inter alia, by Johnsen and Solvoll (2007), Weinbach and Paul (2008), Paul, Wachsman, and Weinbach (2011), Alavy et al. (2007), Nüesch and Franck (2010), Di Domizio (2010), and Feddersen and Rott (2011). Most of the existing research focusses on either North-American Major Leagues (Weinbach and Paul (2008); Tainsky, 2010) or top tier domestic leagues in European football (Forrest et al., 2005; Buraimo & Simmons, 2009, 2015; Perez et al., 2017). This paper contributes to the literature by providing a novel setup for the analysis of the demand for TV broadcasts in a European country which does not have a strong domestic league or strong clubs on the European level. The fact that the Danish champion does not qualify for the UCL group stage in many seasons (but in some) allows us to analyze the impact of superstar teams (e.g., Real Madrid, Manchester United, Juventus, Bayern Munich, PSG) as well as the local hero clubs (i.e., Danish clubs). Furthermore, the absence of a strong local hero club offers an interesting setup to analyze the effect of outcome uncertainty.

Methodology

We analyze television ratings of live broadcasts of UCL games in Denmark. The data is collected by Kantar Media, which uses a representative panel of 1,200 Danish households to estimate the nationwide television ratings. Our analysis is based on the average number of TV viewers of UCL matches with an age of 3 years or older from 2006/07 to 2018/2019.

We estimate a semi-logarithmic OLS regression model where the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the average TV audience of UCL matches broadcasted in Denmark. To capture time-invariant heterogeneity in the participating teams and effects across seasons, fixed-effects are included. We use win probabilities based on betting odds as a proxy for the uncertainty of outcome as it is frequently used in the literature. The model includes variables on the participating clubs such as their overall market value, the number of superstars on their roster, their UEFA 5-year-coefficients, and whether they are a Danish club or not. Furthermore, we control for weather (precipitation and temperature) as well as the progression of the tournament (round of sixteen, quarterfinal, semi-final, final).

Results and Conclusions

We find that the presence of superstar clubs as measured by accumulated market value of players increases broadcast audience significantly. Team quality as measured by UEFA 5-year-coefficients as well as the presence of high-earning superstar players lack a significant effect. Matches including Danish clubs increase TV audiences , whereas the number of Danish players on a team’s roster (local hero players) do not. Uncertainty of outcome increases TV demand in our model, supporting the UOH for TV audiences and furthering the discussion around diverging preferences between stadium attendance and TV demand. The estimated coefficients for the probability of a home win and its squared value are statistically significant and indicate an inverse U-shape relationship, Which is in line with the OUH.

Our findings support the hypothesis that fans prefer seeing games between superstar clubs, while they also provide evidence for a preference of the presence of local clubs in the competition. Interestingly, the status of the club matters more than the status of the players. Therefore, based on our preliminary results, the conclusion might be drawn that a competition design with many games between foreign non-superstar clubs is uninteresting for fans; however, the absence of local clubs seems to have a negative effect on TV ratings.

Should Organizing Premier-Level European Football Be a Monopoly? And Who Should Run It? – An Economists’ Perspective

- Oliver Budzinski, Ilmenau University of Technology, Germany, oliver.budzinski@tu-ilmenau.de

- Arne Feddersen, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Introduction

In April 2022, twelve clubs agreed to form a mid-week pan-European football club competition, the Super League, which would be in direct competition to the Champions League (UCL) organized by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). Besides a strong public backlash from football fans, UEFA, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the English, Spanish, and Italian football associations as well as the respective league organizations have immediately opposed and publicly condemned the project. In a subsequent press release, the above-mentioned governing bodies of football announced that the twelve involved clubs will be banned from playing in any competition at domestic, European or world level organized by those governing bodies. Furthermore, the players from the twelve ESL clubs were threatened that they could be denied the opportunity to represent their national teams.

In late April 2021, the clubs and company (A22 Sports Management) behind the Super League received legal protection from a Spanish commercial court. In mid-May 2021, the concerned court referred a preliminary question to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Here, the question to be clarified is whether FIFA and UEFA have violated articles 101 and 102 of the TFEU and especially if UEFA’s monopoly position as (1) the solely governing body, (2) the disciplinary institution, and (3) income distributor is illegal according to European Union competition law. Furthermore, the court also investigates a potential abuse of a dominant position by UEFA through (a) actions to press the involved clubs to abandon the project, (b) the issuing sanctions, and (c) threatening to exclude the involved clubs from all UEFA competitions.

The aim of this analysis is to provide insights into the question whether UEFA (or other premier-level governing bodies in sports) can take on the three roles as sole regulator, operator, and gatekeeper at the same time without infringing European competition law.

Structure

In economics, monopolies are associated with severe consumer (fan) welfare loss and massive dynamic inefficiencies. Therefore, effective competition in every market is the generally preferred organization of commercial activities and, subsequently, the main goal of competition law and policy. Yet, there may be situations where a single supplier of a good may exceptionally be superior to competition. Organizing premier-level sports is often viewed to be such an exception – as in the EU with the pyramid structure of sports associations governing professional (and commercial) sports (as described, inter alia, in the EU White Book on Sports).

In the first part of this chapter, we review this assertion from a modern economics perspective. What are the economic arguments in favor of the pyramid structure, what are those against it – and how should they be balanced? What do the manifold empirical studies tell us about the relevance of the pros and cons? In doing so, we unbundle the monopoly governance by identifying specific tasks that require a single supplier/organizer and those that can be subject to market competition.

In the second part of the paper, we go beyond these theory-driven categorization by looking into the checks and balances that are necessary for a workable, efficient, and fair use of the inevitable monopoly power. This includes identifying areas which need to be separate and independent from each other to avoid and balance conflicts of interests. Furthermore, we discuss for the identified monopoly areas who should run them in order to maximize social and consumer (fan) welfare.

Theory and Methods

This paper is a classical competition policy paper, i.e., it applies modern state-of-the-art insights from industrial/sport economic theory and empirical evidence from the literature to assess, evaluate, discuss, and propose competition rules and their application/enforcement. The approach in this paper can be classified as institutional economics as well as law & economics. The analysis is based on the extensive literature on competition policy in sports markets but is also looking at insights from similar cases from other markets (e.g., media markets, online retail platforms).

Results and their Relevance for Sports Competition Policy

Our analysis yields relevant implications for the application of competition law to premier-level sports leagues. In the light of our results, suggestions are derived to (i) revise the three-step-procedure in European competition policy towards sports markets (as laid out by the European Commission) as well as (ii) the case judgments defining the borders of sports associations’ monopoly power (like the FIA case, the Premier League case, the UEFA case, and the Bundesliga case – as well as comparable cases on national level, esp. Germany, Great-Britain and France). Our results are relevant for the pending competition law case in European football “Super League vs. UEFA”. However, besides this concrete case, our analysis is providing insights for competition policy in sports markets and its enforcement and it will be helpful for the future design of the governance of premier-level sports leagues and, thus, for league organizers and managers.

Gender differences in choking under pressure: Evidence from alpine skiing

- Christoph Bühren, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany, christoph.buehren@ruhr-uni-bochum.de

- Martin Gschwend, University of St. Gallen, Switzerland

- Alex Krumer, Molde University College, Norway

Motivation and purpose of the paper

The purpose of our paper is to investigate whether having a compatriot course setter influences performance of professional alpine skiing racers and to examine whether there are any gender differences in this response. The desire to win likely depends on the perceived importance of the competition and the belief about one’s likelihood to win it. We analyze gender differences in performance under pressure in an unusual clean setting, in which the importance of the competition and the expectation about one’s performance are exogenously manipulated. We compare the performance in the first runs of Slalom and Giant Slalom to the more important second runs in these competitions. Moreover, we distinguish between runs that are set by the own team captain and runs set by the captain of another team. It should be an advantage to compete on a course set by the own team captain, which is likely to induce high expectations. Finally, we compare the results in the most technical and, thus, skill-based discipline (Slalom) to the most effort-based discipline in our sample (Super Giant Slalom) and to a discipline in between those two (Giant Slalom).

Theoretical background

Cohen-Zada et al. (2017) find that choking under pressure, i.e. performance decrements despite high incentives to perform well, is more prevalent among men than women. The authors argue that for men it seems to be too important to win (see also Niederle and Vesterlundt, 2007).

Böheim et al. (2016) replicate the result of Grund et al. (2012) that male basketball teams increase their risk-taking at the end of the game. In contrast, the authors observe that female teams (from the Women’s National Basketball Association) reduce their risk-taking at the end of the game. When trailing, Böheim et al. (2016) find some evidence that male teams reduce their chances to win with this strategy, while female teams increase their chances.

Bozhinov and Grote (2008) find that male, as well as female, volleyball players reduce their serve errors in crunch time compared to the rest of the game. However, both genders also serve fewer aces in crunch time. Moreover, men serve less jump serves and more average serves – as opposed to good serves that restrict the attack possibilities of the opposing team. As a result, male and female players lose more points on serve in crunch time compared to the rest of the game – they choke under pressure. The effect size of crunch time on losing more points on serve is slightly larger in the men’s than in the women’s sample.

Further evidence that the level of risk-taking in pressure-situation can be suboptimal comes from Paserman (2010). The author finds that tennis players inefficiently reduce their risk-taking at very important points. By just looking at unforced errors in tennis, Paserman (2007) concludes that women choke more under pressure than men. The estimates of the game-theoretic model in Paserman (2010), however, suggest that especially men’s performance decreases under pressure because they play these points too safely. This interpretation seems to contradict the findings of Charness and Gneezy (2012) but is in line with Cohen-Zada et al. (2017).

Empirical description

We collected data from the official website of the FIS on all men’s and women’s Slalom, Giant Slalom, and Super Giant competitions that took place in the World Cups, World Championships, and Olympic Games for the seasons from 2001/02 to 2017/18. The final dataset consists of 442 men’s and 445 women’s competitions. The data include performances of 1,196 men and 956 female racers. In men’s competitions, there were course setters from 17 countries; in women’s competitions from 16 countries. Overall, our data consist of 40,150 races among men and 36,968 races among women.

We use a racer per season fixed effects model that allows us to compare the performance of racers when they compete on the course that was set by their compatriot to the performance of the same racers when they compete on the course that was not set by their compatriot. Our main variable of interest is a dummy variable that receives the value of one if a course setter is a compatriot of a racer in the respective run. To estimate the possible effect of having a compatriot course setter on performance in alpine skiing, we have a set of four outcome variables. The first two are dummy variables that receive the value of one if a racer did not finish the first run or the second run. The third outcome variable is a dummy variable that receives the value of one if a racer finished the competition in one of the top three positions. Our last outcome variable is the number of World Cup points that a racer achieved in the respective competition.

Main results

In the men’s competitions, we see that having a compatriot course setter has no significant effect on the probability of failing to complete the first run in all three disciplines. Surprisingly, we find that having a compatriot course setter increases the probability of failing to complete the second run by 4 percentage points in Slalom. This result suggests that having a compatriot course setter in the second run of Slalom competitions not only does not help, but it even impairs the performance of the racers. However, we find no significant effect in Giant Slalom. Finally, we observe no significant relationship between having a compatriot course setter and being on the podium or achieving World Cup points in the men’s competitions.

In the women’s competitions, we also find that having a compatriot course setter has no significant effect on the probability of failing to complete the first run in all three disciplines. However, we observe that having a compatriot course setter decreases the probability of failing to complete the second run of Slalom competitions by 3.8 percentage points. This result, in contrast to our finding for male racers, suggests that having a compatriot course setter in the second run of Slalom competitions enhances the performance of female racers. Even though we find no significant effect on the probability of being on the podium, having a compatriot course setter has a positive effect on the overall performance in terms of women’s World Cup points in Slalom competitions. More specifically, female racers whose compatriot sets the course in the second run of Slalom competitions are expected to gain 1.6 World Cup points more.

We explain these results by gender differences in choking under pressure in skill-based tasks. Our findings complement the results of Ariely et al. (2009), Cohen-Zada et al. (2017), and Harb-Wu and Krumer (2019). Having a compatriot course setter should be an advantage but also sets expectations to perform well, which seems to induce inefficient levels of risk-taking among men in crucial stages of a competition.

Professional Sporting Events Increase Seasonal Influenza Mortality in US Cities

- Alexander Cardazzi, West Virginia University

- Brad R. Humphreys, West Virginia University

- Jane E. Ruseski, West Virginia University, jeruseski@mail.wvu.edu

- Brian P. Soebbing, University of Alberta

- Nicholas Watanabe, University of South Carolina

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down sporting events worldwide. Local policy makers and league officials face important decisions about restarting play, especially in pro-fessional leagues that draw large numbers of spectators. We analyze the impact of professional sporting events on local seasonal influenza mortality to develop evidence on the role played by sports in airborne virus transmission. Results from a difference-in-differences model applied to data from a sample of US cities that gained new profes-sional sports teams over the period 1962-2016 show that the presence of games in these cities increased local influenza mortality by between 4% and 24%, depending on the sport, relative to cities with no professional sports teams and relative to mortality in those cities before a new team arrived. Influenza mortality fell in cities with teams in some years when work stoppages occurred in sports leagues. Sports league reopening policies should take into account the role played by sporting events in increasing local seasonal flu mortality.

We thank participants in the ROSES seminar hosted by the University of Reading, UK, for useful comments and suggestions.

A Diagrammatic Depiction of the Rottenberg Invariance Literature

- Dennis Coates, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and HSE University , coates@umbc.edu

Motivation

The sports economics literature traces much of its active research agenda to issues raised by Simon Rottenberg in his seminal article “The Baseball Players’ Labor Market”. One issue, perhaps the single most examined issue, is the extent to which the equilibrium outcome in the sports labor market is invariant to alternative institutions in that market. In what has come to be known as the Invariance Proposition, Rottenberg states: „It seems, indeed, to be true that a market in which freedom is limited by a reserve rule such as that which now governs the baseball labor market distributes players about as a free market would (Rottenberg, 1956, p. 255).“

The Invariance Proposition implies that the sporting competition under the reserve rule distributes wins about as a free market in player labor would. Natural developments of the literature include the assessment of alternative league policies, like salary caps and revenue sharing, for what they implied for the distribution of wins among the teams in the league, and the extent to which the Invariance Proposition would hold in the win-maximizing setting of European football. The purpose of this paper is to present a fairly simple diagrammatic model that combines these insights.

Theoretical description

The model assumes a two-team league and clubs that are profit-maximizers. Profit functions exist that relate profits to winning percentage, deriving from the difference between the revenue and cost functions. These profit functions have the regular inverted U-shape implied by a revenue function that is concave in winning percentage and a cost function that is convex in winning percentage. In addition to the profit functions of the two clubs is a constraint that the winning percentages of the two clubs add to 100. Putting these functions in their own quadrant of a four quadrant diagram, one can go from every competitive outcome in winning percentage tot he profit of each club. Those profits identify a point on a curve identified as the profit possibility frontier. The profit possibility curve identifies every combination of profits for the two clubs that can be generated from a logically consistent league outcome, that is, one that satisfies the adding up constraint on winning percentages, given the revenues and costs faced by each club.

Main results

The Invariance Proposition is reflected in the profit possibility function for a simple reason: the cost function reflects all opportunity costs of production, including those associated with keeping or selling a player contract under the reserve clause. Under a free market in players, the player gets the surplus his/her performance generates, but the opportunity cost to the clubs is no different than under the reserve clause. Consequently, under either labor market regime, the profit possibility frontier is in exactly the same position. The winning percentage combinations and their associated profits are the same whether players labor under the reserve clause or free agency, so the competitive balance is invariant tot he labor market regime.

League policies like revenue sharing and salary caps change one or both of the position and the shape of the profit possibility frontier. Doing so means it is unlikely to produce the same winning percentage pairs with and without such policies.

Racial Discrimination and the Home Advantage Effect – New evidence from Tennis

- Carsten Creutzburg, University of Hamburg, steffen.mueller@uni-hamburg.de

- Wolfgang Maennig, University of Hamburg

- Steffen Q. Mueller, University of Hamburg

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that fan support contributes to the home advantage effect in various sports (e.g., Jones 2013; Downward, Dawson and Dejonghe 2009; Koyama and Reade 2009). (Previous research typically distinguishes between four factors contributing to the home advantage effect: Crowd factors, familiarity with local conditions, travel factors and rule factors. A large share of research suggests that crowd factors are a major driving force of the home advantage effect, see, e.g., Jamieson (2010) and Anders and Rotthoff (2014).) Similarly, it typically assumed than fans prefer players to be of similar race as their own, and previous research finds that fan discrimination can impact can impact stadium attendance (e.g., Tainsky and Winfree 2010), TV ratings (e.g., Konjer, Meier and Wedeking 2017), social media consumption (e.g., Watanabe et al. 2017), collectible purchases (e.g., Nardinelli and Simon 1990), and All-Star voting (e.g., Hanssen and Andersen 2017). The literature on the home advantage effect in sports is extensive (corresponding literature surveys are provided by, e.g., Schreyer and Ansari (2021), Jamieson (2010), and Courneya (1992)); however, while existing studies typically incorporate previous potential differences in the home advantage effect across locations, existing research does not account for player race and ethnicity (e.g., Koyama and Reade 2009; Koning 2011; Filipcic et al. 2013; Ovaska and Sumell 2014; Chun and Park 2021). In contrast, this is the first study to assess the extent to which the home advantage effect depends on players’ racial and ethnic affiliations.

In this study, we investigate the potential impact of fan discrimination on the home advantage effect by predicting individual game outcomes using men’s professional tennis data from 2001 to 2017. (The original data set covers 46,930 individual matches played over the course of the 2001 to 2017 season. We discard 1,771 matches that have not been finished regularly due to retirement, disqualification, or walkover. In addition, we drop 914 matches with missing odds-data, resulting in a final sample size of 44,930 individual games. The data include games from the tournaments: Grand Slams (18%), ATP Finals (1%), ATP Tour Masters 1000 (21%), ATP Tour 500 (14%), and ATP Tour 250 (46%). The largest share of games is played on hard court (54%) and the predominant condition is outdoor (82%). In 33,169 (74%) of the matches, none of the two players has a potential home advantage. In 10,410 (23%) matches, one player has a potential home advantage, and there are 1,351 (1%) matches with two home players. The data used in this study are collected from atptour.com (game and player data) and tennis-data.co.uk (betting odds).) To this end, we analyze two different outcome variables. In addition to using the binary game outcome (did the player with a home advantage win), as an innovation of our study, we use winning probability derived from betting odds as numeric outcome variable.

A major obstacle in the empirical analysis of discrimination in sports markets is the scarcity of available information on player race and ethnicity (Foley and Smith 2007; Hamrick and Rasp 2015; Kahn 1992). As a result, it is common practice to determine racial and ethnic profiles by manually inspecting player pictures and/or names and birthplaces (Hanssen and Andersen 2007; Tainsky, Mills and Winfree 2015). Following recent advances in discrimination research, similar to Maennig and Mueller (2021) we combine automated data acquisition and racial identification techniques to reduce data collection costs and mitigate human bias in race classification. We first use web scraping techniques to collect pictures on 1,174 individual players; then, we use a deep-learning based facial recognition API to identify groups of players with similar racial appearance. However, unlike previous research, we innovate by using a k-means clustering approach based on the API race category predictions to identify different clusters of players with similar racial and ethnic profiles (We use the “Kairos” face recognition API that gives percentage values for four race groups (Asian, black, Hispanic, white, and other.); the resulting procedure results in five racial categories: African (N=29), Asian (78), Caucasian (N=627), Indian (N=16), and Southern (N=424).

Summarizing our preliminary findings based on linear and logistic regression using game outcome and winning probability as dependent variables, this study provides evidence for the existence of a home advantage effect in tennis that significantly varies by player race and tournament location. As an example, compared to Caucasian players, we find Southern players to have a significantly larger home advantage effect, whereas Asian players have a significantly lower home advantage effect than Caucasian players. In addition to the home player’s race, we find the opposing player’s race to be a relevant determinant of the home advantage effect. For instance, home advantage effect is decreased for Indian players when facing a black opponent; similarly, we find a significantly lower home advantage effect for Southern players competing against Asian players.

Judged events at the Olympics: do the determinants of success differ?

- Gergely Csurilla, Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Budapest, Hungary; Sport Economics and Decision Making Research Centre, Hungarian University of Sports Science, Budapest, Hungary

- Imre Fertő, Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Budapest, Hungary; Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Gödöllő, Hungary

Introduction

Countries hosting the Olympic Games typically allocate extra resources to their elite sports as soon as they are selected. On the one hand, to support their athletes to take advantage of the home field. On the other hand, they are trying to justify the organisation of the event and the costs involved by the increased number of medals.

The existence host effect has been identified in all studies investigating the determinants of countries’ success at the Olympic Games. Forrest et al. (2017) were the first who estimated the previously used indicators separately by sport. The GDP per capita and the population size affect the results significantly in all events in the sample. However, not all the sports showed a significant effect for home advantage. The sports where a significant effect was found are typically those where subjectively judging affects the results. Balmer et al. (2001) have also achieved similar results for the Winter Olympics. In sports where the outcome is determined by the subjective judgements of the judges, the host effect has a greater impact. In a later study, this finding was also confirmed for the Summer Olympic Games (Balmer et al., 2003).

The host effect and the other determinants of success also show differences by gender at the Olympic Games. Gender differences between the Summer and Winter Olympics exist, with the host effect for women being largely insignificant at the Winter Olympic Games (Noland & Stahler, 2017; Singleton et al., 2021). Rewilak (2021) shows a similar positive home advantage for both genders.

Evidence for the judging bias in subjectively judged sporting competitions has been identified in individuals (Emerson et al., 2009) and also in country-level (Waguespack & Salomon, 2015). However, the difference in the determinants of success between judged and non-judged events has not been studied before. In this paper, we address this issue from different aspects.

Several issues arise from previous studies of the Olympic Games’ judged competitions. First, most studies had limited samples or observations. Second, the results are almost invariably based only on the total number of medals, with no gender differences examined. Finally, recent studies highlight the importance of newer empirical methods that could better handle the problem of zero observations in the Olympic data compared to the previously used estimators (Csurilla et al., 2021; Duráczky & Bozsonyi, 2020; Rewilak, 2021). In our study, we provide answers to all these issues.

Data and methodology

We employed data about medal counts of the Summer Olympic Games between 1996-202. Due to regime changes and boycotts in the 1990s, the results of earlier Olympics cannot be used for a longitudinal analysis (Forrest et al., 2017). Instead of aggregate data, we used the sport-level medal count to obtain more detailed information about countries’ Olympic performance (Singleton et al., 2021). We used data from the database of the World Bank for the socioeconomic indicators.

We used the Olympic medal counts of countries for sports (total, men, and women) as the outcome variable. The logarithmic forms of GDP per capita and population, host dummy, communist dummy, and a super dummy for controlling the outstanding performance of the three superpower countries (the USA, China, Russia) were applied as explanatory variables. As having a sports-level panel dataset, we included two-way fixed effects in the models to control heterogeneity over time and across sports (Singleton et al., 2021).

To measure the determinants in judged and non-judged events, we split our sample into three parts; judged, non-judged, and team sports. As the number of observations in team sports is low, these were excluded from the analysis. The estimations were performed for judged and non-judged samples and by gender separately. To handle the issue of mass zero observations in the outcome variable, a zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression was applied as an estimator (Hilbe, 2014).

Results

We first estimate the models on the full sample. Only one coefficient is not significant in one case. The super dummy shows no effect on the medals won by men. In addition, all other variables have a positive effect on the Olympic medals.

When we split the data by the type of event, the coefficients of host effect, superpower countries, communist dummy, and the GDP per capita in the zeroinflate model change remarkably. The super dummy loses its significance in judged and men events. The technological advantage of the three countries is likely to be more pronounced in non-judged events. In all cases, the host effect is slightly higher in the judged events. This suggests some judging bias; however, the differences are not statistically significant. Coefficients of the communist dummy are significantly higher in the judged events also for men, women, and total medals. Former communist countries might focus more on judged sports.

One of our most interesting findings is that the GDP per capita positively affect the probability of not winning a medal in judged events in the case of total and men’s medals. This odd result may be explained by the hectic nature of the judges’ actions. Or that many of the wealthier countries do not focus on these sports due to their hectic nature.

The introduction of a minimum wage in Germany and the effects on physical activity

- Sören Dallmeyer, German Sport University, s.dallmeyer@dshs-koeln.de

- Christoph Breuer, German Sport University

Introduction

On the 1st of January in 2015, the German government introduced the first statutory uniform minimum wage of 8.50€ per hour in the history of the country. Over the following years, the minimum wage was gradually raised to 8.84€ in 2017 and 9.19€ in 2019. With around 4 million people being affected by the regulation (Lesch & Schröder, 2016), the decision by the policy-makers to intervene was in particular driven by the aim to prevent poverty and to reduce income inequality among the German population (Kalina & Weinkopf, 2014).

In the past, both economic indicators have been proven to affect numerous dimensions of an individual’s health in Germany (Aue et al., 2016; Picket et al., 2016). Accordingly, previous research has also focused on the relationship between an introduction or an increase of a minimum wage and numerous health outcomes. In fact, Leight et al. (2018) found in their recently published review that the number of studies investigating this relationship has increased rapidly over the last couple of years. For example, research has found a positive effect of an increase or the new introduction of a minimum wage on self-reported health (Lenhart, 2017), mental health (Reeves et al., 2017), obesity (Andreyava & Ukert, 2018), and birth weight (Strully et al., 2010). The evidence on health behavior, in particular physical activity, however, is rather scarce, in particular when it comes to participation in physical activity. Hence, this study investigates if the introduction of the minimum wage in Germany has affected the physical activity behavior of the German population.

Conceptual framework and literature review

From a theoretical perspective, Horn et al. (2017) explain the positive health outcomes of a minimum wage by using a simplified version of the Grossman model (1972). This economic model on the demand for health and healthcare assumes that every individual has a durable capital stock of health which depreciates over time at a certain rate and by investing in either market goods or non-market goods the individuals can restore their health. Horn et al. (2017) noted that minimum wages are unlikely to affect neither the capital stock of health nor the depreciation rate but instead can have an influence on the individual’s investment in their health by affecting the income level and time costs. With a higher income, people can consume more market goods to improve their health.

However, they can also use the higher earnings to consume non-healthy goods such as alcohol or smoking. For time costs the potential effect is twofold as well. With a higher income the opportunity costs of time increase which can have a diminishing effect on the consumption of non-market goods. On the other hand with the potential negative effects on employment in mind, it is possible that people will experience lower working hours which can lead to more time for the consumption of non-market goods.

The existing literature has investigated the effect of minimum wages in particular on smoking and alcohol consumption. While Leigh et al. (2018) were able to find a significant decrease in smoking behavior in their review of existing studies, the findings regarding alcohol consumption were rather inconclusive.

Surprisingly, physical activity has not received much academic attention, yet. Only the study from Horn et al. (2017) has looked at this relationship as part of an auxiliary analysis. The researcher used a very broad measure of physical activity (exercise in the last 30 days, yes/no) and found evidence that women are more likely to report physical activity following a minimum wage increase. The relationship to physical inactivity is interesting because of numerous reasons. First of all, the wide range of health problems associated with physical inactivity, well-documented by existing research, makes it one of the major public health challenges. Accordingly, governments worldwide are looking for policy interventions to promote physical activity among the population. Second, the two outcomes of minimum wages, higher income levels, and time costs have been identified as important determinants of participation in physical activity in the past. Humphreys & Ruseski (2012) have investigated both and found that a higher income has a significant positive effect on participation in physical activity. However, regarding the increase in times costs, the authors found that the higher levels of income had a significant negative relationship with duration of participation, likely due to the higher opportunity costs. In a follow-up study, Humphreys & Ruseski (2015) revealed that this two-fold effect is likely depending on the kind of physical activity. For example, a higher income is positively associated with participation in swimming or golfing, whereas a negative effect was found for walking or exercising at home. Due to those findings, the relationship between minimum wages and physical activity is likely to differ between the decision to participate and the duration of participation.

Our study aims to shed further light on this relationship by using more detailed measures of physical activity. The data stems from the German Socio-Economic Panel which includes detailed information on the working conditions of the individual. Additionally, two different measures of physical activity are available: One measuring the frequency on an ordinal scale from never to more than once a week and one measuring the numbers of hours participating in physical activity per working day.

Methods

The analysis of the relationship between the introduction of a minimum wage and physical activity is based on the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) (GSOEP, 2021). The GSOEP is a German household panel survey conducted annually by the German Institute of Economic Research since 1984. In previous research, the survey data has already been utilized to examine determinants (Breuer & Wicker, 2008) and outcomes of physical activity (Lechner, 2009). With regard to the introduction of a minimum wage, the GSOEP has been used to investigate numerous employment effects (Caliendo et al. 2018) and Gülal & Ayaita (2018) looked at the effect on various well-being outcomes.

With the minimum wage being introduced in 2015 and adjusted in 2017 and 2019, the present study uses data from the period 2013-2019.

Given the focus of the analysis is on the minimum wage, only individuals of the official working age in Germany (16-65 years) are included. The final sample size of the study consists of n=18,657 with n=4,841 respondents before the introduction of the minimum wage in 2013 and n=13,816 after the introduction in 2015, 2017, 2019

The study applies a difference-in-difference (DiD) approach to estimate the causal effect of the introduction of minimum wage in 2015 on physical activity in Germany. The DiD captures how the participation in physical activity in the treatment group changes in comparison to the control group. Thereby, the treatment group consists of individuals who receive an hourly wage below 8.50€ before the new minimum wage was introduced in 2015. The control group captures individuals who receive an hourly wage higher than 8.50€ but only up to 12.75€ (50% more).

Preliminary findings

The results show a significant positive effect on the number of individuals being active once a week and on the duration of physical activity when comparing the treatment to the control group. A differentiation by gender revealed that the positive effect of a minimum wage for participation frequency and duration can only be observed for females. Further, the analysis does not show any additional effects of the different raises of the minimum wage level in 2017 and 2019.

The well-being, health, and social value of grassroots football in Europe: Gender-based insights

- Paul Downward, Loughborough University, p.downward@lboro.ac.uk

- Pamela Wicker, Bielefeld University

- Tim F. Thormann, Bielefeld University

Introduction and motivation

In recent years, public policy has promoted sport participation across Europe because of benefits to health (Downward et al., 2021), social capital (Davies et al., 2019), and well-being (Downward & Dawson, 2016; Huang & Humphreys, 2012; Ruseski et al., 2014; Wicker, 2020). Whilst it has long been argued that greater sport (and physical activity generally) can help to reduce health care costs (Dallmeyer et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2017), increasingly social return on investment (SROI) analyses have emerged. These investigate the case for increased investment in sport aimed at drawing down the benefits associated with sports beyond the economic impact arising from tangible consumption expenditures (Davies et al., 2019). A key feature of SROI analyses is the need to monetize the returns from such investments that, due to their intangible nature, represent non-use values. The compensating variation or well-being valuation approach is one example of how this can be achieved (Orlowski & Wicker, 2019; Thormann et al., 2022). This study makes use of this approach to answer two research questions connected with football in Europe:

- How does participation in different types of football affect male and female social capital, well-being, and health?

- What monetary values can be assigned to these effects?

The focus on football is for three reasons. First, it is typically the largest participation team sport (Lechner & Downward, 2017). Second, and shared with some other sports, football participation can take place in a variety of formal and informal contexts (Jeanes, 2019). Finally, it is a sport that is rapidly developing for females and challenging existing patterns of sport participation (Pfister, 2015). Addressing the research questions in this context can inform future investment by governing bodies.

Theoretical foundations

The compensating variation approach that is drawn upon has its roots in microeconomic theory (Fujiwara & Campbell, 2011; Orlowski & Wicker, 2019). This approach postulates that a set of factors influence well-being, social capital, and health, and these include the forms of football that they participate in. Identifying the contribution of both the football participation and the individual’s income to the outcomes of interest allows for the monetization of the contribution of football to that outcome. A large literature has identified the contributions of sport to the outcomes investigated (e.g., Kumar et al., 2019). However, less have identified the monetary values associated with the outcomes associated with sport – with a few exceptions (Downward & Rasciute, 2011; Downward & Dawson, 2016; Orlowski & Wicker, 2018; Thormann et al., 2022).

Empirical approach

The analysis draws on survey data collected from February 22nd to March 8th, 2021 from respondents recruited from the online consumer panels of Toluna. Sub-samples of 1,000 individuals were gathered for the UK, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, Russia, and Sweden, and 500 individuals from Bosnia, resulting in a full sample of n=7500 respondents. The aim was to capture different geographic segments of the football market in Europe. The country-specific sub- samples were nationally representative in terms of age, gender, and income. Country-specific sub-samples included at least 400 footballers, except for Bosnia, to provide sufficient observations to draw a contrast between participation or not given the relatively low levels of participation in team sports in general and football in particular.

A questionnaire was developed to measure the outcomes of health, well-being, and social capital drawing on questions for previous large-scale surveys such as the Taking Part Survey in the UK (Downward & Dawson, 2016) and the German Socio-Economic Panel (Orlowski & Wicker, 2018). Specifically, subjective well-being was captured with a question assessing individuals’ general happiness on a scale from 0 to 10. Individuals’ health was measured with a subjective statement about the perceived general health status (on a five-point scale). Social capital was captured with a question asking for the perception of how much people can be trusted in general on a scale from 0 to 10.

The independent variables of interest are the forms of respondents’ football participation, gender, and a number of confounding factors (e.g., age, number of children, educational level, being a couple, watching football, income). The different forms of football included: formal 11-a-side football, small-sided football (at a facility), futsal, informal football (in a public space), and walking football. Importantly, given the timing of the sampling period, respondents were asked to answer the questions based on the season before the Covid-19 pandemic arrived.