This page gathers the extended abstracts from Topic 3 of the Compass Conference: Transferable Skills for Research & Innovation, 2023, October 4 – 5, Helsinki, Finland.

Contribution to Human Maintenance as Tool For Sustainable Health

Onofrejova, D.

Corresponding author – presenter

daniela.onofrejova@tuke.sk; Technical University of Kosice, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Institute of Special Engineering Processologies, Department of Safety And Production Quality, Slovakia

Porubcanova, D., Balazikova, M., Pacaiova, H.

Technical University of Kosice, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Institute of Special Engineering Processologies, Department of Safety And Production Quality, Slovakia

Key words: exoskeletons, sustainable health concept, physical load, mental load, musculoskeletal disorders

Background of the study/literature review

Human Maintenance as a tool for sustainable health is an emerging field that explores innovative approaches to enhance human well-being and prevent health issues [1]. This abstract examines the role of exoskeletons, the concept of sustainable health, and the impact of physical and mental load on musculoskeletal disorders. By integrating exoskeleton technology, health prevention strategies, and a sustainable health concept, it is possible to mitigate the negative consequences of physical and mental stressors, ultimately leading to improved overall health and well-being.

In the pursuit of sustainable health, preventive and predictive maintenance strategies have proven to be invaluable tools [2]. Traditionally applied to mechanical systems and equipment, these maintenance approaches are now finding application in the realm of human maintenance. By proactively addressing health issues before they arise, these strategies can revolutionize the way we approach individual well-being and contribute to sustainable health.

Planned and preventive maintenance involves taking measures to prevent the occurrence of health problems [3]. This approach emphasizes regular check-ups, health screenings, and lifestyle interventions to detect early signs of illness and implement necessary preventive measures. By adopting preventive maintenance practices, individuals can identify potential health risks, modify behaviours, and make informed decisions to promote long-term well-being. Preventive maintenance can help mitigate the development of chronic diseases, manage risk factors, and reduce healthcare costs associated with reactive treatments.

Predictive maintenance, on the other hand, takes advantage of advanced technologies and data analysis to forecast potential health issues. By utilizing wearable devices, biosensors, and artificial intelligence algorithms, predictive maintenance can monitor physiological parameters, detect abnormalities, and provide personalized health recommendations. This proactive approach enables individuals to take timely actions, seek medical attention when necessary, and make necessary lifestyle modifications to prevent the progression of health conditions.

Musculoskeletal disorders are a common health concern, affecting millions of people worldwide. The integration of exoskeleton technology, health prevention strategies, and sustainable health concepts offers a multifaceted approach to address these disorders.

Exoskeletons can provide real-time feedback on body mechanics and posture, promoting ergonomic practices and reducing the risk of musculoskeletal injuries [4, 5]. Additionally, by minimizing physical and psychological loads, exoskeletons can prevent the progression of existing musculoskeletal disorders and aid in the rehabilitation process.

Aim of the study including original & novelty

Exoskeletons have gained considerable attention in recent years as a promising tool to assist individuals in various physical tasks. These wearable devices, passive or active (robotic), provide external support to the body, reducing physical load and preventing injuries.

By augmenting human capabilities, exoskeletons not only enhance performance but also reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders caused by repetitive motions, prolonged standing and excessive strain. They distribute the physical load evenly across the body, minimizing the impact on specific joints or muscles, thereby improving long-term health outcomes [4].

Health prevention is a crucial aspect of sustainable health. By proactively addressing potential health risks and promoting healthy behaviours, individuals can reduce the likelihood of developing chronic conditions [5]. Integrating exoskeleton technology into health prevention strategies offers unique opportunities for sustainable health maintenance.

Exoskeletons can be employed in various occupational settings, such as heavy lifting tasks in industries or repetitive movements in healthcare professions. By incorporating exoskeletons into these work environments, the physical load on workers can be significantly reduced, leading to decreased injury rates and improved overall health.

Moreover, sustainable health encompasses not only physical well-being but also psychological well-being [6]. Psychological load, such as stress and mental strain, can have a profound impact on an individual’s health. High levels of stress are associated with various negative health outcomes, including musculoskeletal disorders [7]. Exoskeleton technology can play a significant role in mitigating the psychological load by reducing the physical demands of tasks, allowing individuals to focus on their cognitive and emotional well-being [4]. By alleviating physical strain, exoskeletons contribute to a healthier work environment and help prevent the development of stress-related disorders.

Human maintenance as a tool for sustainable health is a vital area of research and development. Instead of waiting for symptoms to manifest or relying solely on reactive treatments, individuals can take control of their health by actively engaging in preventive measures. This approach promotes sustainable health by emphasizing early intervention, individual responsibility, and proactive decision-making. The implementation of preventive and predictive maintenance can lead to significant cost savings and resource optimization within healthcare systems. By focusing on prevention, the burden on healthcare facilities can be reduced, and resources can be allocated more efficiently. This contributes to sustainable healthcare practices by ensuring that limited resources are utilized for those in need and promoting equitable access to healthcare services.

Methodology (the methods used in your research including data collection and data analysis)

The methodology can vary depending on the specific context and objectives. However, here are some key methodologies that can be applied:

- Data Collection and Analysis:

Collecting and analyzing relevant data is crucial for understanding the current state of health and identifying areas that require intervention. This can involve gathering health records, conducting surveys, utilizing wearable devices for physiological monitoring, and employing data analytics techniques to extract valuable insights.

- Risk Assessment:

Conducting comprehensive risk assessments allows for the identification of potential health risks and the development of preventive strategies. This can involve evaluating individual health profiles, assessing occupational hazards, considering lifestyle factors, and analyzing genetic predispositions. Risk assessment methodologies such as hazard identification, exposure assessment, and risk characterization can be applied.

- Health Promotion and Education:

Implementing health promotion and education programs is essential for fostering sustainable health practices. This involves disseminating knowledge about healthy lifestyles, providing resources for behaviour change, and promoting the adoption of preventive measures. Methods such as workshops, seminars, online platforms, and targeted campaigns can be employed to raise awareness and educate individuals.

- Proactive Interventions:

Implementing proactive interventions aims to prevent health issues before they arise or manage them in their early stages. This can involve regular health screenings, vaccinations, lifestyle interventions (such as exercise programs and dietary modifications), and the use of predictive technologies to monitor health indicators and provide personalized recommendations.

- Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation:

Establishing a system for continuous monitoring and evaluation allows for the assessment of the effectiveness of interventions and the identification of areas for improvement. This involves tracking health outcomes, monitoring the utilization of preventive services, and soliciting feedback from individuals. Evaluating the impact of interventions and adjusting strategies accordingly ensures the sustainability and effectiveness of the approach.

It is important to note that the specific methodology employed will depend on factors such as the target population, available resources, technological advancements, and the desired outcomes.

Result/findings and argumentation

The sustainable health concept emphasizes the interdependence of human health and the environment. It recognizes the importance of maintaining a healthy population to ensure the sustainable development of societies. Exoskeletons can provide support and assistive forces to mitigate the risk of developing MSDs. By redistributing the forces exerted on the

body, exoskeletons help individuals maintain a proper posture and mitigate the risk of over exertion, thus promoting long-term musculoskeletal health. By reducing the physical load on the body, exoskeletons promote musculoskeletal health and prevent chronic conditions that can lead to disability. Exoskeletons, with their potential to reduce work-related injuries and improve productivity, align with the principles of sustainable health. By preserving human resources, preventing disability, and enhancing well-being, exoskeletons contribute to a sustainable and resilient society. Smart exoskeletons with embedded sensors monitoring vital functions will be used.

In addition to addressing physical load, exoskeletons also play a significant role in mitigating psychological load. The psychological aspects of work, including stress, anxiety, and mental fatigue, can have detrimental effects on individual well-being. Exoskeletons can assist in reducing the mental and emotional strain associated with physically demanding tasks by providing a sense of physical support and enhancing the user’s confidence. This, in turn, contributes to the overall psychological well-being of individuals, leading to sustainable health outcomes.

By implementing health prevention measures and considering the environmental impact of healthcare practices, societies can foster sustainable health and ensure the long-term well-being of individuals and communities. Continued research, innovation, and collaboration among various stakeholders are essential to realizing the full potential of exoskeletons and establishing sustainable health practices in the future.

In the quest for sustainable health, it is imperative to explore innovative approaches that not only address the current health challenges but also provide long-term solutions.

Conclusion, managerial implications and limitations

Health prevention plays a crucial role in sustainable health. It encompasses proactive measures aimed at reducing the incidence of diseases, injuries, and other health-related issues. By implementing preventive strategies such as regular exercise, ergonomic training, and health screenings, individuals can minimize the risk factors associated with physical and psychological loads. Exoskeletons can be integrated into health prevention programs to promote safe and sustainable working environments.

The potential impact of exoskeletons on sustainable health is vast. In industries such as manufacturing, construction, and healthcare, where physical demands are high, the adoption of exoskeleton technology can lead to a significant reduction in workplace injuries and associated healthcare costs. By promoting healthier work practices, exoskeletons also enhance productivity and overall job satisfaction, contributing to sustainable economic growth.

To realize the full potential of exoskeletons as a tool for sustainable health, several factors must be considered. These include accessibility, affordability, and user-friendliness of exoskeleton technologies. Additionally, extensive research and development efforts are needed to refine and customize exoskeletons for specific applications, considering individual variations in body morphology, task requirements, and user preferences.

The application of preventive and predictive maintenance in human maintenance has to transform the way we approach individual well-being and sustainable health. By shifting the focus from reactive treatments to proactive measures, individuals can take charge of their health and prevent the onset or progression of health issues. Moreover, these strategies can lead to cost savings and resource optimization within healthcare systems, fostering sustainability in the provision of healthcare services in achieving sustainable health for all.

References

- Pagán-Castaño, E., Maseda-Moreno, A., Santos-Rojo, C. (2020) Wellbeing in work environments. Journal of Business Research, Volume 115, 469-474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.007.

- Sheikhalishahi, M., Azadeh, A., Pintelon, L., Chemweno, P. (2017) Human Factors Effects and Analysis in Maintenance: A Power Plant Case Study. Quality And Reliability EngineeringInternational. 33(4), 895-903, https://doi.org/10.1002/qre.2065

- Illyani, B. E., Razak, A., Hamimi, I., Samat, A., Hasnida, Shahrul, K. (2017). Preventive Maintenance (PM) planning: a review. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering. 23. 10.1108/JQME-04-2016-0014.

- Pacaiova, H., Onofrejova, D. (2022) Assessment of the Effectiveness and Safety of Exoskeletons in Industrial Workplaces. In: Safety Management and Human Factors : Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics. New York (USA) : AHFE International s. 117-124 [online]. https://openaccess.cms-conferences.org/publications/book/978-1-4951-2091-6/article/978-1-4951-2091-6…

- Onofrejova, D., Balazikova, M., Glatz, J., Kotianova, Z., Vaskovicova, K. (2022) Ergonomic Assessment of Physical Load in Slovak Industry Using Wearable Technologies. Applied Sciences. 12(7): 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073607

- Litchfield, Paul, Cary Cooper, Christine Hancock, and Patrick Watt. (2016) Work and Wellbeing in the 21st Century. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13(11): 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111065

- Warr, P., & Nielsen, K. (2018). Wellbeing and work performance. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers. DOI:nobascholar.com

Creating discourses, integrating ideas:

The Antonine Chancery as the first large-scale European communication network

Rodríguez Pérez, R.

rrodriguez5@us.es, Universidad de Sevilla, Spain

Keywords: communication, idea transfer, history, Ancient Rome, state bureaucracy.

Background of the study

In an increasingly connected world, the way discourses and ideas have circulated Europe throughout the centuries is more topical than ever. Studies on medieval and early modern communication networks have a long scholarly tradition; with direct ties to the world of religion and the concept of Christendom, the Apostolic Chancery has been the subject of many analyses over the last decades (Meyer, 2016) (Märtl, 2021). The same happened with the emergence of modern states and the establishment of their own networks on a smaller scale (albeit sometimes more challenging to implement, especially after the birth of colonialism) (Erikson, 2014), which eventually fused leading up to a globalized world. Classicists, however, have paid little attention to these types of developments, despite finding in the Roman Empire the indisputable precursor of later models and institutions.

Aim of the study

The main hypothesis of this study is that the Roman emperors and their chanceries, from the beginning of the 2nd century until the breakdown of political stability in the first third of the 3rd century, were a major force for the integration of the various peoples who had been included within the empire. Because of their provincial roots and seeking to make their own power firmer and more stable, the emperors wanted to make themselves present in the territory of the Empire. They were building a kind of consensus with the local and regional oligarchies that could be extended to the rest of the social classes and that would guarantee the stability of the Empire in a century when military problems on the frontiers were gradually worsening. Over time and with the continuous action of integration, this consensus built up a new imperial community identified by its political character, a legacy of the civic origin of Rome, but also religious, as a community of gods and men. This process finds in the Constitutio Antoniniana the final milestone in the process of integration, for with it the emperor proclaims, creates in a way, the community of gods and of rights and duties that the Empire had become.

Well, we believe that the study of the abundant texts written by the emperors themselves (or by secretaries who spoke for them) will provide us with an insight into the discourse that the emperors were weaving about themselves, their subjects, the relationship that existed between them and the location of all of them in a world governed by the gods. Far from the image of a passive emperor, waiting for problems to be posed to him from the cities of the provinces in order to solve them in a process of request and response that was recreated from the beginning with each action, as Millar (1977) had defined it, the emperors of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, through their letters, rescripts and speeches, appear as a driving force of integration. They appear as active agents, willing to develop their own projects of a local or general nature, which seem to have been born out of a uniquely deep and sometimes independent knowledge of the needs of the regions and cities of their empire. As put forward by Edmondson (2015) and Cortés (2017), this enabled them to become promoters of measures to transform the political and economic landscape, which would undoubtedly have been born of their own ideas about the meaning of prosperity and happiness for their subjects, as well as the unity and integration of the Empire.

Thus, the aim of our project is to portray the Imperial Chancery of Antonine times as what it was: theinstrument of the first large-scale European communication network, one that allowed and fostered the rise of a common culture (Graeco-Roman; Mediterranean; European; Western). There are two main objectives:

- The analysis of the Antonine Chancery in its most practical dimension: the sending of documents, their transport, the storage and the complex bureaucratic apparatus behind the whole network, divided by officia run by secretaries of equestrian rank (e.g., ab epistulis, a libellis, a rationibus).

- The study of the documents’ content and their contribution to the creation of the aforementioned common culture and political identity.

Methodology

As with any research of a historical nature, the methodological focus is on the careful study of the sources. Only by establishing a full corpus of the preserved documents from the Antonine Chancery can we delve into the mechanisms and ideas expressed in them with a holistic approach.

Data collection, thus, consists on the compilation of said documentation, which was originally writtenin perishable material but is now preserved through the copies that some of the recipients engraved on hard surfaces (namely bronze, limestone and marble). These copies or antigrapha are mainly attested on the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean, as it was the Greek poleis that had themeans and tradition of conserving such imperial resolutions. Some of them appear on general corpora (e.g., Inscriptiones Graecae, Corpus Instriptionum Graecarum, Tituli Asiae Minoris), whereas others remain unedited to this day. We have already conducted a thorough, in situ study of the inscriptions in Greece and modern Bulgaria, making tangible progress in the creation of a unitary and updated catalogue on the Roman Imperial Chancery. Subsequently, the resulting texts have been translated from their original language and analysed on the basis of what light they can shed on each of the following aspects:

- The technical details and inner workings of the chancery.

- The concepts of justice and humanity and their usefulness in governmental action.

- The image the emperor conveys of himself in his writings: accessibility, mutual respect, appreciation of the richness of the empire’s traditions, temperance, etc.

- The emperor as judge, provider of benefits, restorer of rights, guarantor of traditions.

- The emperor as the ultimate source of law and justice; the emperor as a living law through his own words.

- The representation of subjects in imperial writings: merits adduced to obtain benefits, acceptance of imperial decisions or reluctance to accept them.

- The religious components in the political communications of the emperors: the gods in imperial letters and speeches. The concordia deorum, the acceptance and protection of the local gods in the common framework of the Empire, the emperor before the gods, the emperor among the gods, the emperor as a delegate of the gods.

- The empire as a cultural community: the organisation of an ecumenical framework for the holding of the Greek contests as an instrument for the constitution of the new community. The emperors as the driving force of the process and the guarantors of its preservation and development.

It is not a matter of making analyses of administrative structures that have already been done and are useful, but of analysing how the emperor himself is presented as directing what we have called the “integrated management” of the Empire. This means that the emperors, mainly through their letters, give news of how they were able to unite the different parts of Roman power in unitary management processes. Emperor, governors of provinces, military commanders, cities, temples, associations of various kinds, imperial procurators, imperial agents of various ranks, etc. all appear united in management processes that integrate them into a single political-administrative reality. This representation, this discourse, creates not only the image but also the reality, as far as possible, of an efficient empire, capable of solving its problems. This image of institutional solidity was an essential part of the Empire’s discourse that was transmitted through its extensive communication network.

From the emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD), considered the promoter of the great reforms involving the Empire’s bureaucratic apparatus (and therefore founder of the Antonine Chancery), more than 60letters have survived through antigrapha, which is more those we can attest for all the previous emperors combined. His successor Antoninus Pius perfected the system and sports similar numbers, with a total of 58 attestations. Our study, thus, gravitates around the work of these two sovereigns, whose reigns constitute one of the most stable, peaceful eras of all Roman history.

Findings and conclusion

As a work in progress, our complete set of aims remains to be fulfilled, though in the current state ofour investigation it can be safely stated that the Antonine Chancery set up a bidirectional channel (from emperor to provinces, and from provinces to emperor) of idea transfer that was of unprecedented scale in the European oikoumene.

Aside from what this means for administrative history and communication studies, we believe ourdocumentation can also be of great use to legal scholars, as a big percentage of the petitions put forward by the citizens to the Roman central power via Imperial Chancery (libelli) had a legal nature. As already mentioned, the emperor’s response was not only an act of communication, but an act of lawmaking as well, his resolutions being considered constitutiones that established jurisprudence.

In our opinion, awareness about the existence of such a network way before the catalyst of Christianity or modern communications is essential for the understanding of the forging of European identity, as well as the relations between the Greek East and the Latin West (a division that is very much alive today, only with the names of Eastern and Western Europe).

References

Ando, C. (2015). Petition and Response, order and obey: contemporary models of Roman government. In H. Baker et al., Governing Ancient Empires. Vienna: WUPress.

Cortés, J.M. (2017). Governing by Dispatching Letters: The Hadrianic Chancellery. In C. Rosillo-López, Political Communication in the Roman World. Leiden: Brill.

Edmondson, J. (2015). The Roman emperor and the local communities of the Roman Empire.

In J.L. Ferray & J. Scheid, Il princeps romano: autocrate o magistrato? Fattori giuridici efattori sociali del potere imperiale da Augusto a Commodo (pp. 127-155). Pavia: IUSS Press.

Erikson, E. (2014). Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company, 1600–1757. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Märtl, C. (2021). Die Apostolische Kanzlei und der Romaufenthalt Friedrichs III. Romische Historische Mitteilungen, 133-154.

Meyer, A. (2016). The Curia: The Apostolic Chancery. In A. Larson, & K. Sisson, A Companion to the Medieval Papacy (pp. 239-258). Leiden: Brill.

Millar, F. (1977). The Emperor in the Roman World, 31 BC-AD 337. Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Effects of medium-sized opera festival on hotel sector in Finland, a differences-in-differences approach

Suominen, S.

Corresponding author – presenter

seppo.suominen@haaga-helia.fi Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences, Finland

Key words: opera festival, hotel sector

Background of the study

The outbreak of COVID-19 disease caused substantial damage to the whole world. The number of deaths increased and that led to vast cancellations of different events, including opera festivals allover the world. The Savonlinna opera festival which a longer history than hundred years had to be cancelled in 2020 and 2021. The festival takes place in July and usually the length of the festival is about one month.

The Savonlinna opera festival takes place every summer except when the COVID-19 pandemic led toa cancellation. While room rates differ across hotels and booking time, the events should on average have an increasing effect on hotel rates and revenues. The conventional measures in hotel management are revenue per available room (RevPAR), average daily rate (AvPri) = (room revenue)/(rooms sold) and occupancy percentage (CU%) = (rooms sold)/(rooms available) or simply demand/supply.

The festival has considerable effects on the Savonlinna region economy, both the restaurant business and hotel business flourish. Due to pandemia, two succeeding opera festivals were cancelled.

Savonlinna is so called summer city meaning that many Finns visit the city during the summertime from their summer cottages or during the opera festival. The city is livelier in summertime. The hotelcapacity doubles during the summer but the hotel room supply of good quality is far less than the number of seats in the opera festival venue. Hotel management can increase both average room price and capacity utilisation and therefore also revenue per available room (RevPAR) which is conventional measure in hotel business.

Hospitality management considers any event as demand generator. Hotels use both historical data and event calendar as well as airline data to make smart decisions concerning room rates. Any event, a large sports event or a large cultural event increases demand and hotel managers increase prices for the event period. Events and festivals are key elements for tourism and hospitality industry in many destinations (Getz & Page, 2014). Events can attract visitors who may not otherwise visit the area (Getz, 2010)

The positive effects of any local event and hotel revenue have been verified in several studies just to mention some, for example hotel occupancy percentage has been frequently used to measure events’ effects, usually positive economic benefits (Collins et al., 2022). Since hotel capacity is fixed in the short run and no new rooms are available, any large event increases hotel occupancy percentage andrevenue per available room (RevPAR). Cultural event visitors have higher incomes, highly educated and older (Mchone & Rungeling, 1999).

If new event is announced early enough, the hotel sector is able increase capacity, which is the case in Salamanca. The hotel sector in Salamanca, Spain got plenty of modernization of hotel facilities and new building partially due to Salamanca having chosen as a European Capital of Culture in 2002 (Herrero et al., 2006). Some events, like music festival seem have positive impact on cheaper category hotels measured by occupancy percentage while an endurance car racing event held at the Circuit of the Americas, Austin, USA had more positive impact on higher category hotels (Collins et al., 2022).

With Finnish data Tohmo (2005) showed that a rather tiny, local music festival had a larger positiveimpact on local tax revenues than the subsidy given by the municipality. There was no need to build any new facilities for the festival.

The spread of infectious disease in December 2019, COVID-19 is considered one the most challenged periods for hospitality industry. Lockdowns and mandatory quarantines were enforced in most countries that caused hospitality industry to collapse with an estimated 50 % decline in revenues (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021).

Aim of the study

The research question is to study the effects of an opera festival on the hotel industry in a small city, Savonlinna, in Finland. The purpose of this study is to have a look at hotel business statistics using a differences-in-differences method when the festival was cancelled.

The data covers nine cities and 140 months from January 2011 to August 2022. The estimation results show that all measures above mentioned increased in relation to other sample cities in Finland even when the opera festival was cancelled.

Methodology

The difference-in-difference method (DID) is a conventional method to estimate the impact of culturlevents on room prices. The method specifies the effects on room prices (𝑝𝑝𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖) during the event:

ln(𝑝𝑝𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖) = 𝛽𝛽0 + 𝛽𝛽1𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇 𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 + 𝛽𝛽2𝑃𝑃𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 + 𝛽𝛽3𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇 𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 ∙ 𝑃𝑃𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑇𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 + 𝑋𝑋𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑍𝑍

+ 𝑢𝑢𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 (1)

where ln (𝑝𝑝𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖) is the logarithm of the room price for hotel j and on day t by guest i. Treatment is a dummy variable (0/1) taking the value of 1 when for bookings at hotel that are affected by the sporting event and otherwise 0 (control hotels). Period (0/1) equals 1 during the event and otherwise0. Variables in 𝑋𝑋𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖𝑖 capture the effect of co-variates e.g. ground landings at Helsinki – Vantaa airport measuring the effects of COVID-19. The identification of the differences – in – differences method is outlined in table 1 below.

| Pre- intervention | Post-intervention | Time difference | |

| Treatment group | 𝛽𝛽0 +𝛽𝛽1 | 𝛽𝛽0 + 𝛽𝛽1 + 𝛽𝛽2 + 𝛽𝛽3 | 𝛽𝛽2 + 𝛽𝛽3 |

| Control group | 𝛽𝛽0 | 𝛽𝛽0 +𝛽𝛽2 | 𝛽𝛽2 |

| Group difference | 𝛽𝛽1 | 𝛽𝛽1 +𝛽𝛽3 | 𝛽𝛽3 |

Participating a cultural event has a role on travellers’ demand for hotel rooms that is captured by thevariables treatment and treatment period in model (1) above. The other relevant variables in the model (Z) are population of the city (z1) measuring business and leisure demand and ground landings (z2) inHelsinki-Vantaa (H-V) airport that is the largest international airport in Finland. During the sampleperiod from January 2011 to August 2022, the Covid-19 restrictions had a substantial effect on groundlandings – normally one to two million passengers per month but during the heaviest restrictions, there were about 20.000 passengers per month in the Helsinki-Vantaa airport. The ground landings variable thus measures both normal traveling demand and the effects of Covid-19. Since a large majority ofinternational passengers travel only to Helsinki region, the distance from Helsinki-Vantaa airport (z3) is one the co-variates used. Hence Z = (population of the city, ground landings per month in Helsinki-Vantaa airport, distance to Helsinki-Vantaa airport.

The monthly hotel data is from official statistics collected by Statistics Finland, as well as two control variables: Helsinki – Vantaa ground landings and population of the city. The distance to Helsinki – Vantaa airport is calculated by the author using distance maps.

The hotel performance variables, RevPAR, AvPri and CU are lower in Savonlinna than in other sample towns (t-test, equal variances not assumed, table 3).

| Savolinna, n = 140 | Other towns, n = 1120 | t-test | |

| RevPAR, € | 40.04 (20.68) | 54.95 (18.37) | 8.924*** |

| AvPri, € | 85.30 (18.97) | 95.26 (13.15) | 6.032*** |

| CU, % | 45.20 (11.71) | 56.82 (13.98) | 10.815*** |

Results

The results show that opera festival has had a substantial positive effect on RevPAR, ADR and CU%even when the opera festival was cancelled due to COVID-19 (July 2020 and July 2021). Since thehotel capacity in Savonlinna is rather small, opera festival goers book the hotel room well in advance to ensure the room and they did not withdraw the booking even when pandemia caused a cancellation of the festival.

The differences-in-differences method has not been used earlier to study the effects of festival cancellation in a medium-sized city hotel data in Finland. The results indicate that the hotel revenue statistics were improved even when the opera festival in Savonlinna was cancelled.

Since the festival venue capacity is 2264 seats and the summer-season hotel capacity is about 1200 rooms (off-season about 600 rooms), the scarcity of convenient hotel rooms is clear. Hotel managers take that into account and increase average prices, the hotel capacity is fully used.

The results are similar, if the treatment period is July 2020 (first cancellation) or July 2021 (second cancellation).

The capacity utilisation ratio (CU) usually is lower than in other sample cities (variable treatment in table 4) and that results in lower revenue per available room (RevPAR). The average price does not significantly differ from other sample city hotel room prices. The control variables are significant and reasonable except the effect of city population on RevPAR, the number of population increases average price but lowers capacity utilisation.

References

Collins, C., Depken, C. A., & Stephenson, E. F. (2022). The Impact of Sporting and Cultural Events in a Heterogeneous Hotel Market: Evidence from Austin, TX. Eastern Economic Journal, 48(4), 518–547. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-022-00220-3

Falk, M. (2017). Gains from horizontal collaboration among ski areas. Tourism Management, 60, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.008

Falk, M. T., & Vieru, M. (2021). Short-term hotel room price effects of sporting events. Tourism Economics, 27(3), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620901953

Getz, D. (2010). The nature and scope of festival studies. International Journal of Event Management Research, 5 (1), 1–47.

Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2014). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. In Tourism Management (Vol. 52, pp. 593–631). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.007

Giousmpasoglou, C., Marinakou, E., & Zopiatis, A. (2021). Hospitality managers in turbulent times: the COVID-19crisis. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), 1297–1318. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0741

Herrero, L. C., Sanz, J. Á., Devesa, M., Bedate, A., & del Barrio, M. J. (2006). The economic impact of culturalevents: A case-study of Salamanca 2002, European Capital of Culture. European Urban and Regional Studies, 13 (1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776406058946

Lechner, M., Rodriguez-Planas, N., & Fernández Kranz, D. (2016). Difference-in-difference estimation by FE and OLS when there is panel non-response. Journal of Applied Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2015.1126240

Matheson, V. A. (2009). Economic Multipliers and Mega-Event Analysis.: EBSCOhost. International Journal of Sport Finance. https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=65b53bd5-9d63-4a8d-8e4e- 5ebc1cff77ba%40redis

Mchone, W. W., & Rungeling, B. (1999). Rungeling) Hospitality Management. Hospitality Management, 18, 215–219.

Tohmo, T. (2005). Economic impacts of cultural events on local economies: an input-output analysis of the Kaustinen Folk Music Festival. In Tourism Economics (Vol. 11, Issue 3).

Zimbalist, A. (2016). The Organization and Economics of Sports Mega-Events. Intereconomics, 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-016-0586-y

Foreign women artists in Spain between 1914 and 1936 and the artistic and social revolution of Spanish women

Rodríguez Roldán, Rocío

rodrol5496@gmail.com

University of Seville, Spain

Keywords: Women artists; Spain; Avant-garde; Feminism; Art and Social revolution.

Background of the study and literature review

The present conference refers to our Doctoral Thesis which has been initiated during the academic year 2022/2023, being therefore in the process of development at present. This thesis is based, however, both on research previously carried out by the author, Rocío Rodríguez Roldán, and on artistic studies carried out mainly within the Spanish national sphere, being its starting hypothesis how the impact of the stays of foreign women artists as a consequence of the initiation of the World War First in Europe was more meaningful than it has been considered up until the current moment, influencing not only the Spanish artistic scene but also the social context, in which the aforementioned artists played a large role especially regarding to the consideration of the national women artists as professionals and not mere dilettanti in addition to the social revolution that led to the consecution of gender equality in Spain between the decades of 1920 and 1930.

The cited author’s research on the subject began in the research corresponding to her Bachelor’s Thesis-focusing on the Spanish artist Maruja Mallo (1902-1995)- and to her Master’s Thesis, a first approachto the general subject of the doctoral thesis, based on seven international women artists who settled in Spain between 1914 and 1936 and from whom we were able to provide new data. This research careerhas also continued through the collaboration with the Permanent

Observatory of Art and Gender1 since 2020 and with the work as a contracted researcher in the R+D+i research Project Female agency in the Andalusian art scene (1440-1940)2 -both affiliated with the University of Seville-, resulting in the participation in congresses and conferences -asspeaker, organizer and attendee- and in the publication of several research and scientific articles, specifically: “Maruja Mallo (1902-1995): Mujer y mujeres. Un universo creativo en femenino”3 in the scientific journal Eviterna, “Las Prisioneras. La mujer española bajo la mirada de MarieLaurencin” in Las mujeres en el sistema artístico, 1804-19394 (2023), “Carmen de Burgos y México: Colombine en la prensa mexicana desde 1900 hasta 1920” in Arte, identidad y cultura visual del siglo XIX en México5 (2023), “Marie Laurencin en Málaga (1915-1916): Los primeros pasos de la producción española” in “Quizá alguno de vuestros nombres logre un lugar en la historia” Mujeresen la escena artística andaluza (1440-1940)6 -pending publication- and “La peligrosa facilidad: Maroussia Valero (1892-1955)”7, part of a compendium of scientific research soon to be published by the University of Seville.

The aforementioned research works on which the present doctoral thesis is also based upon are being developed mainly during the present, among them Bajo el eclipse. Pintoras en España, 1880-19398(2019), Hacia poéticas de género. Mujeres artistas en España (1804-1939)9 (2022) and Las mujeres enel sistema artístico, 1804-193910 (2023). Other related research focuses on the study of individualartists, as well as other cultural, social and historical aspects, highlighting Pintoras en España, 1859-1926: de María Luisa de la Riva a Maruja Mallo 11(2014),La mujer y la pintura del XIX español. Cuatrocientas olvidadas y algunas más12 (2009), Mujer, modernismo y vanguardia en España (1898-1931)13 (2002) and Las modernas de Madrid: las grandes intelectuales españolas de la vanguardia14 (2001).

Aim, originality and novelty of the study

The fact that research on this topic -focusing mainly on national and not foreign artists, as in our case- is starting to be developed at present is a sign of its originality, which, added to its importance, has led us to choose it as the subject of our doctoral research with the following objectives: to deeply understand the social and artistic change that took place in Spain as a result of the establishment of foreign women artists on the occasion of the outbreak of the First World War, a phenomenon that initiated the adoption of avant-garde artistic languages in the country and about which, so far, only the impact of male artists has been taken into account; to carry out studies focused on women artists, often unknown at national and international level, in order to value their productions and histories; and to contribute to artistic gender studies, providing essential keys for the correct understanding of women artists and their works in their specific contexts. The latter is also intended to provide art institutions with instruments for the correct understanding and valorization of art created by women, which in turn would contribute to the dissemination of heritage and would affect not only the inhabitants of the different countries, but also the cultural tourism, as has been shown with exhibitions recently held in Spain on women artists as Hacia poéticas de género. Mujeresartistas en España: 1804-193915 (2022, IAACC Pablo Serrano, Zaragoza, and Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia) or Invitadas. Fragmentos sobre mujeres, ideología y artes plásticas en España (1833-1931)16 (2021, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid).

Methodology

In order to achieve the aforementioned objectives, we have determined the use of a methodology based on three different parts: the consultation and review of general and specific bibliographic sources, related to the artistic, historical and social context, as well as to the artists themselves working primarily within libraries, archives, databases, repositories and others in this and the following part; the search and analysis of newspaper and documentary sources, where magazines, newspapers, art catalogs and personal documents of each artist play a fundamental role not only in the process of analyzing their productions and impact, but also in the inquiry into how the foreign women artists were seen and treated by the mass media; and the location and study of the plastic work developed by the artists, mainly during their stay in Spain, exanimating for that purpose private and public collections of art. This methodology is being developed mainly within the Spanish national scope, although, due to the international character of the artists studied, in the future it will be necessary to include different international countries, among which France, the United States and different parts of Latin America stand out.

Results and argumentation

Through the use of this methodology and taking into account the objectives set out above, this doctoral research aims to obtain the following main results: the objective evaluation of the stays of various foreign women artists in Spain during the period between 1914 and 1936, determining not only the influence of the country on the creators, but also the influence exerted by them on the Spanish social and cultural panorama; the clarification of time periods which, regardless of their length, have usually been ignored in the individual studies of the artists carried out both in Spain and abroad, thus ignoring a part of the production of these women artists which this research intends to recover; the analysis of the impact of the stays of foreign women artists in the Spanish female creators of the time, influenced not only by the styles introduced in Spain by foreign artists, but also by the new conception of women artists, whose consideration would evolve from being considered “amateurs” to professional artists; and the recovery and valorization of art created by women artists, having an impact on the cultural scope by contributing to a better understanding of it and to the facilitation of scientific results that leads to a more objective treatment of the production of female creators, which at the same time will have an influence on both the social and economic spheres. We do not rule out the possibility that other main and secondary results may emerge in the course of the research.

Conclusion, managerial implications and limitations

We will conclude by reiterating the necessity to carry out this research within the artistic, historical and social field, not only because of the lack of studies focused on the subject, but also because of the need to continue carrying out gender studies that vindicate the role of women throughout history, often unjustly forgotten. The future results of this doctoral thesis will undoubtedly have a positive impact at the national and international level, contributing to a better knowledge and appreciation by scientific and artistic institutions and, ultimately, society, although we cannot ignore the main limitations to carry out the research: the need for both a large economic capital that allows travel to different cities and countries in order to locate the documentation and artistic works necessary for the study, and international cooperation to facilitate the study of the various women artists collected by our research.

1 “Observatorio Permanente de Arte y Género” in Spanish.

2 “Agencia femenina en la escena artística andaluza (1440-1940)” in Spanish.

3 “Maruja Mallo (1902-1995): Woman and women. A creative universe in feminine”.

4 “The Prisoners. Spanish women under the gaze of Marie Laurencin” in Women in the art system, 1804-1939.

5 “Carmen de Burgos and Mexico: Colombine in the Mexican press from 1900 to 1920” in Art, identity, and visual culture in the 19th century in Mexico.

6 “Marie Laurencin in Malaga (1915-1916): The first steps of Spanish production” in “Maybe one of your names will find a place in history” Women in the Andalusian art scene (1440-1940).

7 “Dangerous Ease: Maroussia Valero (1892-1955)”.

8 Under the eclipse. Women artists in Spain 1880-1939.

9 Towards poetics of gender. Women artists in Spain (1804-1939).

10 Women in the artistic system, 1804-1939.

11 Women Painters in Spain, 1859-1926: from María Luisa de la Riva to Maruja Mallo.

12 Women and painting in the Spanish 19th century. Four hundred forgotten women and some more.

13 Women, modernism, and avant-garde in Spain (1898-1931).

14 The modern women of Madrid: the great Spanish intellectuals of the avant-garde.

15 Towards poetics of gender. Women artists in Spain (1804-1939).

16 Guests. Fragments on women, ideology and plastic arts in Spain (1833-1931).

Referencies

De Diego, E. (2009). La mujer y la pintura del XIX español. Cuatrocientas olvidadas y algunas más. Ediciones Cátedra (Madrid).

Illán Martín, M., & Lomba, C. (Eds.). (2014). Pintoras en España, 1859-1926: de María Luisa de laRiva a Maruja Mallo. Vicerrectorado de Cultura y Política Social, Universidad de Zaragoza/ Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza.

Kirkpatrick, S. (2002). Mujer, modernismo y vanguardia en España (1898-1931). Ediciones Cátedra (Madrid).

Lomba Serrano, C. (2019). Bajo el eclipse. Pintoras en España, 1880-1939. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC).

Lomba Serrano, C., Alba Pagán, E., Castán Chocarro, A., & Illán Martín, M. (Eds.). (2023). Lasmujeres en el sistema artístico, 1804-1939. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza (PUZ).

Lomba Serrano, C., Brihuega, J., Gil, R., & Illán, M. (Eds.). (2021). Hacia poéticas de género. Mujeres artistas en España (1804- 1939). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza (PUZ).

Mangini, S. (2001). Las modernas de Madrid: las grandes intelectuales españolas de la vanguardia. Ediciones Península S.A. (Barcelona).

Rodríguez Roldán, R. (2021). Maruja Mallo (1902-1995): Mujer y Mujeres. Eviterna, 10, 184–197. https://doi.org/10.24310/eviternare.vi10.12531

Rodríguez Roldán, R. (2022). Las Prisioneras: la mujer española bajo la mirada de Marie Laurencin.In C. Lomba Serrano, E. Alba Pagán, A. Castán Chocarro, & M. Illán Martín (Eds.), Las mujeres en el sistema artístico, 1804-1939. (pp. 343–352). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza (PUZ).

Rodríguez Roldán, R. (2023). Carmen de Burgos y México: Colombine en la prensa mexicana desde1900 hasta 1920. In M. Illán Martín, I. Fraile Martín, & Benemérita Universidad de México(BUAP) (Eds.), Arte, identidad y cultura visual del siglo XIX en México (pp. 249–266). Editorial La Fuente (México). https://lafuente.buap.mx/content/arte- identidad-y-cultura-visual-del-siglo-xix-en-m%C3%A9xico

Rodríguez Roldán, R. (2023). Marie Laurencin en Málaga (1915-1916): Los primeros pasos de la producción española. In M. Illán Martín & A. Aranda Bernal (Eds.), “Quizá alguno de vuestros nombres logre un lugar en la historia”. Mujeres en la escena artística andaluza (1440-1940). (pp. 307–326). Sílex Ediciones (Madrid).

Model of integration of Fishing Tourism in the destination Tarifa (Spain). A sentiment analysis with face recognition and machine learning techniques

Toro-Sánchez, F.

Corresponding author – presenter

fennantoro@gmail.com

University of Seville, Spain. PhD. in Tourism

Keywords: fishing-tourism; sentiment analysis; facial expression analysis; Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction

Fishing Tourism is a modality of Rural tourism (Fleischer & Pizam, 1997) that has been developing for some years now with an outstanding interest in its promotion within the European Union due toits strong relationship with the objectives of Sustainable Tourism, both environmental and ecological. It can also be framed within recreational and adventure tourism as well as having a high cultural value.

The definition of the content of the tourist attraction and the objectives of sustainability (Bramwell & Lane, 1993) must define the tourist offer in such a way as to promote the preservation of the natural habitat and the promotion of local development together with the expression of the cultural values and traditions of the seafaring community in such a way that the visitor-tourist can enjoy their knowledge and experience. Fishing and aquaculture are human activities that have a significant role in the long-term conservation and sustainable use of the world’s oceans and their resources and are therefore integral to the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) FAO (Hall, 2021).

Literature Review

The Fishing Tourism Activity

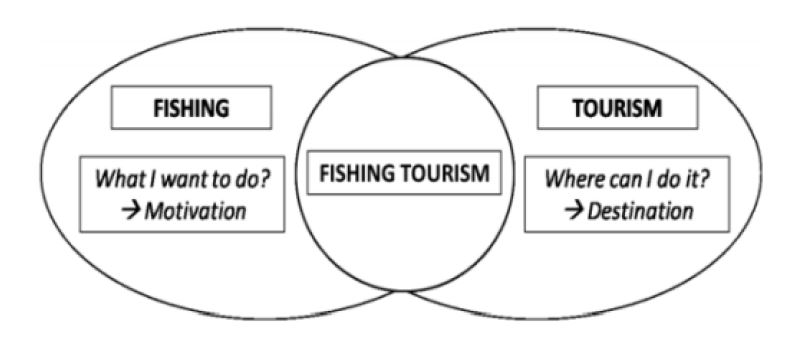

The development of the activity of fishing tourism is consequently linked to the terms used in the definition (Alias et al., 2014), although it is clear that this development is slow, despite the fact that it is a powerful instrument for promoting the local economy and providing added value to the fishing industry (Holmgren, 2012). The promotion of this activity is not homogeneous (Muñoz, 2018) although in Europe, in certain countries, a more incipient development can be observed in the movement of tourists and the development of agreements around these activities.(Vasconcelos et al., 2014), initially developed by the so-called MARIMED (Romarís, 2016), which promotes fishing tourism as a focus for the central development of a specific local nucleus, considering its innovative factor within a social, economic and cultural framework and configuring itself as a tool that contributes to the sustainability of the marine environment (Pérez Piernas & Espejo Marín, 2012). Other models conceive the suitability of a tourist destination already consolidated or in an advanced stage of development, in such a way that a specific fishing tourism activity is promoted and its development is parallel to that of the tourist destination where it is located (Cheong, 2003). This allows the main interest of the destination, as expressed by the tourist, such asthe sun and beach holiday, to be combined with the interests of the local coastal economy (Tsafoutis & Metaxas, 2021). Recreational here takes a leading role that drives the instinct of the activity (Ditton et al., 2002; Komppula & Gartner, 2013; Zwirn et al., 2005, 2005) so that the tourist fishing activity does not solely define the tourist interest of the destination (Laiho et al., 2005). Fishing Tourism thus combines two independent but complementary concepts: fishing on the one hand and tourism on the other. The balance of both variables and the different factors that indicate them (Grigoroudis & Siskos, 2002) can favour the solution to the development model of a specific Fishing Tourism activity (Lari et al., 2019).

Figure 1: Fisheries Tourism and Destination Development Model (Lari et al., 2019)

Face recognition sensitive

In this section we want to address a framework of developments on the methodology of facial expression analysis (Diamantini et al., 2021) supported in the video format that lead to results that can be used for user sentiment analysis studies (Saura et al., 2019). Human emotions can be classified into an archetype that includes six specific types, each of which corresponds to a specific type offacial expression that is not related to specific characteristics of the user’s gender, age, or ethnicity (Diamantini et al., 2021).

This classification of feelings is based on Ekman’s theory (Ekman, 1992), the most widespread in thestudy of emotion recognition analysis (Diamantini et al., 2021) classifying them into the following six: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.

An aspect of this methodology is to consider the facial modifications that cause the expression of feelings (Perikos et al., 2018)and the compilation of large databases to generalise these attitudes(Sun et al., 2004; Sun & Jin, 2018). Two variants of the applied methods exist: on the one hand, the intensity with which the facial expression changes during a time phase is analysed, which is calledHilbert-Huang Transform -HHT- (Soleymani et al., 2015), and on the other hand, what is analysed are the different sequence-by-sequence shots of a given video recording, which is called Hidden Markov Models -HMMs- (Mo et al., 2018).

Sentiment analysis combines data mining with Natural Language Processing (Jayalekshmi &Mathew, 2017) and when it comes to image-based analysis, the complication is offered by the technology used which involves image segmentation, image extraction and verification in relation to the analysed sentiments (Hjelmås & Low, 2001).

This information can be generated in two basic ways from the video and further data processing:

- Image processing through pixels, where the consistency of the different parts of the face figure is sought, known as the Viola-Jones algorithm.(Jayalekshmi & Mathew, 2017; Jensen, 2008; Wang, 2014)

- Image processing through detection of points within the face and action units as vectors linking different of these selected points and measuring the different distances related to the different registered expressions -vectors- and the correlations between them. (Baltrusaitis & Morency, 2018; Busso & Narayanan, 2007; Reisenzein & Horstmann, 2013).

It is this second strand of image-as-data processing that underpins the System Theory of Facial Action Coding.-FACS, Facial Action Coding System- (Diamantini et al., 2021).

Aim to study

This study uses a qualitative study based on an analysis of the user’s feelings and, specifically, on facial recognition of expressions to determine feelings, complemented by a study with machine learning techniques where the presence of different feelings and their intensity is observed within the study.

Methodology

For the purpose of this study focused on the analysis of user sentiment, expression recognition is employed through the observation of a video. Specifically, FACS coding is applied, which consists of the following phases (Baltrusaitis. T & Morency, 2018):

- Initial performance in three classes of sentiment analysis: negative-neutral and positive,

- Partitioning of the video into different parts, which allows for a better evaluation of thesentiments,

- Processing of frames in a way that targets identified by each of the sentiments to be analysed are fixed. This is a supervised analysis.

- Sentiment recognition; the expression reflected on the user’s face is associated with the reactions recorded in each of the analysed frames. The intensity of each parameter in the form of a sentiment is evaluated on a percentage scale by taking an average of all the components of the sample.

For this purpose, the Feeder software (https://getfeeder.com/) is used, which compiles the aforementioned methodological steps and whose algorithm translates each of the emotions felt by your audience (fear, anger, joy, sadness, contempt, disgust and surprise) into pure qualitative metrics aimed at understanding what is really happening in the viewing of the video.

Results and Findings

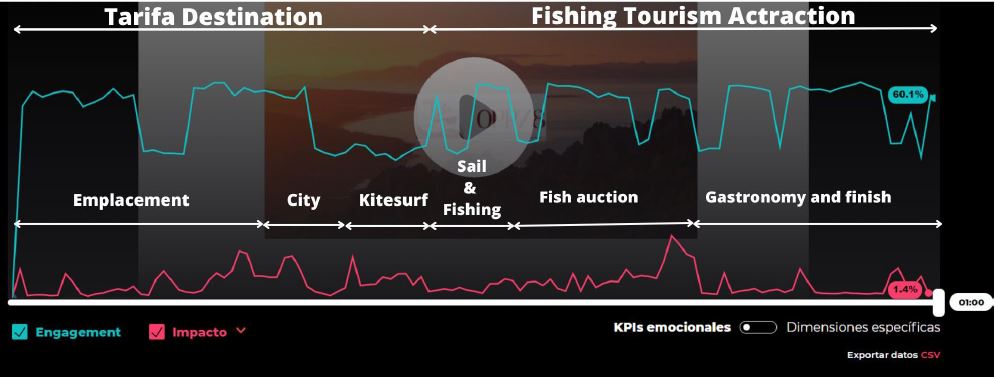

The sample of this qualitative study contains one hundred people from the geographical area of the Spanish territory and who speak Spanish. They were treated to a one-minute video presenting the theme of Fishing Tourism in the town of Tarifa (Spain). Specifically, the video (https://my.getfeeder.com/campaign/pescaturismotarifa) is structured in two very distinct sections which are then divided into different sub-sections:

Destination Presentation Tarifa (0-27 seconds)

- Location (0-16 seconds)

- Urban environment (16-20 seconds)

- Kitesurfing activity (21-27 seconds)

Presentation of the activity Atun Rojo/ Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus) Fishing Tourism: (28-60 seconds)

- Navigation and fishing (28-39 seconds.)

- Processing of catches at the fish market (40-50 seconds.)

- Tuna trolling, gastronomy and final (50-60 seconds.)

Figure 2: Ratio of engagement and impact of the target video. Source: Own elaboration.

A first division is observed between the part where the destination is shown and the part that shows the tourist attraction itself, in two basic general and basic dimensions, which are commitment and impact. It is observed that the first part of the location presents parts where the commitment of the viewer is declining in a way that identifies the same destination although not uniformly, there is a growth of this commitment when at the end of this part observes the presence of people practising the activity of kitesurfing, with which the tourist destination of Tarifa is identified. The second part of the video, with the concrete exhibition of the tourist attraction of fishing tourism, offers a higher level of engagement and attention, especially in the part where the navigation and the catching of tuna on the boat are shown. However, the commitment drops at a specific point where the animal is shown already dead and treated at the fish market and where the processing work for its commercialisation is observed.

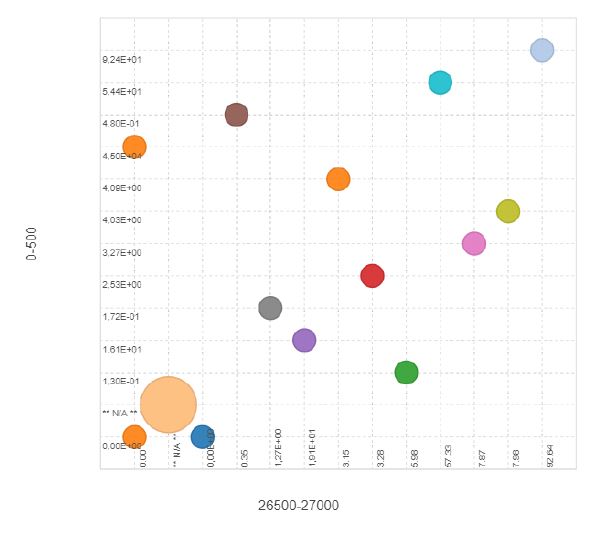

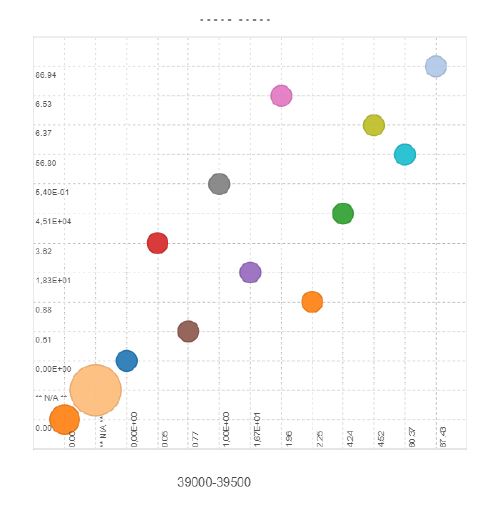

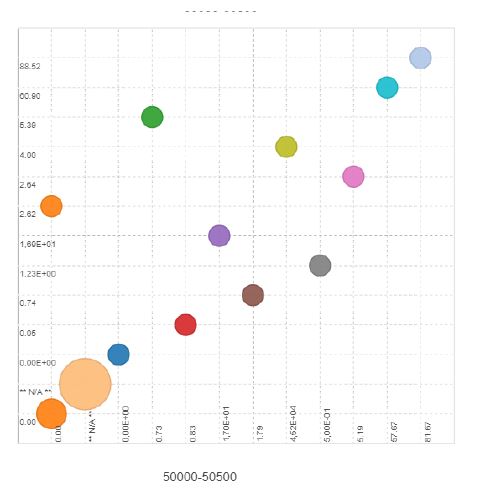

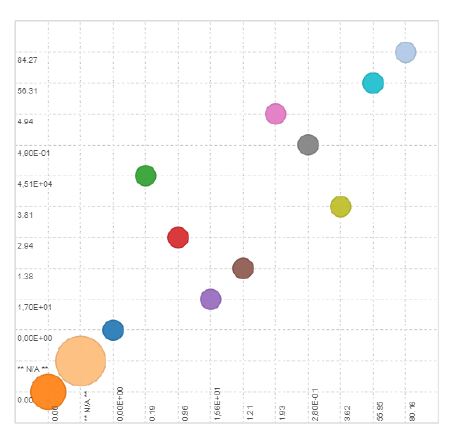

The data is processed through Machine Learning and in concrete terms the Big ML software (https://bigml.com/) is used where the different dimensions of general and specific sentiment are represented by different coloured spheres:

For the comparative study of the different video sequences, Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) is used (Hair et al., 2019) is a similar technique for identifying those attributes of variables that areidentified within a study. As a result of the sphere appearing in the top right- hand corner, the variable’s relevance in the study is clear.

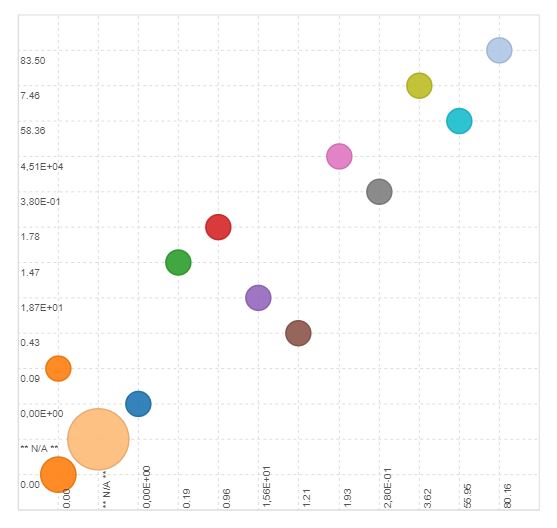

Figure 3: Sentiment ratio at tourist destination Tarifa: 0 to 27 seconds Source: Own elaboration.

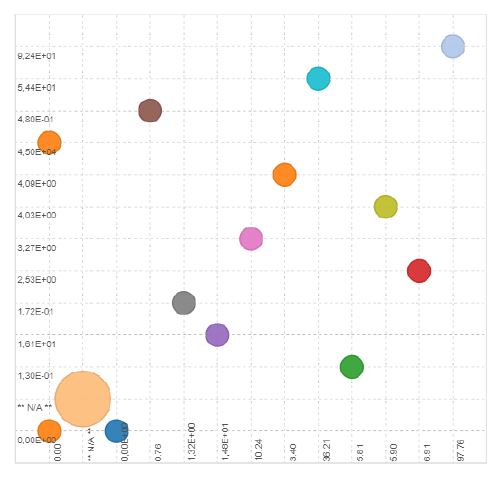

Figure 4: Ratio of feelings in activity Fisheries Tourism: 27 to 60 seconds Source: Own elaboration.

Figures 2 and 3 show the relationship between the variables analysed in the two general parts of the video study. Among all of them, we follow the behaviour of the red sphere that shows disapproval as a feeling. It can be seen that if in general the first part of the destination shows a certain disapproval, within neutral values, in the part that shows the activity, the disapproval of what the user visualises reaches a certain importance. Both user attention and validation as feelings are maintained at high values, which confirms the rest of the feelings analysed.

Figure 5: Sentiment Ratio in Localisation: 0 to 16 seconds Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 6: Sentiment Ratio in Urban Environment: 16 to 20 seconds Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 7 : Ratio of feelings in Kite Surfing Activity : 20 to 27 seconds Source: Own elaboration.

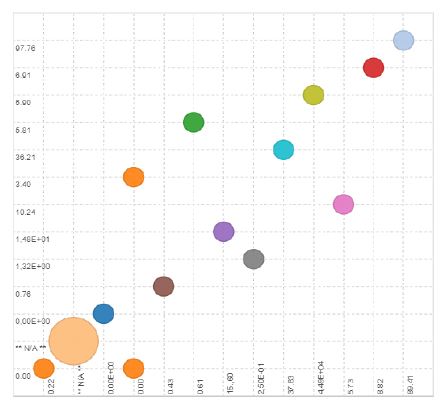

Figure 8: Sentiment ratio in Navigation and Fishing: 28 to 39 seconds.

Source: Own elaboration

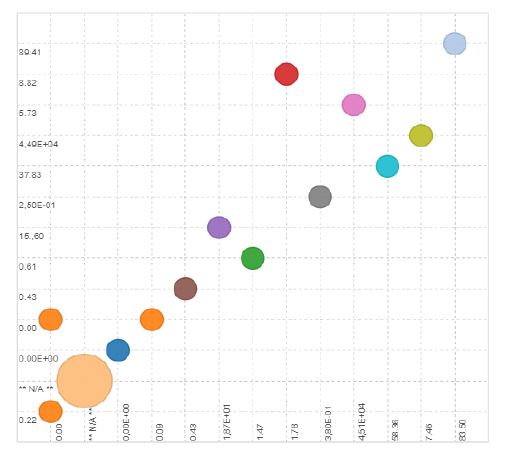

Figure 9: Ratio of feelings in fish market: 40 to 50 seconds.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 10: Fish-banked and gastronomy sentiment ratio: 50 to 60 seconds.

Source: Own elaboration.

Following the analysis of the fragments of the video with more specific content, we observe case bycase the importance and relevance of each variable, although we maintain our intention to analyse only the variable of disapproval, which we can say is presented in neutral values except when the part of the streets of the city is shown and at the beginning of the part that shows the kite surfing activity: in both sequences there is no presence of people in the images shown.

Conclusions

The sentiment analysis opens up new possibilities for facilitating and complementing decision- making in the field of marketing and specifically in the definition of product and service offerings. In this case, it helps to define the positioning of a specific tourism task within the global offer of a specific destination, which can provide a glimpse of the favourable alignment of tasks to integrate the appropriate development model, specifically in the studied case of tourism fishing.

The perspective from the user is presumed to be a factor that complements the adoption of a tourism development model together with other factors that constitute the objectives of sustainability coupled with the attractiveness that the activity should contain.

In this case, it can be seen how the identification of the destination with the attributes identified by theuser helps a more unfamiliar activity to be integrated into the acceptance of the tourism offer and the attraction for the user to carry it out.

References

Alias, M. A., Ahmad, N. A., Ahmad, M. A., & Safri, F. M. (2014). Sustainable approach of fishing tourism in Kenyir Lake. Hospitality and Tourism, 3.

Baltrusaitis. T, Y. C. L., A. Zadeh, & Morency, L.-P. (2018). Openface 2.0: Facial behaviour analysis toolkit”, IEEE. International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition, 59-66,.

Bauer, J., & Herr, A. (2004). Hunting and Fishing tourism. Wildlife Tourism: Impacts, Management and Planning; Common Ground Publishing, apter 4, 57-77.

Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (1993). Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 1-5.

Busso, D, & Narayanan, S. (2007). Interrelation between speech and facial gestures in emotionalutterances: A single subject study”, Audio Speech and Language Processing. IEEE Transactions, 15, 2331-2347,.

Cheong, S. M. (2003). Privatizing tendencies: Fishing communities and tourism in Korea. Marine Policy, 27(1), 23-29.

Diamantini, C., Mircoli, A., Potena, D., & Storti, E. (2021). Automatic annotation of corpora for emotion recognition through facial expressions analysis. 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR, 5650-5657.

Ditton, R. B., Holland, S. M., & Anderson, D. K. (2002). Recreational Fishing as Tourism. Fisheries, 27, 17-24.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6(3-4), 169-200.Fleischer, A., & Pizam, A. (1997). Rural tourism in Israel. Tourism management, 18(6), 367-372.

Grigoroudis, E., & Siskos, Y. (2002). Preference disaggregation for measuring and analysingcustomer satisfaction: The MUSA method. European Journal of Operational Research, 143(1), 148-170.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Castillo Apraiz, J., Cepeda Carrión, G., & Roldán, J. L. (2019). Manual de partial least squares structural equation modeling (pls-sem. OmniaScience Scholar.

Hall, C. M. (2021). Tourism and fishing. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(4), 361-373,. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1955739

Hjelmås, E., & Low, B. K. (2001). Face detection: A survey. Computer Vision and ImageUnderstanding, 83(3), 236-274.

Holmgren, H. (2012). Innovation in nature-based tourism: The case of marine fishing tourism in Northern Norway. En Destination branding heritage and authenticity (pp. 394-418).

Jayalekshmi, J.,& Mathew, T. (2017). Facial expression recognition and emotion classification system for sentiment analysis. 2017 International Conference on Networks & Advances in Computational Technologies (NetACT) (Pp, 1-8.

Jensen, O. H. (2008). Implementing the Viola-Jones face detection algorithm“. Diss. TechnicalUniversity of Denmark, DTU, DK-2800 Kgs.

Komppula, R., & Gartner, W. C. (2013). Hunting as a travel experience: An auto-ethnographic study of hunting tourism in Finland and the USA. Tourism Management, 35, 168-180.

Laiho, M., Herranen, V., Kivi, E., Laiho, M., Herranen, V., & Kivi, E. K. N. (2005).Kehittämishaasteet ja Hanketoiminta Suomessa; Maa- ja Metsätalousministeriön Julkaisuja 3/2005; Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy (p. 69).

Lari, T., Komppula, R., & Pesonen, J. (2019). Fishing as a Tourist Experience Case: FinnishRecreational Fishermen [Master’s Thesis,]. University of Eastern Finland Faculty of Social Sciences and Business Studies.

Mo, S., Niu, J., Su, Y., & Das, S. K. (2018). A novel feature set for video emotion recognition. Neurocomputing, 291, 11-20.

Muñoz, D. M. (2018). Contribution to the concepts of fishing tourism and pesca-tourism. Cuadernos de Turismo, 42, 655.

Pérez Piernas, P., & Espejo Marín, C. (2012). Fishing as a factor promoting sustainable touristdevelopment in Águilas, Murcia (Spain. Cuadernos de Turismo, 30, 267-329.

Perikos, I., Paraskevas, M., & Hatzilygeroudis, I. (2018). Facial expression recognition usingadaptive neuro-fuzzy inference. Systems”, 2018 IEEE/ACIS 17th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS, 1-6,.

Reisenzein, R, M. S., & Horstmann, G. (2013). Coherence between emotion and facial expression.Evidence from Laboratory Experiments”, Emotion Review, 5(1), 16-23,.

Romarís, C. A. P. (2016). El turismo marinero: Un producto diferenciador y emergente de la oferta turística del litoral gallego. En X CITURDES: Congreso Internacional de Turismo Rural y Desarrollo Sostenible (pp. 401-410).

Saura, J. R., Debasa, F., & Reyes-Menendez, A. (2019). Does user generated content characterizemillennials’ generation behavior? Discussing the relation between sns and open innovation.Journal of.

Soleymani, M., Asghari-Esfeden, S., Fu, Y., & Pantic, M. (2015). Analysis of EEG signals and facial expressions for continuous emotion detection. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing,7(1), 17-28.

Sun, N. S., Lew, M., & Gevers, T. (2004). Authentic emotion detection in real-time video”,Proceedings of the. En International Workshop on Computer Vision in Human-Computer Interaction (CVHCI (pp. 94-104,).

Sun W, H. Z., & Jin, Z. (2018). A complementary facial representation extracting method based on deep learning”, Neurocomputing (Vol. 306, pp. 246-259,).

Tsafoutis, D., & Metaxas, T. (2021). Fishing Tourism in Greece: Defining Possibilities and Prospects.Sustainability, 13(24), 13847.

Vasconcelos, V., Sousa, R., & Santos, A. (2014). Artesanato local e atividade pesqueira nacomunidade do Carnaubal (Luís Correira, Piauí-Brasil) como fatores para odesenvolvimento sustentável do turismo.

Wang, Y. Q. (2014). An analysis of the Viola-Jones face detection algorithm. Image Processing On Line, 4, 128-148.

Zwirn, M., Pinski, M., & Rahr, G. (2005). Angling ecotourism: Issues, guidelines and experiences from Kamchatka. J. Ecotourism, 4, 16-31.

Role of the Intangible Cultural Heritage recognized by UNESCO as a Regenerative Tourism resource.

Case study: Nowruz, the Persian new year celebrations.

Dezfoulian, Dorsa

dordez@alum.us.es

University of Sevilla, Spain

Keywords: Intangible Cultural Heritage; Iran; Nowruz; UNESCO; Regenerative Tourism.

Background of the study/literature review

1. Intangible cultural heritage (ICH)

What could be understood as intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is defined by UNESCO itself in 2003 as “the actions, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills, as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces that are inherent to them and that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals consider to be parts of their cultural heritage” (UNESCO, Document on the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2003).

Therefore, understanding the intangible cultural heritage of different countries helps countries’ intercultural dialoguesand encourages them to have mutual respect for other ways of life. ICH familiarizes people with identity and continuity of life, and respect for cultural diversity, freedom, and independence triggers human creativity (Mirvahedi & Ghaediha, 2020).

2. Regenerative tourism

Tourism systems are considered inseparable from nature and are obliged to respect the principles and laws of the Earth. Regenerative tourism is a niche type that follows the “Regenerative Economy” idea. The concept works on the principle in which conditions are provided for the industry to be reborn, continuously renewed, and transcended into anew form without much human interposition (Hussain, 2021).

With this idea, we want to continue to damage less and tend to rebuild everything that has been destroyed before. Somehow following the main idea of sustainable tourism with more responsibility. Regenerative tourism has not yet been a phenomenon in Iran, but following sustainable tourism, many efforts have been made; from setting standards for accommodations to accepting tour groups of fewer people, and teaching visitors how to act in the region of the locals to respect their beliefs and traditions. In this way, as we move into the world of regenerative tourism, we could move towards alternative ways of responding to mass tourism that benefits both the demand (visitors) and the supply (locals).

3. ICH of Iran

Iran is one of the countries in the Asia Minor region, where rituals and traditions have accompanied its society for centuries and even millennia (Beheshti, 2020). Following Iran’s current policies, laws, and conditions, one of thepossible ways to develop the country’s tourism industry would be through cultural tourism. Hence, the possibility thatIran’s intangible heritage might offer, is to be explored further.

The possibility of becoming an attractive tourist resource for the national and international market would be one of the points to be considered to place it on the map of the inbound tourism sector, although this is probably still far from being achieved. In this way, the visitor would perhaps cease to be a mere passive tourist and become an active tourist, where the use of traditions would allow a link between the citizen of the destination and the visitor, approaching it most responsibly and respectfully as possible and not losing the identity essence of the area where this activity takes place.

Table 1: Intangible Resources declared as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO

| Domain | Intangible cultural heritage | Registration year |

|---|---|---|

| Oral traditions and expressions | Naqqali, Iranian dramatic narrative | 2011 |

| Performing arts | Radif of Iranian music | 2009 |

| Music of the Bakhshis from Khorasan | 2010 | |

| The art of crafting and playing Kamancheh | 2017 | |

| Traditional skills of making and playing Dotar | 2019 | |

| Art of miniature | 2020 | |

| National program to safeguard the traditional art of calligraphy in Iran | 2021 | |

| Creation and performance of the Oud | 2022 | |

| Social practices, rituals, and festive events | Pahlevani and Zoorkhanei Rituals | 2010 |

| Ta’ziye Ritual Dramatic Art | 2010 | |

| The Qalishuyan Mashhad e Ardehal Rituals | 2012 | |

| Nowruz | 2016 | |

| Chogan, a horse riding game | 2017 | |

| Pilgrimage to the Monastery of St. Thaddeus Apostle | 2020 | |

| Yaldā/Chella | 2022 | |

| Traditional crafts | Traditional carpet weaving techniques in Kashan | 2010 |

| Traditional carpet weaving techniques in Fars | 2010 | |

| Traditional Iranian Lenj shipbuilding and navigation skills in the Persian Gulf | 2011 | |

| The art of Turkmen style embroidery | 2022 | |

| Sericulture and traditional weaving silk production | 2022 | |

| Knowledge and practices related to nature and the universe | Flatbread making and the culture of sharing: Lavash | 2016 |

4. Nowruz, celebrations of the Persian new year

The meaning of “Nowruz” translated from Persian is “New Day” which marks the beginning of the new year in the calendar and coincides with the date of the astronomical vernal equinox which lies on 20 or 21 of March.

The New Year in Iran and neighboring countries and nationalities that celebrate it is a historical, ancient ceremony with a religious component to it. It is linked to the heart and soul of the people who celebrate it every year (Behzadi, 2016). Nowruz is a set of rituals that range from private ceremonies (what is performed at home) to more public ceremonies and group dances. The fact that people from 12 different countries share the culture to celebrate Nowruz doubles the importance of this ancient custom in the world (Behzadi Manesh, 2021). In this sense, this great event can be studied from different perspectives in terms of its origin, how it was celebrated, traditions, etc. according to UNESCO on the official page of Nowruz registered on the ICH list “These practices support cultural diversity and tolerance and contribute to building community solidarity and peace”.

As Azkaei points out in 1974, one of the first books that collected the history of Nowruz through the dynasties of Iran, called “History and Reference of Nowruz”, also in “Nowruz: the celebration of the Rebirth of Creation” the author, Bulookbashi, analyzed for the first time the different origins of this celebration, its traditions, as well as the days before and after these celebrations until the thirteenth day (Bulookbashi, 2010). Similarly, Bashiri analyzed the origin of the current calendar used in Iran, which begins on the first day of spring and is celebrated as Nowruz. The calendar was one of the great inventions of Hakim Omar Khayyam during the Seljuk empire in Iran and is still in use today. In his work, “Nowruz Nameh”, Khayyam first discusses the formation of Nowruz and what customs were popular inNowruz during the time of different kings. He also described the gifts of Nowruz and what was common in the court of kings (Bashiri, 2016).

In 2019 a corrected version of “Nowruz Nameh” was published, based on the unique edition of the Berlin Public Library, on all dimensions of this celebration by Mojtaba Minavi called “Nowruz Nameh: A Treatise on the Origin, History, and Customs of the Nowruz celebration” (Minavi, 2019).

“As it contributes to cultural diversity and friendship among peoples and different communities, Nowruz fits closelywith UNESCO’s mandate” (UNESCO, International Day of Nowruz, 2023). UNESCO (2023) also claims that the UN general assembly welcomes every effort to raise awareness about Nowruz and its traditions, like annual events, etc.

Aim of the study

The main objective of the research is to analyze the possibilities of interrelation between the concepts of Regenerative Tourism” and “Intangible Cultural Heritage”, as well as to approach their possibilities in a concrete case, the Nowruz. These days, despite the political conditions of the country, the officials of this sector and the leader of Iran emphasize more on the development of Iran’s tourism by using the rich culture. We know that one of the main purposes of tourism is to be used as a diplomacy of peace between different cultures and nations (Haulot, 1983). New Year celebrations offer a great opportunity to experience a different culture and its unique traditions and rituals. While Nowruz may be known to some, its specific ceremonies remain unfamiliar to many.

Linking ICH with one of the most recent trends in the industry of tourism, regenerative tourism, may not only help keep Iran’s tourism updated but, might be a new way of safeguarding the precious Intangible Heritage for us and the future.

Methodology

The literature review is based on the most recent studies done on the issues of ICH, Regenerative Tourism, and the Nowruz festive event.

In this paper, we focus on a literature review and exploratory approach to the tourism potential of Nowruz through a small survey of residents.